By DAVID MYTON

Europe in the mid-18th Century was a continent on the cusp of momentous change. The French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, the demographic shift of country folk migrating to the cities, for example, were simmering but not yet boiling.

In England, changes were coming, but slowly enough for people to assume that for the current and future generations nothing much would be different from the present.

“Change has not yet reached that point at which it is assumed that the horizons of each successive generation will be different,” writes renowned historian E.P. Thompson in Customs In Common.

In the 18th century, custom – the traditional way of doing things - was “the rhetoric of legitimation for almost any usage, practice, or demanded right,” Thompson writes.

He defines Culture as a “system of shared meanings, attitudes and values, and the symbolic forms (such as performances and artefacts) in which they are embodied”.

The culture of England’s common people had developed “in opposition to the constraints and controls of the patrician rulers”, and was located within a “working environment of exploitation, of relations of power which are masked by the rituals of paternalism and deference”.

Central to this culture was a history of “ritualised or stylised performances” which were designed to be “powerful self-motivating forces of social and moral regulation” against “intolerable deviant behaviour”.

Such behaviour transgressed a community’s “inherited expectations as to approved marital roles and sexual conduct”.

These norms were not identical to those proclaimed by the Church or Society’s rulers … they were “defined within the plebeian culture itself”.

And so, for example, the same shaming rituals which were used against a “notorious sexual offender” could also be used against the squire and his gamekeepers, or excise officers, who in various ways may have exploited the community.

The rituals came from a “conservative culture” which appealed to, and sought to reinforce, traditional usages.

They are “non-rational”, says Thompson, in that they do not appeal to reason through the book, pamphlet or sermon and “they impose the sanctions of force, ridicule, shame, intimidation”.

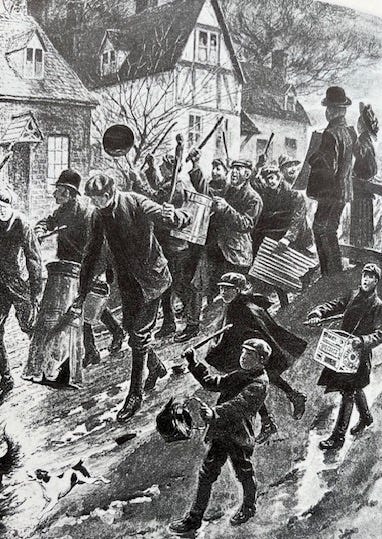

Let’s just look at one of them: Rough Music

The term Rough Music had been generally used in England since the end of the 17th century “to denote a rude cacophony, with or without more elaborate ritual, which usually directed mockery or hostility against individuals who offended against certain community norms”.

It resembled charivari in France, the Italian scampanate, and to several German customs. In parts of the US it was known as shivaree.

Within Britain, Rough Music generally was a ritual in which “certain basic human properties can be found: raucus, ear-shattering noise, unpitying laughter, and the mimicking of obscenities”.

The noise formed part of a ritualised expression of hostility. It was supported “by the din of cleavers, tongs, tambourines, kits, humstrums, serpents, ram’s horns and other historical kinds of music.

In other cases the ritual could be elaborate, and might include the riding of the victim (or a proxy) on a pole or donkey; masking and dancing; elaborate recitatives; rough mime or street drama on a cart or platform; or, frequently, the parading and burning of effigies.

In Britain, writes Thompson, the rituals extended across the spectrum from the good-humoured chaffing of the newly-wed to satire of the greatest brutality.

“It is possible to detect in almost every 18th century crowd action some legitimising notion … men and women in the crowd were informed by the belief that they were defending traditional rights or customs [and] in general, they were supported by the wider consensus of the community.”

REFERENCES

E.P. Thompson, Customs In Common, Penguin Books, 1993

E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, Gollancz, London, 1963