Arthur and Martha: their hopes and dreams were shattered by the war that never ended

How the Great War's impact ripples out more than 100 years after the event

By DAVID MYTON

My paternal grandfather, Arthur, was among the first cab drivers in his home city of York, England, to buy and own a motorized taxi sometime in 1914.

The switch from horse and buggy to a new-fangled motorcar was an exciting and potentially profitable move for Arthur. Thanks to lots of hard work his cab business had been growing; now it should grow some more.

But then, as World War 1 dragged on and the fighting intensified, Arthur was called up to serve in the Royal Artillery somewhere on the Western Front.

His life, his hopes and dreams, his plans and prospects, were shattered for ever when he was caught in a German gas attack. His lungs wrecked, Arthur returned to civilian life a sick man.

He never drove a taxi again and struggled to survive and to support his family on meagre government benefits. He died in his early 60s, a sad, broke and disillusioned man.

My Grandmother, Martha, suffered too. Permanently exhausted, her nerves shot to pieces, she worked to make ends meet while looking after Arthur and a couple of young kids. She died a few years after Arthur passed away.

The kids had to leave school as early as possible. With no decent education, they were forced into menial, low-paid jobs. Then in 1939, as a direct consequence of World War 1, another war erupted. My father was called-up at the age of 18 to serve in the British 14th Army in the war against Japan. He wasn’t physically wounded, but nevertheless he suffered the permanent after-effects of several tropical diseases that blighted his life.

Turning points and consequences

The Great War’s impact ripples out in subtle ways more than 100 years after the event.

It’s there, residing in individuals, families and communities whose potential may have been shattered; and conversely in those who have prospered.

There’s nothing we can do about it, there’s no point in complaining about it, but it is tempting now and again to think about what might have been had not their lives been blighted by war.

History is replete with “what ifs”.

What if Franz Ferdinand hadn’t taken a wrong turn in the streets of Sarajevo?

What if Alfred von Schlieffen had thought - “you know what, violating Belgian neutrality is going to cause more trouble than it’s worth”?

Or if Arthur’s artillery company had been diverted elsewhere on the morning of the fateful gas attack? Nobody knows.

When it comes to history, we know what happens next. The people of the time had no idea. Even when they tried to prepare themselves for the future, the law of unintended consequences would often have the last laugh.

Most egregiously, the people of the present so often read back their own morals, prejudices and knowledge into bygone behaviours – as if history’s people are just us in fancy dress and ought to be judged with fearless harshness if we don’t like the way they behave or the decisions they make.

There is no shortage of opinion and criticism when it comes to the 20th century’s two mega wars.

The outstanding scholar of World War 1, Professor Margaret MacMillan, says it is estimated that some 32,000 books in English have been published just on the origins of the Great War. That’s 32,000 opinions, angles, agendas and viewpoints.

Our views of World War 1 have also been shaped by poets, supremely Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Isaac Rosenberg, Edmund Blunden and the unfairly-derided Rupert Brooke.

Then let’s throw in some opinion-shaping fiction such as Oh What A Lovely War, Birdsong, War Horse, Parade’s End, and the German Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet On The Western Front.

And we must not forget the 1989 television show Blackadder Goes Forth featuring Baldrick, General Melchett and Lieutenant George St Barleigh. It’s funny, brilliantly acted, well directed and scripted – but what it isn’t is history

.

Frames of reference: experiencing reality

Politician and author Alan Clark delivered a phrase that stuck when in 1961 he opined that the British Army of 1914-18 had consisted of “lions led by donkeys”.

It’s easy to make such judgments, but they ignore what the scholars Sonke Neitzel and Harald Welzer refer to as “frames of reference” – that is, the way reality is experienced and understood by the people of history.

“When we want to explain human behavior, we first must reconstruct the frame of reference in which given human beings operated, including which factors structured their perception and suggested certain conclusions,” they write.

“When frames of reference are ignored, academic analysis of past actions automatically become normative, since present-day standards are enlisted to allow us to understand what was going on. Analysing frames of reference allow us to view that violence of [war] in non-moral, non-normative fashion.”

My early views of World War 1 were shaped by Captain W E Johns’s hero pilot Biggles and his adventures in a Sopwith Camel aeroplane. I thought it was brilliant (I was very young).

At the age of 16 I read Wilfred Owen et al for school exams. I had never encountered more beautiful and moving poems than Strange Meeting and Dulce Et Decorum Est. They remain wonderful and moving poems.

Here’s a few lines from Strange Meeting:

I went hunting wild

After the wildest beauty in the world,

Which lies not calm in eyes, or braided hair,

But mocks the steady running of the hour,

And if it grieves, grieves richlier than here.

For by my glee might many men have laughed,

And of my weeping something had been left,

Which must die now. I mean the truth untold,

The pity of war, the pity war distilled.

Now men will go content with what we spoiled.

Or, discontent, boil bloody, and be spilled.

They will be swift with swiftness of the tigress.

And then there’s the writer Rudyard Kipling whose words from Ecclesiasticus in the King James Version of The Bible - “Their name liveth for ever more (via Deuteronomy) - still adorn war memorials, as does the phrase Lest We Forget.

Perceptions change with time and new knowledge. The Great War wasn’t sparked by one thing (such as an assassination or European imperial rivalry), but rather by a concatenation of forces such as industrialism, nationalism, arms races, imperialism, new developments in weaponry, and the failures of the individuals involved in 19th century diplomacy.

Industrial and political revolutions

During the 19th and early 20th centuries the ongoing industrial revolutions saw railway and telegraph networks booming across Europe along with the internal combustion engine, petroleum, alloys and new chemicals.

At the same time it was a world of duty, pageantry, patriotism, nationalism, militarism and imperialism – slowly being undermined by the advances of Marxism and socialism.

It was a peculiar mix of modernity and démodé. It was a recipe for disaster.

According to Professor Gary Sheffield, the Great War represented a “clash of 20th century technology with 19th century military science”.

Bolt-action rifles, rapid-firing machine guns, smokeless powder, powerful rifled artillery with hydraulic recoil mechanisms and high explosive shells came into being. But they existed inside a British army which by 1917 still had more than a million horses and mules in service. Over the course of the war, says Sheffield, Britain lost 484,000 horses – one horse for every two men.

At the war’s outbreak, the massed ranks of cavalry marshalled on all sides symbolised the cruel evolution of warfare. They looked impressive; they were horribly vulnerable.

British proponents of cavalry had pointed to the brilliant performance of the mounted Boer sharpshooters in the recent South African war, maintaining that “the shock action of cavalry was still the essential tactical counterpart to infantry power”, according to Field-Marshall Viscount Montgomery in A History of Warfare, who opined, however, that by 1914 mounted troops had “outlived their usefulness in battle”.

The South African campaign gave the British a foretaste of what was to come. At the battle of Spion Kop in January 1900, a well dug-in Boer unit armed with (German-made) magazine-fed Mauser rifles inflicted grievous casualties on a British force almost devoid of cover.

Montgomery noted this had been called “the supreme day in the history of the rifle”. (p452)

Having learnt a painful lesson, the British produced their own model of deadly rifle fire with the new bolt action Lee–Enfield - its sustained “15 rounds rapid” or “mad minute” from each soldier made such an impression on the Germans at the Marne in 1914 that many thought they were being fired on by multiple machine-guns.

The difficulties accumulate

Most of the war’s generals were not stupid. They had some inkling of what lay ahead. Most of them had read Clausewitz:

“Everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult. The difficulties accumulate and end by producing a kind of friction that is inconceivable unless one has experienced war… ”

And there had been warnings that the next war would be far worse than any before.

Writing in 1898 the Russian economist Ivan S. Bloch declared that the invention of smokeless powder and quick-firing rifles had “effected as great a revolution in contemporary warfare as the introduction of printing with movable type accomplished in the caligraphic and illuminating arts of the Middle Ages”.

These innovations only excited curiosity “without arousing misgivings as to the ultimate consequences,” he said.

“Great is the conservatism of staff officers, and childlike the trust of rank and file in the thaumaturgic power of the past over the present and the future.”

‘The lamps are going out all over Europe’

The war began to go wrong in the first couple of months. The French, brooding over defeat and the loss of Alsace and Lorraine in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, believed it could defeat any German attack via its doctrine of constant offensive and the fierce elan of its troops.

Meanwhile, the Germans – following the Schlieffen Plan, which had been doctored by Moltke in an attempt to provide for every contingency – began the invasion of Belgium at 8.02am on August 4 with the same commitment to Bewegungskrieg (war of manoeuvre) which the Germans were to implement again in the early years of World War 2 (when it was named Blitzkrieg).

And then Britain quickly declared war on Germany. “Germans could not get over the perfidy of it,” wrote Barbara Tuchman. “It was unbelievable that the English, having degenerated to the stage where suffragettes heckled the Prime Minister and defied the police, were going to fight.”

But the British had guaranteed they would defend the neutrality of Belgium. When Germany refused to withdraw Britain – with its then small colonial army – went off to war.

In elegiac tones Britain’s Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey lamented: “The lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.”

The lamps were also going out on Moltke’s advance. His re-jigging of Schlieffen’s plan was fatally flawed and was exploited by the Allies at the Battle of the Marne and later at the Aisne and at Ypres. It was the closest the Germans got to winning the war.

For the French and the handful of British divisions then fighting with them this was, in the words of the military historian Basil Liddell Hart – writing just 10 or so years after the event – a “strategic but not a tactical” defeat of the German attack.

The Germans were able to regroup and dig in at Flanders in Belgium, and in so doing emphasised, in the words of Liddle Hart, “the preponderant power of defence over attack” with their “trench barrier … consolidated from the Swiss frontier to the sea”.

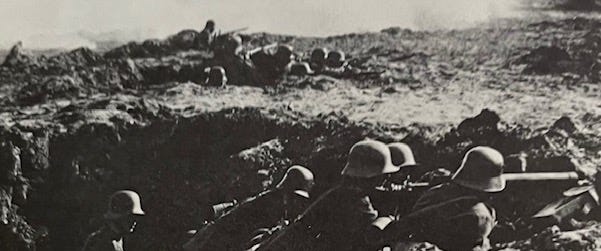

So was born the nightmare of trench warfare with its mud, machine guns, gas, barbed wire, and massed artillery – and the relentless, murderous slaughter of the “over the top” infantry advances.

Note that this was not the fault of the so-called “donkeys” - Haig and his generals and their allied equivalents. In the words of Professor John Bourne, there wasn’t a script to follow: “What they were doing was unique; no one had been asked to do it before or again”.

It was, says Bourne, like “learning to drive by having a series of road crashes”.

As Professor David Reynolds puts it, World War 1 did not follow a heroic narrative such as that attributed to World War 2.

‘A subject either for tragedy or for satire’

Many of the war poets depicted the conflict as a struggle of “immense futility run by men who were not up to the job and involving the sacrifice of soldiers on an appalling scale”.

The war, says Reynolds, appeared to be “a subject either for tragedy or for satire”.

There was tragedy aplenty as Allied commanders and troops struggled to overcome enemy positions, which for a large part were slightly uphill and atop the chalk substrata, which meant the enemy could construct bunkers and shelters that were immensely difficult to breach.

Everything commanders had learned about strategy, operations and tactics suddenly became redundant in an unprecedented horrorscape of blood and mud. Defence dominated the offensive, and the enemy – the German army – was a hard, unyielding, implacable, clever and courageous foe.

For much of the time in the first three years it was a grim war of attrition. Breakthroughs were planned but they often ended in mass casualties for little territorial gain.

The Flanders battlefields were replete with towns, villages, rivers, woods and landmarks whose names simultaneously ring both dolorous and dulcet: Passchendaele, Ypres, Messines, Arras, Thiepval, Beaumont Hamel, Loos, Neuve Chapelle, Messines, Verdun, Mametz, and the Somme.

It was at this last that the epic tragic battle was played out from July 1 to November 18 1916. It was not General Douglas Haig’s choice to fight at the Somme. General Joseph Joffre had demanded the British attack there in order to take the pressure off the French troops under siege at Verdun.

The intention, writes Liddel Hart, was to break the German front between Bapaume and Ginchy, push back the German flank to Arras, and then launch a general advance to Cambrai-Douia.

Colossal artillery barrage

The July 1 British infantry assault was preceded by a colossal artillery barrage lasting four days involving 445 guns ranging from trench mortars, 60-pounders, and massive 15-inch howitzers. In all, they fired around 1.5 million rounds.

If you were Haig you’d probably think “that’ll do it”.

Liddel Hart records that Haig “had suggested tentatively that, before the mass of infantry were launched, the result of the bombardment and the state of the defences might be tested by sending ahead patrols or small parties …But this suggestion was rejected by his army commanders”.

When the infantry burst forth from the trenches many were mown down before they could fire a shot, leading to 57,470 casualties including 19, 240 killed.

Each weighed down by 66 lbs of kit, the advancing troops were shredded by a storm of bullets and shells. Many of those who made it close to the German trenches found themselves helplessly trapped in barbed wire that had been barely damaged by the bombardment.

Historian John Keegan declared that “the battle was the greatest tragedy…of [Britain’s] national military history” and “marked the end of an age of vital optimism in British life that has never been recovered”.

Nevertheless, the seeds of a revolution in military affairs were sown in the later phases of the British Somme offensive, which began on September 15.

The tank – some 36 of them – made its debut. They were to have a much bigger impact in November 1917 when 381 of the beasts were unleashed to great effect at Cambrai.

The next year, in March 1918, following the collapse of Russia and Rumania, Ludendorff launched a massive offensive pushing through a 47 mile front astride the Somme valley from Arras to La Fere, forcing Gough’s army to retreat.

Then in May Ludendorff’s offensive bumped into something new – an American army led by General John Pershing. It was a sign of things to come.

Led by numerous tanks French, British and American soldiers attacked his north-east flank at the Marne salient. To add to the new-look war-making, allied aircraft joined the attack at the battle of Amiens.

The Germans were at last broken and hostilities ceased at 11am on November 11 1918. The War to End All Wars was over. One million British, Australian, New Zealand, Canadian and other allied troops were dead while a further 2,289,860 had been wounded.

Douglas Haig was on the winning side. He had been a senior commander from the very beginning when the small British army landed in France in 1914. I don’t think there is any doubt about his courage, his fortitude, his ability to bounce back after failure, and also his competence as a staff officer.

When Haig died in 1928 more than one million people lined the streets of London for the funeral procession – more than that for Princess Diana many years later. It is clear that many regarded him as a hero worthy of respect and remembrance.

World War 1 unlike any war before it

World War 1 was unlike any war before it in its scale, complexity, constantly developing technology, automatic weapons, aircraft, tanks, impact of weather conditions, and unprecedented large and well-equipped armies.

The top brass did not come out of it looking good.

For example, the authors of the Australian Official History were less than impressed by Haig’s generalship at the Somme.

“Even if the need for maintaining pressure be granted, the student will have difficulty in reconciling his intelligence to the actual tactics… To throw the several parts of an army corps, brigade after brigade … 20 times in succession against one of the strongest points in the enemy’s defence, may certainly be described as methodical but the claim that it was economic is entirely unjustified.” (in Liddell Hart, p326)

Montgomery, who served as a junior officer in World War 1 and was also seriously wounded, had some serious concerns about the quality of the senior staff.

“A remarkable, and disgraceful, fact is that a high proportion of the most senior officers were ignorant of the conditions in which the soldiers were fighting. The quality of the men who had to do the fighting contrasts with the quality of generals,” he wrote. (A History of Warfare, p 476)

Montgomery was a thoughtful and cautious general, no doubt a legacy of the Great War.

All the field marshals and generals in World War 1 were out of their depth because they were not prepared for the conflict that unfolded. They had to adapt or die (either literally or metaphorically).

What seems blindingly obvious to us was opaque to them because we live history back wards and they lived it forwards. We know what happens. They didn’t, until it did.

Why did they fight? I think the majority of officers and other ranks of all sides would echo the words of Faramir to Frodo in The Lord of the Rings (The Two Towers):

“I do not love the bright sword for its sharpness, nor the arrow for its swiftness, nor the warrior for his glory. I love only that which they defend …”

References

Ross Beadle, 'The Origins of the Schlieffen Plan', Western Front Association lecture -

J Bloch, The War of the Future in its Technical, Economic, and Political Relations, Paris, 1901.

Professor Vernon Bogdanor, 'Britain in the 20th Century: The Great War and its Consequences', lecture –

John Bourne, 'The BEF: The Final Verdict', Western Front Association lecture -

Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, Harper, 2013.

Sir Richard Evans, 'Politics and the First World War' lecture -

Robert Foley, 'Baptism of Fire: Germany's Lost Victory in 1914', Western Front Association lecture -

B H Liddell Hart, History Of The First World War, Book Club Associates, London, 1970.

John Keegan, The First World War, Hutchinson, London, 1998.

Alan Lloyd, The War In The Trenches, Book Club Associates, London, 1976.

Margaret MacMillan, 'The Changing Nature of European War 1815-1914', lecture -

Margaret MacMillan, 'The Road to 1914', lecture -

Field-Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, A History Of Warfare, Collins, London, 1968.

Sonke Neitzel & Harald Welzer, On Fighting, Killing and Dying. Soldaten. The secret WWII transcripts of German PoWs, Random House, 2012.

David Reynolds, 'How Our Perception Of WW1 Has Been Moulded Over Time - The Long Shadow', Timeline World History Documentaries -

David Reynolds, 'The Long Shadow: The Great War and International Memory 1914-2014' lecture -

Gary Sheffield, 'Douglas Haig: Hero of Scotland, Britain and the Empire', Western Front Association lecture -

Gary Sheffield, 'The Great War: Its End and Effects', lecture -

Wilfred Owen, Strange Meeting – Read by Tom O’Bedlam -

JRR Tolkien, The Lord Of The Rings, HarperCollins, London, 1991.

Barbara W Tuchman, The Guns of August, Penguin Books, London,