By DAVID MYTON

At Highgate Cemetery, London, on March 17 1883, Friedrich Engels stood by the grave of his long-time friend and colleague, Karl Marx, and delivered a short but heartfelt eulogy.

Marx’s death, he said, was an immeasurable loss to the proletariat of Europe and America. He would be remembered by many.

“Just as Darwin discovered the law of development of organic nature,” said Engels, “so Marx discovered the law of development of human history: the simple fact, hitherto concealed by an overgrowth of ideology, that mankind must first of all eat, drink, have shelter and clothing, before it can pursue politics, science, art, religion.”

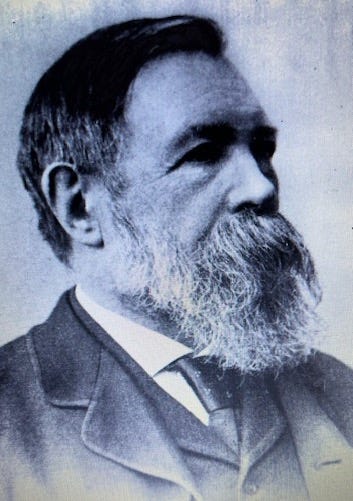

That was not all. Marx also discovered “the special law of motion governing the present-day capitalist mode of production, and the bourgeois society that this mode of production has created”, said Engels (pictured above).

“The discovery of surplus value suddenly threw light on the problem, in trying to solve which all previous investigations, of both bourgeois economists and socialist critics, had been groping in the dark.”

Two such discoveries would be enough for one lifetime. “But in every single field which Marx investigated - even in that of mathematics - he made independent discoveries”

Above all though, Marx was a revolutionist: “His real mission in life was to contribute, in one way or another, to the overthrow of capitalist society and of the state institutions which it had brought into being [and] to contribute to the liberation of the modern proletariat…”

Marx, said Engels, had died beloved … revered and mourned by millions of revolutionary fellow workers from the mines of Siberia to California to all parts of Europe and America. And though “he may have had many opponents, he had hardly one personal enemy”.

However, what Engels didn’t say is that Karl Marx would never have become that famous political theorist, economist, journalist, philosopher, socialist etc., without the extraordinary contribution of a certain … Friedrich Engels, who, according to biographer Terrell Carver, was “a partner in the most famous intellectual collaboration of all time”.

In his 1845 Theses on Feuerbach Marx wrote that “philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it”.

Engels was in full agreement with this, and to a large extent that change, in the view of Engels, was not necessarily primarily political, but rather social - especially living conditions. In Marx’s base and superstructure model, housing and good working conditions were firmly at the base.

Engels collaborated with Marx on numerous publications, but he also wrote much himself including articles, pamphlets, reviews and books.

“In many of these he attempted to explicate Marx’s premises and views, to which he had substantially contributed. He also became Marx’s reviewer and editor, writing prefaces for new editions of his (and their) works and preparing Marx’s manuscripts for publication after the senior partner’s death in 1883,” writes Terrell Carver. (See References below)

Basic to Marx and Engels’ thought is the notion that society comprises a foundational economic base and an overarching superstructure. The base comprises the economy, the means of production, capital, labour, and worker-owner relations. Ideas of politics, ideology, law, and religion sit in the superstructure.

Prosperous family

Engels came from a prosperous middle-class German family. His father was an industrialist in the textile business, and owner of factories in Barmen, Bremen, and also in Manchester, England.

Although he disapproved of his son’s politics and the company he kept, he gave him a position at the Manchester factory. Engels hated the work, but he was good at it, as he was at most things. He went fox hunting with the gentry he despised, and eventually became a partner in the business - and the income helped him keep Marx out of poverty.

What motivated Engels in his political life? What was the base on which his intellectual and philosophical superstructure rested?

It was the Industrial Revolution, as experienced in England. In the words of historian EP Thompson, the working class had been “subjected simultaneously to economic exploitation and political oppression leading to mass immiseration and suffering. The process of industrialisation was carried through with exceptional violence in Britain … this violence was done to human nature”.

The work at the factory inspired Engels, then aged 22, to find out what life was like for those at the bottom of the rung. From his investigations he wrote a book - The Conditions of the Working Class in England, first published in 1844. The English language edition came out in 1887.

What did he find? The following is extracted from his book:

Death by starvation

“Every working-man in England is constantly exposed to loss of work and food, that is to death by starvation, and many perish in this way,” he writes.

Not only that - “The dwellings of the workers are everywhere badly planned, badly built, and kept in the worst condition, badly ventilated, damp, and unwholesome.”

The inhabitants are confined to the smallest possible space, and at least one family usually sleeps in each room. Working and living conditions were horrendous, Engels wrote.

“During my residence in England, at least twenty or thirty persons have died of simple starvation under the most revolting circumstances, and a jury has rarely been found possessed of the courage to speak the plain truth in the matter.

“Let the testimony of the witnesses be never so clear and unequivocal, the bourgeoisie, from which the jury is selected, always finds some backdoor through which to escape the frightful verdict, death from starvation. The bourgeoisie dare not speak the truth in these cases, for it would speak its own condemnation.”

The English working-classes, says Engles, call this “social murder”, and “accuse our whole society of perpetrating this crime perpetually”.

Who was to blame for all of this? It was the Bourgeoisie, he declared.

“I have never seen a class … so incurably debased by selfishness, so corroded within, so incapable of progress, as the English bourgeoisie … It knows no bliss save that of rapid gain, no pain save that of losing gold.”

Everywhere there was “barbarous indifference, hard egotism on one hand, and nameless misery on the other, everywhere social warfare, every man’s house in a state of siege …

“Since capital, the direct or indirect control of the means of subsistence and production, is the weapon with which this social warfare is carried on, it is clear that all the disadvantages of such a state must fall upon the poor. Cast into the whirlpool, he must struggle through as well as he can … what security has the working-man that it may not be his turn tomorrow? Who assures him employment?

“Who guarantees that willingness to work shall suffice to obtain work, that uprightness, industry, thrift, and the rest of the virtues recommended by the bourgeoisie, are really his road to happiness? No one.”

The worker knows that, though he may have the means of living today, it is uncertain whether he shall tomorrow … “Every working-man, even the best, is therefore constantly exposed to loss of work and food, that is to death by starvation, and many perish in this way.

“The dwellings of the workers are everywhere badly planned, badly built, and kept in the worst condition, badly ventilated, damp, and unwholesome. The inhabitants are confined to the smallest possible space, and at least one family usually sleeps in each room.

Poverty-stricken

“The interior arrangement of the dwellings is poverty-stricken in various degrees, down to the utter absence of even the most necessary furniture … The food is, in general, bad; often almost unfit for use, and in many cases, at least at times, insufficient in quantity, so that, in extreme cases, death by starvation results.

“Thus the working-class of the great cities offers a graduated scale of conditions in life, in the best cases a temporarily endurable existence for hard work and good wages - in the worst cases, bitter want, reaching even homelessness and death by starvation … the worker is, in law and in fact, the slave of the property-holding class, so effectually a slave that he is sold like a piece of goods.

“If the demand for workers increases, the price of workers rises; if it falls, their price falls. If it falls so greatly that a number of them become unsaleable, if they are left in stock, they are simply left idle; and as they cannot live upon that, they die of starvation.

“… The only difference as compared with the old, outspoken slavery is this, that the worker of today seems to be free because he is not sold once for all, but piecemeal by the day, the week, the year, and because no one owner sells him to another, but he is forced to sell himself in this way instead, being the slave of no particular person, but of the whole property-holding class … it is not surprising that the working-class has gradually become a race wholly apart from the English bourgeoisie.”

REFERENCES

Terrell Carver, Engels, Oxford University Press, 1981.

Frederick Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England - https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/condition-working-class/index.htm

Harry Hearder, Europe In The Nineteenth Century 1830-1880, Longman, London, 1988.

James Joll, Europe Since 1870. An International History, Penguin, 1982.

John McManners, Lectures On European History 1789-1914. Men, Machines and Freedom, Blackwell, Oxford, 1966.

Agatha Ram , Europe In The Nineteenth Century 1789-1905, Longman, London, 1984.

E P Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, Gollancz, London, 1963.

Thank you so much loved learning more about Engels. I've always been fascinated about their dynamic and relationship. Makes me wonder how they met

This is an eloquent eulogy but would love something more comprehensive from you :) - for example the question did Engels take the ball from Marx and run a little bit in a slightly different direction? Remember, Karl was supposed to have said “I am not a Marxist”. Now I don’t think he had Freddy in mind, but I think it’s an intriguing theme.