By DAVID MYTON

The New York-based author and academic Professor Stuart Ewan says that the history of Public Relations “is a history of a battle for what is reality and how people will see and understand reality” while scholar and author Nikos Kazantzakis recommends that “since we cannot change reality, let us change the eyes which see reality”.

So who are you going to call when you need not only to market your own success but also to impugn the reputation of potential competitors? And who does it all with unrivaled genius and long-lasting results?

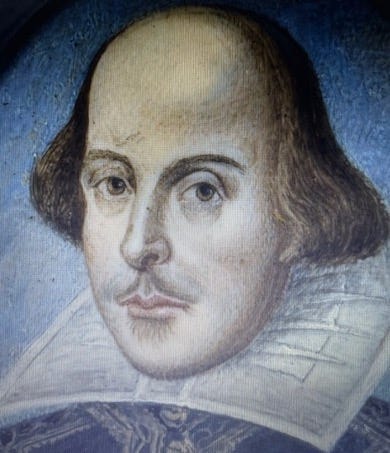

Well, it’s got to be William Shakespeare, playwright, poet, actor and “the best writer we ever will know” whose “principal characters have become our mythology”, according to scholar and critic Harold Bloom in Shakespeare. The Invention of the Human. (Full details of books cited below)

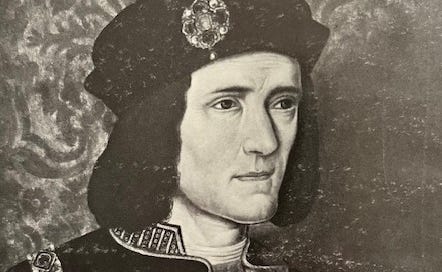

One of Shakespeare’s most well-known characters is King Richard III, who was killed and his army defeated at the Battle of Bosworth in the final battle of the Wars of the Roses, a civil war between the House of York and the House of Lancaster, which had kicked off in 1455.

His death brought to an end the English royal House of Plantagenet, whose kings had reigned in England since 1154. The victor, Henry Tudor, inaugurated the Tudor dynastic reign when he was crowned as King Henry VII on October 30, 1485.

Not everyone in the realm was happy with that, especially erstwhile Yorkists. Who was this Henry guy? Apart from winning a battle, what gives him the right to be our King?

Nevertheless the Tudors dug in and were enthroned for many years. The notorious much-married Henry VIII reigned from April 22 1509 until his death in 1547 with his daughter Elizabeth (via the executed Anne Boleyn) eventually being crowned Queen on November 17 1558, reigning for 45 years until she died in 1603 - the last of the Tudors.

Elizabeth proved to be an exceptionally effective and accomplished monarch. When she ascended to the throne England was not in good shape - it was a victim of itself and of its competitors, “almost too far behind them to be called an also-ran”.

When Elizabeth died having reigned for 45 years, “England was the richest and most powerful nation in Europe and well on its way to becoming the greatest empire the world has ever known”, writes Alan Axelrod.

Elizabeth understood the value of image-building combined with action. Says Axelrod: “Elizabeth began life as a bastard outcast, barely able to hold on to life. Made queen, she worked quickly to transform the image of her identity from a daughter of sin to the Virgin Queen. In the process, she created one of history’s most effective images of leadership.”

Elizabeth knew that image counts, and not just superficially. A leader is a human, a thinker, and a decision maker “but he or she is also a profound symbol, the embodiment of the entire enterprise … Elizabeth devoted much effort to styling and perfecting her image”.

Elizabeth didn’t literally instruct Shakespeare to write a play about King Richard, portraying him as a diabolical villain. She didn’t have to - Shakespeare knew what she wanted. He had no doubt read Sir Thomas More’s description of Richard as “little of stature, ill-featured of limbs, crooked back, envious, perverse, deep dissembler, arrogant, pitiless and cruel” among many other such choice descriptions. (Sir Thomas More, The History of King Richard III, 1513)

Shakespeare was shaped by the age in which he lived. As such, he would have been very aware of the fate awaiting traitors - beheaded, the victims’ severed heads being put on public display over the London drawbridge gate.

As Helen Cooper writes: “In 1606, the year in which Macbeth was probably written, the heads of Guy Fawkes and his fellow conspirators [they plotted to blow up Parliament] were put on public display … the last head was displayed in 1678.”

And so Shakespeare’s achievement with his play Richard III “is his permanent imposition of the official Tudor version of history upon our imaginations”, writes Harold Bloom.

Shakespeare, he says, gives the audience a hero-villain version of Richard who is “a compound of charm and terror”, a murderer, torturer, terrifying: “To invent Richard is to have created a great monster.”

King Richard ruled England for a mere 26 months - one of the shortest reigns in English history.

“Yet few English monarchs have exercised so compulsive a posthumous fascination for the English-speaking peoples,” writes Charles Ross.

“For all this, that greatest of English publicists, William Shakespeare, is largely responsible. Shakespeare made Richard into an archetypal villain.”

Historian Alison Hanham says Shakespeare’s Richard III is a “serious departure from the truth” - a Tudor picture of history “which nobody now would mistake for authentic history … it is Shakespeare who turns crooked shoulders into a hunched back”.

Paul Murray Kendall writes that Shakespeare’s Richard III “endorses the political attitude of the day which enjoyed contrasting the blessings of Tudor despotism with the preceding horrors of civil discord”.

Shakespeare’s Richard is “realised not as an arch-villain, but the personification of arch-villainy … before the average person has come to any serious study of English history, he has once for all identified Richard III as a monster hunched of back, withered of arm, and twisted of countenance …

“Shakespeare’s Richard III, the Tudor myth, has by and large, maintained its sway over scholars as well as the public.”

During Elizabeth’s reign the very strong message from the Crown was that Richard was a usurping monster who never legitimately ruled England.

Shakespeare was anything but stupid so he stuck with the program, presenting audiences with a monstrous, demonic Yorkist King … and stayed alive to write many more great plays.

REFERENCES

Alan Axelrod, Elizabeth I CEO. Strategic Lessons From The Leader Who Built An Empire, Prentice Hall Press, 2000.

Harold Bloom, Shakespeare. The Invention of the Human, Fourth Estate, London, 1999.

Helen Cooper, Shakespeare and the Medieval World, Bloomsbury, 2010.

Alison Hanham, Richard III And His Early Historians 1483-1535, Clarendon Press, London, 1975.

Paul Murray Kendall, Richard the Third, Book Club Associates, London, 1973.

Sir Thomas More, The History of King Richard III, 1513.

Jeremy Potter, Good King Richard? An Account of Richard III and his Reputation 1483-1983, Constable, London, 1983.

Charles Ross, Richard III, Eyre Methuen, London, 1981.

In fairness to Shakespeare, the way Richard became King and the mystery surrounding the fate of his nephews had already paved the way of his image as a villain.

"Out of my sight! Thou dost infect mine eyes."