And God made the two great lights, the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night; he made the stars also. And God set them in the firmament of the heavens to give light upon the earth, to rule over the day and night, and to separate the light from the darkness. And God saw that it was good. - The Holy Bible (RSV) Genesis v16-18

By DAVID MYTON

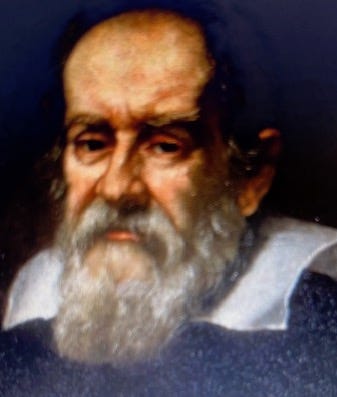

In 1609 Galileo Galilei, a scientist of great repute, built a telescope (perhaps the very first) from scratch. Being the genius he was, he sourced the lenses (one plano-convex objective and one plano-concave divergent), ensured they were correctly aligned, secured the tube to a one meter stand, and pointed it at the evening sky at precisely the correct angle.

On that starry starry night his eye took in the Milky Way, Jupiter and four of its orbiting moons, the cratered surface of the Moon, its valleys and mountains, and, most significantly, Venus, which he observed passing through phases from a thin crescent to a full disc and back again.

This, he deduced, could only mean that Venus orbited the Sun and not the Earth. As did all the planets in our solar system.

Galileo’s findings would change the way humans think about God, the universe, and planet Earth. They would also put his life and liberty in danger.

Galileo had built on the work of the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who in his 1530 treatise De Revolutionibus made the shocking claim that the Sun was the centre of the universe and that the Earth revolved around it.

This was contrary to the accepted teaching derived from Aristotle and Ptolemy, authorised by the Roman Catholic Church, that the Sun and all the stars revolved around a stationary Earth.

However, Copernicus - who died in 1543 - had a guardian angel in the form of his editorial supervisor, the Lutheran Minister Andreas Osiander, who in the preface of the book wrote that the work was merely theoretical and not to be taken literally.

The celebrity scientist

In the meantime Galileo - whose day job was mathematician-philosopher at the Court of Grand Duke Ferdinando II of Tuscany - continued to live as something of a celebrity scientist. His fame was slowly spreading throughout Italy.

He decided to write up his findings in a book titled Sidereus nuncius (The Starry Messenger), which included 70 drawings and technical impressions of Jupiter’s Medicean Stars, various constellations including Taurus and the Pleiades, the Moon, plus his ideas and theories about what it all meant.

Modestly, he thanked God “for being so kind as to make me alone the first observer of marvels kept hidden in obscurity for all previous centuries”.

He dedicated the book to Grand Duke Cosmino II de’Medici, naming the newly discovered satellites of Jupiter, the Medicean Stars - “thus inscribing the Medici name in the heavens for all time”. (Amir Alexander, Infinitesimal. How a Dangerous Mathematical Theory Shaped the Modern World, p81)

Now head mathematician of the University of Pisa, Galileo energetically engaged in debates and disputes, conceding that if there was no scientific proof of a particular thesis one should “accept the authority of Scripture understood in its most simple and direct meaning”.

However, he insisted the planets “did indeed revolve around the Sun and the Church would only discredit itself by contradicting manifest truth”. (Alexander, p85)

He maintained that several important biblical passages “were perfectly consistent with Copernicanism” and argued that heliocentrism was not contrary to the Bible’s teachings. And in any case the Bible was an authority on faith and morals, not science.

Galileo ‘may have committed heresy’

Meanwhile, as Galileo’s findings garnered more publicity his views encountered growing criticism. In 1613 a professor of philosophy at the University of Pisa, Cosimo Boscaglia, claimed Galileo may have committed heresy by publicly defending Copernicus’s heliocentric theory.

And in 1614 a Dominican friar, Tommaso Caccini, in a snarling sermon in Florence, denounced both Copernicus and Galileo for their blatant non-Scriptural assertions that the Earth was the centre of the Universe. Nevertheless, Galileo continued to engage in debates and discussions regarding the implications of his heliocentric claims.

Then in 1616 the Church - represented by the Italian Jesuit Cardinal Robert Bellarmine (a distinguished professor of theology) - decided to investigate Galileo personally.

Acting on the orders of the Pope, the Cardinal summoned Galileo to Rome for a grilling and to warn him that a new decree by the Congregation of the Index had officially condemned Copernicus’s assertion that the Sun, not the Earth, was the centre of the universe contrary to the teaching of Scripture.

As Amir Alexander writes “… seventeenth-century religious authorities were not inclined to look kindly on an uninvited intrusion onto their turf. Granted, Galileo was a gifted astronomer but he had no business pronouncing on theology, a field in which he was strictly an amateur.” (Infinitesimal, p16)

‘The Bible not a scientific book’

Bellarmine contended that no actual proof existed for Copernicus’ and Galileo’s claims. Since no such proof had been shown to him “One must stick to the manifest meaning of Scripture and the common agreement of the holy fathers … who all agreed that the Sun revolves around the earth.” (Op cit p84)

Galileo opined that the Bible was not a scientific book, and where it conflicted with common sense it was being allegorical. (Stephen W. Hawking, A Brief History Of Time. From the Big Bang to Black Holes, pp 189-190)

But Bellarmine was not to be persuaded. Galileo could not show him any proof. Therefore, Bellarmine warned him that in future he was not to defend Copernican theory and not to insist it was true, but to regard it as a hypothesis.

In 1616, the Church’s Holy Office officially decreed that Copernican theory was “false and erroneous”. Nevertheless, the Church would continue to hold Galileo in high esteem - indeed, he was granted an audience with Pope Paul V, who appeared friendly and assured him of his goodwill.

And so time passed and Galileo continued to do his genius thing, solving mathematical and geometrical problems but also regularly trying to unravel the riddles of the universe - which he thought he had done, to some extent, proposing a theory of tides in 1615 and a few years later a theory concerning comets. Both of these suggested the Earth was indeed moving.

Then in 1632, in a popular book titled Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, Galileo - oblivious of all danger - once more inter alia defended heliocentrism. With that, the Church had had enough.

In September 1632 the Inquisition summoned Galileo to Rome to face interrogation on a charge of heresy. He was 70 years old.

Fronting the Inquisition

Galileo was accused, among other things, “of holding as true a false doctrine that the sun is immovable in the centre of the world, and that the earth moves with a diurnal motion”; and for “instructing students in the same opinions, and for answering objections produced from the Holy Scriptures by altering the scriptures according to his own meaning”. See full charge sheet here.

Between 1632-33 he was questioned three times by the Inquisition, and at least on one of those occasions he was threatened with torture. He was ordered to “abjure, curse, and detest” his heliocentric opinions.

He was found to be “vehemently suspect of heresy” and was to be imprisoned “at the pleasure of the Inquisition”, which could mean for the rest of his life. The judgment declared, in part:

“The proposition that the sun is in the centre of the world and immovable from its place is absurd, philosophically false, and formally heretical; because it is expressly contrary to Holy Scriptures. The proposition that the earth is not the centre of the world, nor immovable, but that it moves, and also with a diurnal action, is also absurd, philosophically false, and, theologically considered, at least erroneous in faith.”

Then at last Galileo publicly recanted his opinions, which saved him from jail and possibly death. His sentence was commuted to permanent house arrest. He spent the rest of his life confined to his home (thankfully a pleasant villa) in Arcetri, near Florence. The book he wrote in 1632, Dialogues on the Two Chief Systems of the World, was banned.

In November 1992 - more than 300 years after the event - Pope John Paul II officially declared Galileo had been right. The committee set up by the Pope to investigate Galileo declared the Inquisition had acted in good faith, but was wrong.

REFERENCES

Amir Alexander, Infinitesimal. How a Dangerous Mathematical Theory Shaped the Modern World, Oneworld Books, London, 2014.

Paul Davis, The Mind Of God. The Scientific Basis for a Rational World, Simon & Schuster, 2005.

Stephen W. Hawking, A Brief History Of Time. From the Big Bang to Black Holes, Bantam Books, London 1988.

R. N. Swanson, Religion and Devotion in Europe, c.12.15-c1515, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

This article was inspired by my extraordinarily talented wife, Rimma.

Thanks Alice, I’m planning to write a piece next week looking at the Church’s perspective. Regards, David M

Establishing one of the basic propositions of logic : majorities are irrelevant in determining facts.