Hacked to death in battle: the grim fate of King Richard III and how it came about

Why the last Yorkist monarch had no choice but to fight for his right to reign

By DAVID MYTON

King Richard III of England was killed and his army defeated in the final battle of the Wars of the Roses, a civil war between the House of York and the House of Lancaster, which had kicked off in 1455.

His death brought to an end the English royal House of Plantagenet, whose kings had reigned in England since 1154. The victor Henry Tudor inaugurated the Tudor dynastic reign when he was crowned as King Henry VII on October 30 1485.

This whole period of the Wars of the Roses is one of the most complex, bloody and fascinating in English history.

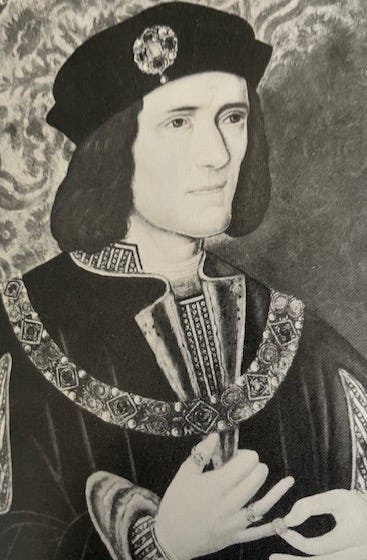

Now there is a significant barrier to be overcome in trying to understand King Richard's motives. And that's the diabolic portrayal of Richard in William Shakespeare's play Richard III which, in the words of the literary critic Harold Bloom, presented Richard as “a sado-masochistic compound of charm and terror” which left the “permanent imposition of the official Tudor version of history upon our imaginations”.

Shakespeare's hunchbacked Richard is portrayed as a “deformed, unfinished person” determined to be a “subtle, false and treacherous” villain.

But the psychologists Mark Lansdale and Julian Boon in a penetrating analysis of Richard say there is no strong evidence that he exhibited much by way of an abnormal or psychopathic personality disorder. If anything, they say, the evidence suggests the opposite.

As for being a “hunchback”, when researchers from the University of Leicester discovered Richard's skeletal remains in 2012-13, they found he actually suffered from right-sided scoliosis, and any disfigurement he had would have been quite slight.

His torso would have been short relative to the length of his limbs, and his right shoulder a little higher than his left, but it was “nothing that a good tailor couldn’t disguise”. (See References below for link to this fascinating research).

Richard also stands accused of murdering the so-called “little princes in the Tower” - the two young sons of his late brother King Edward IV. But there's no hard proof of that.

As the historian Paul Murray Kendall writes, if we take evidence to mean testimony that would secure a verdict in a court of law, then there is no evidence that he murdered the princes.

Bosworth? Richard had never heard of it

Now as Richard proceeded with his army to fight Henry, the name Bosworth would not have been in his mind. At that time, the location of the battle did not bear that name.

As historian Peter Hammond says, earliest records named the site as Redemore or Redesmore, among others.

The first record naming Bosworth for the battle appeared in the Great Chronicle of London, written about 1512. This is important because there was never a point when Richard thought “right, I'll fight Henry at Bosworth, it's a top spot for a battle”.

When he set off with his army he knew approximately where a clash might take place, but not precisely.

I do not believe that Richard did make a decision to fight Henry at Bosworth.

The Cambridge English Dictionary defines the word decision as “a choice that you make about something after thinking about several possibilities”.

In my view Richard did not make a rational, calculated, cost-benefit decision in consultation with others, about Bosworth. The truth is he had no choice. He had to fight Henry, he had to crush his army, he had to stamp out numerous pro-Tudor rebellions - and he had to do it now, before Henry got much farther.

Richard was a warrior who had proven his worth in battle. For him and his contemporaries, wars were simply politics by other means.

Richard had fought with courage and great effectiveness alongside his handsome and rakish brother Edward IV in the Wars of the Roses - particularly standing out at the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury.

At that stage Richard was titled the Duke of Gloucester, and he was greatly admired as “the Lord of the North” a “bestower of aid as well as judgment to all manner of men and causes”.

An epoch suffused with religion from cradle to grave

Certainly, Richard was no angel. But he wasn't a devil either. He existed in the Medieval era, an epoch “suffused with religion from cradle to the grave and beyond”.

As historians Julian Pollock and Katrin Kania write, the major force in the universe was God, and angels and devils were responsible for moving the planets.

It was, says historian Paul Murray Kendall, “a changing, trans-shifting, restless time of witches, superstition, and fear of the unknown”.

Trailblazers such as Copernicus, Michelangelo, Raphael, Erasmus, Martin Luther and Christopher Columbus were still all very young and hadn't yet made their big time discoveries and works that left their mark on the world. It was all before that.

Richard was locked within a medieval zeitgeist in which Earthly life was only a part of existence. It was a preliminary to the afterlife of Heaven or Hell.

And Richard believed in the power of prayer. His personal prayer book - his Book of Hours - contains this plea to Jesus Christ:

Deign to free me

Thy servant King Richard

From all the tribulations grief and anguish in which I am held

And from the snares of my enemies

Free me from all the tribulations

Griefs and anguishes which I face

In a prayer in his Book of Hours, Richard begs God to be “delivered from the plots of my enemies and to find grace and favour in the eyes of my adversaries and all Christians”.

So Richard had put himself in the hands of God to aid him in his cause against Henry – in a sense, he “outsourced” his decision-making to the Almighty.

And why wouldn't he? His reign was no easy ride. There were all kinds of troubles within the kingdom, and he had to deal with some personal tragedies also.

In early April 1484 Richard's young son and heir, Edward the Prince of Wales, unexpectedly died after a short illness.

Richard and Anne, his wife, were left childless, bereft and devastated. Historian Chris Skidmore records that such was their grief that “father and mother were left in a state almost bordering on madness”.

Then on March 16 1485 Richard's wife and queen, Anne, died possibly of tuberculosis.

A rumour spread that Richard had poisoned her so that he could marry his niece Elizabeth of York, who in fact went on to wed the newly installed Henry VII on January 18, 1486.

Richard had to expend much energy crushing these and other rumours on top of which, in an emotionally exhausted state, he had to tend to the management and defence of his kingdom.

Richard must fight – there was no other choice

He knew Henry would come soon, and as anointed King by the will of God Richard must fight for his realm. There was no other choice.

He was exhausted and conflicted but he still had to confront Henry – he couldn't take time off to recuperate.

And so given who he was, and when and where he was, there was really nothing for Richard to decide. He must stamp out the threat posed by his Tudor enemy; he had to do it now, and he prayed to God for help.

On August 8 1485 Henry, along with around 2000 French mercenaries, landed at Milford Haven on the Welsh coast.

He marched to Shrewsbury then to Newport, Stafford, Tamworth and Atherston and as he went along he gathered more rebel troops to his cause.

When Henry landed Richard had been waiting at Nottingham, which is where he heard of Henry's arrival. So wearing the King's golden crown on his helmet, mounted on a white palfrey, and with trumpets blowing in a deliberate morale-raising measure, Richard rode out to do battle wherever it would be.

Richard was betrayed by his former ally Sir William Stanley, who at the last minute joined forces with Henry Tudor on top of the complete inaction of another traitor, the Earl of Northumberland. All this sealed Richard's fate.

Harried on all sides, the last of the Yorkist kings placed his crown upon his helmet and charged into the fray, crying that he would die as King or win.

He perished, hacked to pieces in the melee. His body, stripped of armour and clothes, was thrown naked over the back of a horse and taken to Leicester where it was placed on public display for two days before being unceremoniously buried.

At the age of 32 Richard was the last English king to die in battle – one that he had no choice but to fight.

When the news of his death reached York, the city fell into mourning for a man they called “the most famous prince of blessed memory”.

References

The Richard The Third Society - http://www.richardiii.net/

Harold Bloom, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, Fourth Estate Limited, London, 1998

A H Burne, The Battlefields of England, Penguin Books, London, 1950

Peter Hammond, Richard III And The Bosworth Campaign, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, 2010

Winston S Churchill, A History Of The English Speaking Peoples, Cassell, London 1998

Mark Lansdale and Julian Boon, The Man Himself. Richard III – a psychological portrait, The Richard III Society -http://www.richardiii.net/2_6_riii_psychological.php

Paul Murray Kendall, Richard The Third, Book Club Associates, London, 1973

Lloyd and Jennifer Laing, Medieval Britain. The Age of Chivalry, Herbert Press, London, 1998

University of Leicester, Richard III: Discovery and Identification - https://le.ac.uk/richard-iii/identification/osteology/scoliosis

Gillian Polack and Katrin Kania, The Middle Ages Unlocked. A Guide To Life In Medieval England, Amberley Publishing, Gloucestershire, 2015

Chris Skidmore, Richard III. Brother Protector King, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 2017

R N Swanson, Religion and Devotion in Europe c1215-c1515, Cambridge Medieval Textbooks, Cambridge University Press, 1995