JF Archibald's boisterous Sydney Bulletin: a carnival of mockery, ridicule and comedy

The secret of its success ... 'half Australia writes it, all Australia reads it'

This is the fifth extract of chapters of my work on John Feltham (aka Jules Francoise) Archibald 1856-1919, founding editor of the Sydney Bulletin – one of the most popular newspapers in Australia’s history.

By DAVID MYTON

There has never been a newspaper like the Sydney Bulletin in the period 1880-1903. It was a rambunctious carnival of comedy, cheek and mockery; but also serious, analytical and thoughtful. These facets were all held in a creative balance thanks to the genius of its editor, J F Archibald.

The paper took Australia and Australians seriously. It never talked down to them. It is famed for its short, snappy paragraphs and hilarious, satirical cartoons. However, there were also long, studious articles ranging across myriad topics, from religion to politics, war to race.

It asked the public to contribute paragraphs, poems and stories – which they did in their thousands on subjects from surviving in the bush to the perils of the city. The paper’s esteemed literary editor, A G Stephens, estimated it received some 200 contributions every day.[i]

As a saying of the times had it: “Half Australia writes it, all Australia reads it”.[ii]

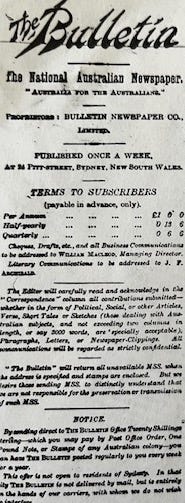

If it didn’t talk down to them, the Bulletin didn’t mind giving its readers and contributors the occasional lecture. “In writing to The Bulletin,” said one instruction, “remember it is only a little paper and not one to maunder in. We wouldn’t allow three and half columns to William Shakespeare.”[iii]

By opening its pages to the people of Australia, Archibald ensured his paper’s popularity. Circulation reached 80,000 in the late 1880s (readership would perhaps be four times this number), a considerable achievement at a time when the New South Wales population had just touched one million.

Archibald encouraged them all, a regular notice in the Bulletin declaring:

“Every man can write at least one book; every man with brains has at least one good story to tell; every man, with or without brains, moves in a different circle and knows things unknown to any other man … mail your work to the Bulletin, which pays for accepted matter.”

Sub-editors are the unsung heroes of newspapers. Theirs is not the glamorous job of police rounds or political reporting. Instead they edit and fact check copy.

The editor may require them to turn 30 paragraphs into 10, retaining the same amount of information, while maintaining the flow. The intro may be too long, so they’ll cut it back and, more often than not, improve it. Thanks to a broad education and sharp minds, they have rescued many a paper from a defamation action or will have saved face by correcting the spelling of some famous person’s name. They also write the headlines and captions for photographs and illustrations.

Archibald was a brilliant sub-editor but he described himself modestly as a “soler and heeler of paragraphs”. With his famous blue pencil he would work alchemy on rambling poems or limping stories, turning them into golden paragraphs that said all they needed to say.

A journalist who knew him, Claude McKay, called Archibald’s work “sublime”, adding “when he found a gleam of intelligence he would set it in a shining paragraph”.[iv]

As the Australian author Vance Palmer put it:

“Sitting in his shirtsleeves at his cluttered desk he would sort out the masses of tangled script that came pouring into his office, his eyes gleaming behind their pince-nez if he came upon something that could be given life.”[v]

Archibald was a talent spotter extraordinaire. Australian literature will be forever in his debt for “discovering” or at least providing a platform for some of the nation’s renowned authors and poets: Banjo Paterson, Henry Lawson, Tom Collins (Joseph Furphy), Bernard O’Dowd, Edward Dyson, Victor Daley, Barbara Baynton, Henry Kendall, Barcroft Boake, Louis Becke, Will Ogilvie, Ethel Turner, to name only some. These and more were published in the Bulletin and many benefited from Archibald’s incisive, creative editing.

Claude McKay says Archibald exalted the anecdote and the ballad:

“I began to realise what the early Bulletin writers must have owed to him. At times I would compare an original set of verses with the form in which Archie sent them to the printer. Not one line remained unaltered. But the verse sang. Archibald liked a musical lilt.”[vi]

Academics and literary critics may squirm at the description of many of these writers as “great”. But they were: in their time and place, in conditions of enormous challenge, they laid the bedrock of an Australian literary tradition.

In the Bulletin, said Leon Cantrell “there developed a literature which spoke of and for the Australian people …”[vii]

Taken together, the significance of these works is that they show writers “grappling robustly with the life around them, discarding false values, and addressing their own countrymen in an unaffected way instead of raising their voices to attract an overseas audience”.[viii]

They helped to make sense of life in a new (for Europeans) land - a hard, harsh country but also one of abundance. Australia, they affirmed, was more than a colonial offshoot of Great Britain; it was its own self, unique, significant and important. It had its own stories to tell.

The Bulletin’s contribution to Australian literature was made even more significant with the appointment by Archibald in 1894 of the Queensland journalist Alfred George Stephens[ix], forever known by his initials A G.

Stephens established the Red Page, a weekly forum for literature of all kinds. Like Archibald he was a superb editor, but unlike Archibald he was not shy in making his views known. Although he was a sharp critic, he nevertheless opened up the Red Page to numerous authors and poets along side his various critiques and selections of European and American works.

He gave encouragement, support and a platform for the likes of Barcoft Boake, Steele Rudd, Chris Brennan, Bernard O’Dowd, Hugh McCrae and Miles Franklin, among others. Victor Daley gave this humorous account of AGS at work:

“The Red Page Editor discovered sitting … in his shirt sleeves. Proof sheets of new Australian poems on his desk. Coils of more new Australian poems (in manuscript) hanging over the back of his chair. He reads one of the latter, and mutters, shaking his head: ‘Won’t do. Lacks the indefinable something which is the soul of Poetry. Must define that one of these days!’ … Hums softly –

I am the Blender of the pure

Australian Brand of Literature.

No verse, however fine, can be

The radiant thing called Poetry

Unless it is approved by me.[x]

Archibald’s contribution to all this was deft management. He gave Stephens his head, and Stephens repaid him by turning the Red Page into the most talked about, discussed and read section in contemporary Australian newspapers.

In the next chapter we will see how Archibald and the Bulletin created a literary legend.

[i] Leon Cantrell (ed), ‘The Bulletin Den’, in A.G. Stephens: Selected Writings, Angus & Robertson, 1978, p33

[ii] Sylvia Lawson, The Archibald Paradox. A Strange Case of Authorship, Allen Lane, Sydney, 1983, p165

[iii] Bulletin, March 2 1895, p6

[iv] Claude McKay, ‘J.F. Archibald Was A Living Legend’, The Sunday Herald, November 23, 1952, p12

[v] Vance Palmer, The Legend of the Nineties, Currey O’Neil, 1954, p78

[vi] McKay, ibid

[vii] Cantrell, p12

[viii] Palmer, p90

[ix] For more details of Stephens’ life see - Stuart Lee, 'Stephens, Alfred George (1865–1933)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/stephens-alfred-george-8642/text15107, published in hardcopy 1990, accessed online 14 May 2014. This article was first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 12, (MUP), 1990

[x] Cantrell, p18