By DAVID MYTON

The author of the Gospel of Matthew may well have been talking about 19th Century Europe when he wrote “of wars and rumours of wars” in which “nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom”. (Matt 24 6-7)

Armed conflict, revolt and rebellion seemed to be the continent's default mode from at least the early 1800s until 1878 - the year of The Congress of Berlin.

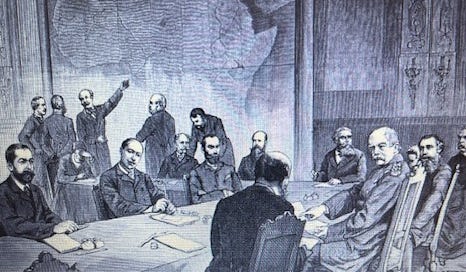

Organised by the remarkable German Chancellor Otto Bismarck, this brought together leaders from across Europe to sort out economic, diplomatic, nationalistic and military issues that simmered across the continent, threatening to spark yet another war.

Diplomats from the “Great Powers” - Russia, Great Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy and Germany - plus representatives from countries including Greece, Serbia, Romania and Montenegro - hammered out a deal that “settled the map of Eastern Europe for some 30 years” and which marked Germany’s emergence “as the predominant power in Europe”. (James Joll, Europe Since 1870. See References below for details of works cited)

The Congress was a watershed in the history of Europe: after years of conflict, revolt and turmoil, peace broke out and was maintained for the next 34 years.

“No European frontier was changed until 1913; not a shot was fired in Europe until 1912 except in two trivial wars that miscarried [between Serbia and Bulgaria 1885, and between Turkey and Greece in 1897], writes English historian AJP Taylor.

“It would not do to attribute this great achievement to the skill of European statesmen. The decisive cause was, no doubt, economic.”

National passions and state rivalries still existed, but now they were no longer intent on fighting each other. The Europeans had discovered something brimming with the promise of riches and power - Imperialism.

In the last quarter of the 19th Century - “The Age of Imperialism - Europe’s great powers competed with each other “to grab territories in the backward, defenceless areas of the world, especially in Africa, the Pacific and South East Asia,” says Taylor.

The imposition of European force and authority on various countries around the world wasn’t new - but in this dawning Age of Imperialism their power had grown in scale and scope.

As Niall Ferguson writes, in the mid-19th Century “Africa was the last blank sheet in the imperial atlas of the world”. The Europeans wanted to make their mark on it.

The British held some African colonial possessions in Sierra Leone, Gambia, Gold Coast and Lagos. However, within 20 short years after 1880 “10,000 African tribal kingdoms were transformed into just 40 states, of which 36 were under direct European control”.

“Never in human history had there been such drastic redrawing of the map of a continent,” Ferguson writes.

By 1897, Britain’s Queen Victoria “reigned supreme at the apex of the most extensive empire in world history”.

In 1860 the territorial extent of the British Empire had covered some 9.5 million square miles; by 1909 the total had risen to 12.7 million, covering some 25 per cent of the world’s land surface - making it three times the size of the French and ten times the size of the German possessions.

“Some 444 million people in all lived under some form of British rule. Not only had Britain led the Scramble for Africa [but also] had been in the forefront of another Scramble in the Far East, gobbling up the north of Borneo, Malaya and a chunk of New Guinea” as well as islands in the Pacific such as Fiji, New Hebrides and the Solomons, says Ferguson.

The key to this expansion in the late Victorian period was “the combination of financial power and firepower”.

But Imperialism wasn’t just a British thing. Most of the European powers wanted in on the action - France, Italy, Germany and Holland, for example, had established colonies overseas while private adventurers from across the continent were also involved.

For example, Leopold II, the King of the Belgians, was a “financial conquistador” who sponsored explorations in the Congo, writes John McManners.

The European “mania for expansion” in the years 1871-1900 saw Britain annex over four million square miles - an area one-third the size of Europe with over 60 million inhabitants; France took more than three million square miles, Germany and Belgium one million each, with Italy snaring a few thousand.

This expansion led to new imperialist rivalries among the great powers “and to the belief that the balance of power had to be regarded as a world-wide question and not one limited to Europe alone”, says James Joll.

“It opened the countries of Africa and Asia to European influence on a far greater scale than ever before, giving their populations a taste of the evils as well as the benefits of European technology, European administrative methods, and European ideas.”

The map of Africa was divided up by the colonising powers to suit their administrative or diplomatic convenience so that in the 20th century “these boundaries often became quite illogically the boundaries of independent states, corresponding to no ethnic or economic reality.”

I plan to examine the Imperialism phenomenon in more detail in future posts.

REFERENCES

Rene Albrecht-Carrie, A Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna, Methuen, London, 1958

Niall Ferguson, Empire. The Rise and Demise Of The British World Order And The Lessons For Global Power, Allen Lane, London, 2000

Harry Hearder, Europe In The 19th Century 1830-1880, Longman, London, 1966

James Joll, Europe Since 1870, Penguin Books, 1983

Wm. Roger Louis, Ends Of British Imperialism. The Scramble for Empire, Suez and Decolonisation. Collected Essays, I B Tauris, London, 2006

John McManners, Lectures On European History 1789-1914. Men, Machines and Freedom, Blackwell, Oxford, 1966

Bernard Porter, Britain, Europe and the World 1850-1986. Delusions of Grandeur (2nd ed), Allen & Unwin, London, 1983

Agatha Ramm, Europe In The 19th Century 1789-1905, Longman, London, 1984

AJP Taylor, The Struggle For Mastery In Europe 1848-1918, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1954

This is a great overview of course and consequences of imperialistic colonisation. It would be interesting to explore further long lasting effect of this process on some of the African nations, for example.