Poetry slam: the amazing 'duel' in verse between two great Aussie bards of the Bush

How poets Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson found fame with rhyme and reason

By DAVID MYTON

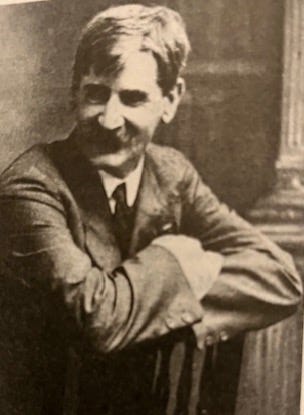

One evening in June 1887 a tall, slim, 20-year-old man with burning brown eyes and a magnificent mustache hurried through the rain-drenched Sydney streets to the George Street offices of The Bulletin.

Summoning all his courage and resolve, he thrust an envelope into the Bulletin’s post box. It contained a poem, signed HAL. It carried his hopes and dreams of being famous one day. A poet, no less.

It was a gamble. Editor JF Archibald was known for his uncompromising and sarcastic manner in The Bulletin’s “responses to correspondents”. One story[1] has it that Archibald had a quick read of the poem and then threw it in the waste basket from which the journalist Fred Broomfield retrieved it, was impressed, and suggested Archibald take another look.

Which he did, and was similarly impressed. Meanwhile Lawson, a man of poor education, inflicted with deafness and currently a house painter and odd-job man, waited, and waited, watching for some hope in the Answers to Correspondents column.

And then, unbelievably, magnificently, there it was in the issue of July 23 1887, the 14 words that changed his life: “HAL: Will publish your ‘Sons of the South’. You have in you good grit!” Almost three months later, on October 1 1887, it appeared in print as ‘A Song of the Republic’:

Sons of the South, awake! arise!

Sons of the South, and do

Banish from under your bonny skies

Those old world errors and wrongs and lies.

Making hell in a Paradise

That belongs to your sons and you.

Lawson was proud of it: “it was my first song and sincere – written by a bush boy who was a skinny city work-boy in patched pants and Blucher boots, struggling on the edge of the unemployed gulf”[2].

Now he was on his way and he had The Bulletin – and Archibald - to thank for it.

Just a few months later, at Christmas 1887, Archibald published another Lawson poem – Golden Gully …

No one lives in Golden Gully, for its golden days are o’er,

And its clay shall never sully blucher-boots of differs more,

For the diggers long have vanished – nought but broken shafts remain,

And the bush, by diggers banished, fast reclaims its own again.

Now, when dying Daylight slowly draws her fingers from the ‘Peak’

The Weird Empress Melancholy rises from the reedy creek

On December 22 1888 Archibald went one step further – he published all six chapters of one of Lawson’s short stories ‘His Father’s Mate’:

It was Golden Gully still, but golden in name only, unless, indeed, the yellow mullock heaps, or the bloom of the wattle-trees on the hillside gave it a better claim to its title. But the gold was gone from the gully, and the diggers were gone, too …

Archibald liked the poet-writer, saw something profound: he recalled the day when “I first beheld the burning eyes of Henry Lawson”[3] and he praised and encouraged him – “You’ve got talent …” and was “nice, understanding” showed “great compassion”, was “kind and considerate”.[4]

Archibald applied much of his editing genius to Lawson’s work, smoothing it out, taking away the rough edges.

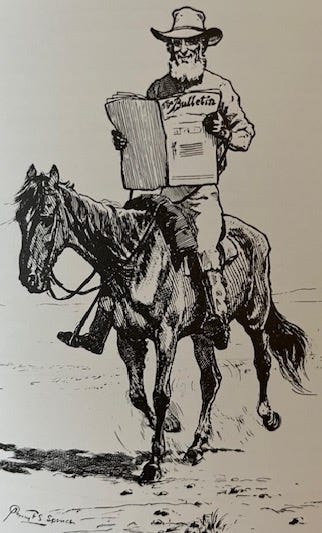

Lawson was to become the epitome of The Bulletin spirit, especially in the revered manner it regarded the new nationalistic Australia and the world of the Bush.

The literary critic A G Stephens acknowledged Lawson’s ability to “represent glimpses of life with remarkable truth, strength and sympathy. His writings in verse and prose … abound with little nuggets of observation and insight; bright with simple pathos, natural humour, and tense vehement expression”.[5]

But Lawson began drinking heavily, his alcoholism impairing not just his poetry but also his relationships. He died a lonely death in September 1922, but with a legacy of some of the best verse and story writing in Australian history: two examples stand the test of time – the poem ‘Andy’s Gone With Cattle’ and the brilliant short story ‘The Drover’s Wife’.

Belatedly, he gained official recognition for his talent and for his contribution to Australian letters - the Commonwealth Literary Fund granted him a £1 a week pension from May 1920, just two years before he died. He was also given a state funeral on September 4 1922.[6]

There was someone else, however, who had insights into life in the Australian bush, but from a different angle - where Lawson saw penury and misery, he saw adventure and joy. He also owed a lot to J F Archibald.

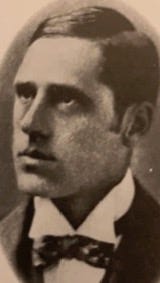

His name was Andrew Barton Paterson, known from 1889 as The Banjo.

‘Banjo’ Paterson was born in 1864 at Narrambla near Orange, New South Wales, later moving with his family to Illalong in the Yass district. Unlike Lawson, he had a happy upbringing, although an injury to his right arm left him with one limb slightly shorter than the other[7]. He enjoyed a bush boyhood, watching

“… The exciting traffic of bullock teams, Cobb & Co. coaches, drovers with their mobs of stock, and gold escorts became familiar sights. At picnic race meetings and polo matches, he saw in action accomplished horsemen from the Murrumbidgee and Snowy Mountains country which generated his lifelong enthusiasm for horses and horsemanship and eventually the writing of his famous equestrian ballads.”[8]

He was clean cut, handsome, industrious and optimistic. He was gifted with the ability to write well, and he worked hard at his craft. By profession he was a solicitor, qualifying in August 1886.

He was as different from Lawson as it is possible to be – with the exception that both of them loved writing about Australia. (The nickname Banjo incidentally was borrowed from a station racehorse with the same moniker).[9]

Another thing they had in common was that each owed much of their success to J F Archibald, editor of The Bulletin.

Paterson’s first poem in The Bulletin was ‘El Mahdi to the Australian Troops’, published on 22 February 1885[10]:

And wherefore have they come, this warlike band,

That o’er the ocean many a weary day

Have tossed; and now beside Suakim’s Bay,

With faces stern and resolute, do stand,

Waking the desert echoes with the drum –

Men of Australia, wherefore have ye come?

On August 22 1886 Archibald wrote to Paterson asking if he would pop in to the office so they could talk “about a lot of things”. He gave some information regarding what The Bulletin was about, adding that its chief policy was to “howl for the undermost dog”.

Archibald asked for future contributions and praised Paterson, saying “Your ‘copy’ is on the average clear enough to be dreamt on by good sober printers in holy dreams of heaven”.[11] There followed a raft of poems and stories published in The Bulletin and then on December 21 1889 there appeared a poem that cemented Paterson’s reputation … ‘Clancy of the Overflow’:

I had written him a letter which I had, for want of better

Knowledge, sent to where I met him down the Lachlan, years ago,

He was shearing when I knew him, so I sent a letter to him,

Just “on spec”, addressed as follows: “Clancy of The Overflow”.

And an answer came directed in a writing unexpected,

(And I think the same was written with a thumbnail dipped in tar)

‘Twas his shearing mate who wrote it, and verbatim I will quote it:

“Clancy’s gone to Queensland droving, and we don’t know where he are.”

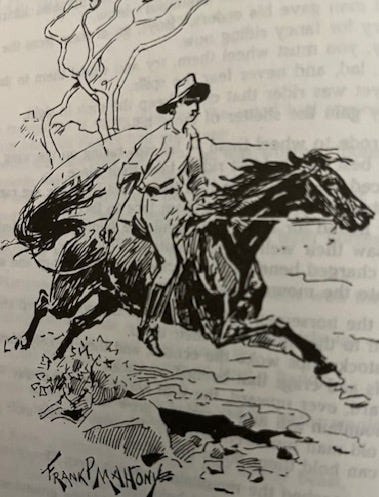

There followed more poems, more stories, and on April 26 1890 The Bulletin published yet another jaw-dropper: ‘The man from Snowy River’.

There was movement at the station, for the word had passed around

That the colt from old Regret had got away,

And had joined the wild bush horses – he was worth a thousand pound.

So all the cracks had gathered to the fray.

All the tried and noted riders from the stations near and far

Had mustered at the homestead overnight,

For the bushmen love hard riding where the wild bush horses are

And the stockhorse snuffs the battle with delight.

There was much more to come from Paterson, as there was from Lawson. Of course, they weren’t the only two writers enlivening The Bulletin’s pages, and they both wrote for other journals also. But Lawson and Paterson stand out. The Bulletin gave them their initial platforms, and out of its pages came forth the Bush Ballad, a distinctively Australian contribution to literature. (Paterson also wrote a ballad to bring a tear to most Australian eyes: Waltzing Matilda, first composed in 1895 and then published in 1903 – as sheet music).

Whereas Paterson wrote of the hardships that all had to share in pioneering the land “he rarely expressed resentment against privilege. His writing reflected the interest of the independent, struggling man pitted against nature but not that of the embittered man struggling against a landed master … adversity was not overwhelming – rather it was to be accepted as part of bush life”.[12] Lawson, however, saw an Australia whose “spirit is sensual despair, whose tutelary genius is the siren of the wilderness … his muse is the muse of Flood and Fire; of drought and Death … the wretchedness and the repulsiveness of the starved soul, as of the starved body”[13].

Cunning plan

Now the differences between Lawson and Paterson were not lost on the two men. They’d read each other’s poems and stories in The Bulletin, and despite their differences actually liked each other. At one stage Paterson used his legal skills to help Lawson to draw up contracts with publishers[14]. Said Paterson:

“… Lawson was a man of remarkable insight in some things and remarkable simplicity in others. We were both looking for the same reef, if you get what I mean, but I had done my prospecting on horseback with my meals cooked for me, while Lawson had done his prospecting on foot and had to cook for himself …”[15]

So as brothers in verse they came up with a cunning plan. Lawson suggested they write against each other in poetry: Paterson would write something, Lawson would criticize it, and so on. It would be Lawson’s grim pessimism versus Paterson’s rollicking optimism. And one other thing these brothers in verse were reckoning on: they were not on retainers, but paid only on what was published. If it all worked to plan, it should be a nice little earner.

Lawson’s first offering was ‘Up the Country’ in which he has been looking for sunlit plains, shining rivers and other pleasant scenes spoken of by “southern poets” (ie Paterson). Alas, all he has found are burning wastes of barren soil and sand, where the Bushman sees “Nothing … but the sameness of the ragged stunted trees …

Treacherous tracks that trap the stranger, endless roads that gleam and glare,

Dark and evil looking gullies, hiding secrets here and there!

Dull dumb flats and stony rises, where the toiling bullocks bake,

And the sinister goanna, and the lizard and the snake.

Going up the country

Paterson responded in ‘In Defence of the Bush’, noting that Mr Lawson is back from up country …

And you’re cursing all the business in a bitter discontent;

Well we grieve to disappoint you, and it makes us sad to hear

That it wasn’t cool and shady – and there wasn’t plenty beer,

And the loony bullock snorted when you first came into view;

Well, you know it’s not so often that he sees a swell like you …

Lawson’s answer to Banjo came in ‘The City Bushman’, in which he borrows the rhythms of ‘Clancy of the Overflow’ to ask

Would you like to change with Clancy – go-a-droving? tell us true,

For we rather think that Clancy would be glad to change with you,

And be something in the city; but twould give your muse a shock

To be losing time and money through the foot-rot in the flock,

And you wouldn’t mind the beauties underneath the starry dome

If you had a wife and children and a lot of bills at home

Paterson’s ‘An Answer to Various Bards’ published by The Bulletin on October 1 1892, states that before they curse the bush Lawson and his kind “should let their fancy range, And take something for their livers, and be cheerful for a change” …

And a bushman never struck me as a subject for “the tomb”

If it ain’t all “golden sunshine” where the “wattle branches wave”,

Well it ain’t all damp and dismal, and it ain’t all “lonely grave”.

And, of course, there’s no denying that the bushman’s life is rough,

But a man can easy stand it if he’s built of sterling stuff…

Lawson hit back with a sort of manifesto in The Bulletin of November 18 1893, ‘Some Popular Australian Mistakes’ - 23 points about what inland Australia is really like, not what people believe it to be. For example, a shearing shed “is not what city people picture it to be – it is perhaps the most degrading hell on the face of this earth”:

“In conclusion. We wish to Heaven that Australian writers would leave off trying to make a paradise out of the Out Back Hell … What’s the good of making a heaven of a hell when by describing it as it really is we might doi some good for the lost souls there?”

Numerous other poets, writers and correspondents joined in the debate, which was never resolved one way or another. What it did do was help to push up the circulation of the newspaper. Paterson died in 1941. In the words of Clement Semmler:

“By the verdict of the Australian people, and by his own conduct and precept, Paterson was, in every sense, a great Australian. Ballad-writer, horseman, bushman, overlander, squatter—he helped to make the Australian legend...”[16]

[1] Peter Kirkpatrick, The Sea Coast of Bohemia, Literary Life in Sydney’s Roaring Twenties, UQP, St Lucia 1992, p34

[2] Henry Lawson, ‘A Fragment of Autobiography’, in Leonard Cronin (ed), Henry Lawson, A Camp-Fire Yarn, Complete Works 1885-1900, Redwood Edition, Lansdowne Publishing Pty Ltd, 1984, p34

[3] J F Archibald, ‘The Genesis of The Bulletin’ (Being the memoirs of J F Archibald), The Lone Hand, Sydney, May 1907, p53

[4] Manning Clark, Henry Lawson. The Man and the Legend, Melbourne University Press, 1995, pp 102, 105,115, 148

[5] Leon Cantrell (ed), A.G. Stephens: Selected Writings, Angus & Robertson, 1978, p251

Brian Matthews, 'Lawson, Henry (1867–1922)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lawson-henry-7118/text12279, published in hardcopy 1986, accessed online 10 April 2014.

This article was first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 10, (MUP), 1986

[7] Rosamund Campbell and Phillippa Harvie, ‘General Introduction’ in Singer of the Bush. A.B. ‘Banjo’ Paterson. Complete Works 1885-1900, Redwood Editions, Victoria, by arrangement with Lansdowne Publishing Pty Ltd, Sydney, 2000, pxi

[8] Clement Semmler, 'Paterson, Andrew Barton (Banjo) (1864–1941)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/paterson-andrew-barton-banjo-7972/text13883, published in hardcopy 1988, accessed online 10 April 2014. This article was first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 11, (MUP), 1988

[9] Singer of the Bush, pxi

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] R M Younger, Australia and the Australians. A New Concise History, Humanities Press, New York, 1970, p386

[13] Stephen Alomes and Catherine Jones, A Documentary History: Australian Nationalism, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1991, p73

[14] Semmler, op cit

[15] Paterson newspaper interview (Sydney Morning Herald 1939) in Campbell and Harvie, op cit p xxiv

[16] Semmler, op cit