Rambling On with History Explored: Does the past have a Sound and a Smell?

A new weekly column from me about history stuff that I've been thinking about

By DAVID MYTON

Dear Subscribers - This is the first in what I hope will be a regular history column from me around Sunday-Monday each week. It’s going to be a bit different from my usual referenced, research-essay style. Instead, I’m just going to ramble on: what I’ve been thinking about and/or reading in recent days. This is the first and only draft. Please feel free to chip in with (preferably nice, informative) comments.

Anyway, here goes.

What I’ve been thinking about this week is: What might History SOUND and SMELL like?

Around 10 years ago or so I was taking a Spring break in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, Australia. This is a gorgeous area, dotted with pretty towns and villages set amid forests, hills and dales, streams, waterfalls, views … the whole nature-at-its-best deal.

Early one evening I decided to take a casual walk (no special equipment) through one of the said forests. I got lost. I had wandered off the path with the idea of walking along the bank of a story-book-beautiful stream. I plodded on for a few miles as it twisted and turned down gentle tree-studded slopes before I decided to turn back. But everything looked different. The sun was going down, shadows lengthened … suddenly it was dark.

And then it started: the spooky noises. Leaves were rustling even though there was no breeze for them to rustle in.

Something that sounded like a dying elephant was making a loud honking noise; something else was squawking; slithery snakey sounds emanated from the bush; and there were other sounds that couldn’t possibly come from any known animal.

Could they be the spirits of the dead, I wondered, even though hitherto I hadn’t believed in the spirits of the dead. Right then, gripped by mounting panic, I was prepared to believe anything.

Long story short, I eventually stumbled on a track that led me out of the forest and back to the world of houses, cars, and roads with helpful signs that pointed me back to where I started.

It made me think … what would it have been like to live in, say, 11th century northern England (the country where I born and grew up)?

The world would have seemed animated by a host of imps and spirits, the night sky would have been darker because there was no radiant light from big cities; the stars and planets (even though you didn’t really know what stars and planets were) would glow and blink and every now and then a comet with a fiery tale would appear and scare the shit out of everyone, and we would all pray that it would go away, and it did, so our prayers were answered.

Belief in the God of the priests and pious would be completely, unquestionably rational. You knew that ghosts and malevolent spirits dwelled in the woods and in the streams. For sure, you needed the Almighty’s help.

Now here’s a suggestion: Wherever you are, go outside and just listen.

I live in a quiet suburb of Sydney, a city of over five million people. More or less any time of day I can hear a low background hum of cars, trucks, motorbikes, and planes overhead going into land at Sydney Airport.

What would I have heard, say, 500 years ago? … Perhaps bird song, snakes slithering in the bush, some marsupial bouncing around, rain falling into the vegetation, thunder, breezes blowing through the trees. How could I be certain it was a breeze? 500 years ago I might think it was some kind of spirit … could I tell the difference?

If there was a big storm, would it be a portent of something supernatural about to happen? I don’t know!

I tracked through my copy of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles to see if I could find the scribes’ reactions to natural phenomena. (I should say that across the centuries the chroniclers also recorded much human-on-human violence, wars, battles, sackings etc., meted out by human beings to other humans). Here’s just a few entries from the chroniclers (with date of Year):

540 … the sun darkened and “the stars showed fully nearly half an hour past nine in the morning”

664 - The sun darkened and “there was much pestilence on the island of Britain”

763 - “This was the year of the hard winter”

798 - Cenwulf, king of Mercia, ravaged the Kentish people … Praen their king “had his eyes put out and his hands cut off” (nothing to do with nature, but pretty typical of human behaviour every year)

975 - Then was shown up in the skies that star which men wise in spirit in the craft of science call the comet … The Ruler’s wrath was throughout the peoples, widely shown, hunger on earth

1014 - On Michaelas’ Eve came the great sea flood widely through this land, and it ran farther than it ever had, flooded many towns, and drowned countless human beings

1044 - There was a very great famine in England, and corn dearer than than anyone ever remembered

1046 - After Candelmas came the hard winter with frost, snow and all bad weather, such that no man alive might remember so hard a winter as that was, in human death and cattle death, and birds and fish died in the great cold and famine

1060 - There was a great earthquake on the day of the Translation of St Martin

1078 - The moon darkened three nights before Candlemass. This year was the dry summer. Wildfire came in many shires and burnt down many towns, and also burnt down many strongholds

1087 - Then fell a very heavy and very pestilential year in this land:

“Such disease with fever came among men so severely that many died in this evil. Then came a very great famine all over England so that many hundreds of people died a wretched death through hunger

Alas, how pitiful a time was that, when wretched men lay fevered full near to death … Who cannot pity such a time? Oh who is so hard-hearted that he cannot weep for such misfortune? But such things come to pass for the sins of the people that they will not love God and righteousness.”

I got a bit off track with all that, but the point is that death and disease wouldn’t be attributable to viruses and bacteria, because no-one knew about them; rather, it would be the mystery of God’s will, or for punishment for sins, or for the learning of a lesson.

People back then would be surrounded by sounds (but not our modern-day sounds) … birdsong, breezes in the trees, the crashing of waves, wildfires raging, dogs barking, people singing/laughing/praising/screaming/pleading/begging.

We might think: Was our current bad luck and trouble that comet’s fault? Did it send the famine? Did the darkening of the Sun make everyone ill? Did that shooting star spread the plague? Who knew?

That’s not to say that people were entirely hopeless and helpless. Many survived through good luck or skill in planting and seeding in the right place at the right time; or being strong and able to fight ferociously. Or that God did eventually answer their prayers.

Maybe He would listen to the 10th century Ploughman’s Prayer:

Earth, Earth, Earth! Oh Earth our mother!

May the all-wielder, Ever-Lord grant thee

Acres a-waxing, upwards a-growing,

Pregnant with corn and plenteous in strength.

(- cited in Eileen Power, Medieval People: A Study of Communal Psychology, London, 1937)

For sure, it was not our world of doctors and hospitals, emergency services, antibiotics and vaccines, planes and trains and trucks and boats and buses, and a scientific, rational mindset.

What did this younger, pre-industrial, world smell like? … the scent of blossom, flowers and herbs, the freshness that follows after rain. The aroma of earth and grass and leaves.

And above all … the smell of shit and piss.

In early medieval villages and towns, toilets were sited at or near the backdoor of most houses “with no apparent concern for the odor, nor the flies that had so little distance to travel from the refuse to the food that people ate”, (R Lacey & D Danziger The Year 1000. What Life Was Like At The Turn Of The First Millennium, 1999, p120):

“There was no awareness of how disease can be spread by bacteria, and people took it for granted that their bodies should provide hospitality for parasites that ranged from relatively inoffensive whipworm to the more sinister maw-worm, which could grow as long as 30cms, migrating all over the body, including lungs and liver … maw-worm could emerge unexpectedly from any orifice, including, most alarmingly, the corners of people’s eyes.” (ibid)

When the priests and the monks came by with their Christian Gospels (Godspell, the good news) the miracles of Jesus would be totally, utterly believable, literally, no question. Resurrection? No problem. Healing the sick and raising the dead? Of course. Walking on water? Too easy. The Old Testament great flood, the parting of the sea, the writing on the wall, and so on … what’s to doubt?

The human race survived, it learnt incredible, amazing things, and we modern folk are the beneficiaries of their wisdom.

I’ll be back with another Ramble next week. Cheers!

That was a really enjoyable read. More like that would be very welcome.

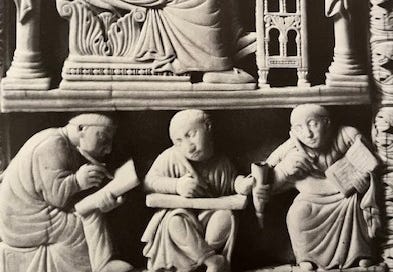

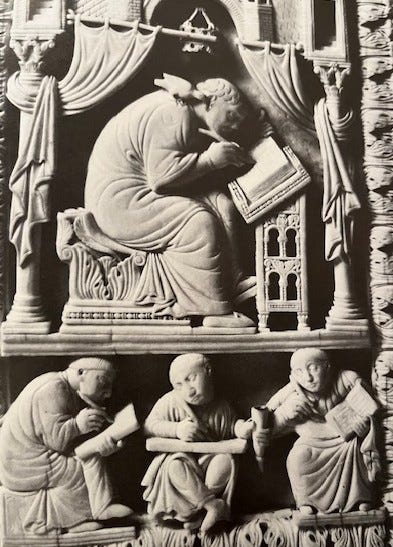

Love your focus on emotions! It is no wonder that the medieval age is also known as the age of emotions. There's a very niche academic research into medieval emotions! Surprised about it! @matthewlyons wrote about the iconography of emotions in early churches! Also Kate susong! https://open.substack.com/pub/mathewlyons/p/nottingham-alabaster-objects-of-strangeness?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=l5w4y