By DAVID MYTON

A pervasive unease mixed with bright flashes of promise and optimism gripped many people in England as the 19th century drew to its close. There were exciting public and private debates about religion, art, science, progress, empire, evolution, and sexuality. The previously unspeakable was being spoken.

At the same time a gnawing social anxiety inhabited the minds of many. It was a modern malady: Angst … “the common denominator of belief and unbelief”, writes Gertrude Himmelfarb. (See References below for details of books cited).

Where would it all end? Nobody knew. But many thought it wouldn’t end well.

Welcome to the Victorian Fin de Siecle.

“Civilisation anywhere is a very thin crust,” wrote John Buchan. “A combination of multitudes who have lost their nerve and a junta of arrogant demagogues has shattered the comity of nations. The European tradition has been confronted with an Asiatic revolt, with its historic accompaniment of janissaries and assassins.”

Queen Victoria had been crowned on June 20, 1837 and reigned until her death in January 1901 - a whopping 64 years, an anchor of familiarity and stability in an otherwise rapidly changing world.

The last 20 years of the 19th Century and the first 10 of the 20th Century was a time of enormous scientific and cultural debate concerning the future of civilisation and the human race … would it be a time of progress or would mankind degenerate as the planet died beneath its feet?

The Victorians had witnessed or otherwise participated in a destabilising industrial revolution, a demographic transition from the countryside to pestilential cities where many of their denizens lived in poverty and filth. They had fretted over Thomas Malthus’s prognostications about the perils of over-population and laissez faire competition, been perturbed by the new Biblical Criticism (what do you mean God didn’t dictate the Scriptures?), and what on Earth were they to think about the British Empire. Surely it was a good thing … wasn’t it?

And they had been shocked by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution which seemed to take God out of the picture of Creation. In 1893 T. H. Huxley said that evolution was a guide “not to morality but to immorality” … it was the law of the jungle and “put a premium on cunning, brute force, ruthlessness, ferocity … it rewarded the wicked and punished the righteous, it was an unedifying and even horrifying spectacle”. (Himmelfarb, p328)

All of this, and much more besides, characterised the Victorian Fin de Siecle - an epoch of huge change, of endings and beginnings, the “collision between the old and the new, [an] excitingly volatile and transitional period … a time when British cultural politics were caught between two ages, the Victorian and the Modern; a time fraught with anxiety and an exhilarating sense of possibility… [but] haunted by fantasies of decay and degeneration …” write Sally Ledger and Roger Luckhurst.

In this article I’m going to present one case study that reflects many of the fears, anxieties and shocks redolent of the Fin de Siecle.

The Bitter Cry of Outcast London

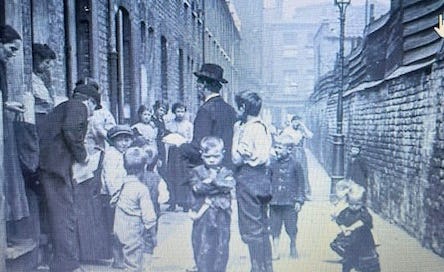

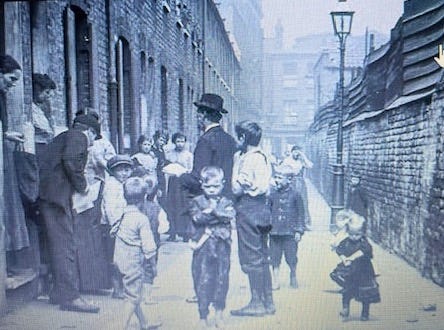

In the 1880s London, England, was a booming city, home to 3.8 million people and a world-leading hub of commerce and industry. It was the place to be if you wanted to make some money and get on in the world.

But there was another side to the city: a dirty downtrodden underbelly of the broke and the broken, the homeless, workhouses, crime and criminals, violence and brutality, a seething mess of poverty and privation - all the things that would shock and dismay “decent” people.

In mid-October 1883 an unassuming, mild-mannered Scottish clergyman, the Reverend Andrew Mearns, published a short report entitled The Bitter Cry of Outcast London: An Inquiry into the Condition of the Abject Poor – a 20-page, one-penny pamphlet that scandalised and shamed much of London society.

Mearns had explored the physical and moral condition of London’s slums, particularly overcrowding and its consequences. He had burrowed beneath the surface to reveal a sordid horror story – shocking and appalling English bourgeois sensibilities with its frank revelations of incest, prostitution, starvation, the mutilation of children, depravity, drunkenness, and disease.

It was all eyewitness material – Mearns was a brave and acute observer, shedding the light on England’s dark side. He says this of the slums:

“Seething in the very centre of our great cities, concealed by the thinnest crust of civilization and decency, is a vast mass of moral corruption, of heart-breaking misery and absolute godlessness. The vilest practices are looked upon with the most matter-of fact indifference.

“The low parts of London are the sink into which the filthy and abominable from all parts of the country seem to flow. Entire courts are filled with thieves, prostitutes and liberated convicts

“Tens of thousands are crowded together in rookeries amidst horrors which call to mind what we have heard of the middle passage of the slave ship.

“To get into them you have to penetrate courts reeking with poisonous and malodorous gases arising from accumulations of sewage and refuse … Walls and ceiling are black with the accretions of filth which have gathered upon them through long years of neglect. It is exuding through cracks in the boards overhead; it is running down the walls; it is everywhere.

“Who can wonder that every evil flourishes in such hotbeds of vice and disease. The vilest practices are looked upon with the most matter-of-fact indifference.

“The low parts of London are the sink into which the filthy and abominable from all parts of the country seem to flow. Entire courts are filled with thieves, prostitutes and liberated convicts.”

Mearns’s fearless revelation of hitherto “unmentionables” such as incest and child prostitution ensured the report grabbed the attention of public and politicians.

Enter the campaigning editor

Crucially, it found its way to the campaigning journalist W T Stead, editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, who had gone in to print with the story on October 23, 1883.

Stead, the son of a Congregationalist minister, saw another big story lurking in Mearns’s report, and that was – Who was to blame? Who owned the slums? What kind of people made a fortune out of the suffering and degradation of their fellow-creatures?

He wrote: “The man who lives by letting a pestilential dwelling-house is morally on a par with a man who lives by keeping a brothel, and ought to be branded accordingly.”

It drew the attention of politicians leading to a huge breakthrough in 1885 - the establishment of the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes chaired by Sir Charles Dilke and including the Prince of Wales.

The Commission’s report has been described as “the most important and comprehensive statement on the reform of public health and housing to emerge from Parliament in the late nineteenth century”.

In 1890 Parliament passed the resultant Housing of the Working Classes Act, which allowed London’s local councils to build houses as well as clear away slums.

And in 1896 London County Council developed the first council housing in Bethnal Green.

The 1900 Housing of the Working Classes Act extended the 1890 Act to places outside London and by the outbreak of WWI about 24,000 units had been built. All local authorities have been required by law to provide council housing since the 1919 Housing Act.

REFERENCES

Gertrude Himmelfarb, Victorian Minds, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1968

Sally Ledger and Roger Luckhurst, The Fin de Siecle. A Reader In Cultural History c1880-1900, Oxford University Press, 2000

John M Mackenzie (ed) Imperialism and Popular Culture, Manchester University Press, 1986

FML Thompson, The Rise Of Respectable Society. A Social History Of Victorian Britain, 1830-1900, Fontana Press, 1988

Ben Wilson, The Making Of Victorian Values. Decency and Dissent in Britain 1789-1837, Penguin Press, New York, 2007

An interesting article David - I think we have some interests in common.