The cherished freedoms promised by Magna Carta may be under threat

Does the Great Charter still have any meaning in a time of acute social change?

By DAVID MYTON

Sir Winston Churchill called it “the most famous milestone of our rights and freedom”; renowned judge and barrister Lord Denning declared it was “the greatest constitutional document of all times - the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot”; and for prominent Australian legal academic and human rights advocate Jillian Triggs it is “one of the defining statements of the rule of law and limits on arbitrary power of the state”.

They are referring to Magna Carta.

Since it came into being on the banks of the River Thames at Runnymede in England on June 10, 1215, the Charter has underpinned the cause of freedom-loving people not just in England but also in countries such as the United States, Canada and Australia.

But does it still have any meaning, any real-world impact in a time of acute social change in the UK and elsewhere?

Mass immigration, de-industrialisation and the advance of post-postmodern dogmas amongst social elites, academics and public intellectuals have created entirely new conceptions of culture, society, free speech, and the meaning of individual freedom.

As former president of the Australian Human Rights Commission, legal academic Professor Jillian Triggs has noted: “Magna Carta is more honoured today as an historical and political symbol, than as a directly applicable source of legal rights and freedoms” pointing out that a High Court Chief Justice had observed … “Magna Carta has given many a plaintiff false hope in litigation before the courts”.

The Great Charter

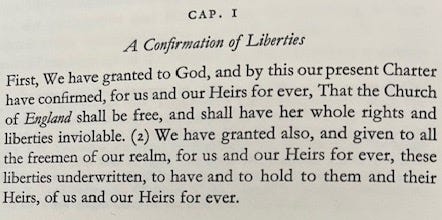

Magna Carta - Latin for Great Charter (in which Great means large) - comprises about 3,350 words, written in Latin.

King John I, who reigned over England from 1199-1216, assented to the Charter which had been demanded by barons and nobility angered by increased taxation and abuse of their traditional privileges.

Not only did the Charter protect their property and rights in their position atop the ancient feudal system, it imposed new limits on the power

of the Crown - including protection from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limits on tax and other feudal payments to the King.

In the words of Winston Churchill … “for the first time the King was bound by the law. The power of the Crown was not absolute”.

King Edward I reissued the Charter of 1225 in 1297 to accommodate a new tax. This version remains in statute today.

Historian David Carpenter argues that the Charter marks a “before” and “after” in English history.

“Magna Carta survived [because] it asserted one fundamental and treasured principle, that of the rule of law. Already by 1300 those from top to bottom of English society saw the Charter as a protection against arbitrary rule ... .”

The Charter set out the “liberties” the King granted his people. However, his subjects would have baulked at such a description, says Carpenter.

“For them the liberties were more in the nature of rights to which they were very much entitled, often by ancient custom.”

The freedom of the individual

Historian Anne Pallister writes that despite numerous attacks and criticisms of the Charter, it continues “to enunciate political and legal principles which are as important today as in the 13th or 17th centuries”.

“The equation of law and liberty, the belief that the law of England protects rather than restricts the freedom of the individual, which is the central feature of the Charter, still lies at the heart of English political thought and practice; and the Charter provides a standard of political ethos against which official action in its effects upon the individual can be measured.”

Magna Carta was not preserved as a museum piece, writes J C Holt, “but as part of the common law of England, to be defended, maintained or repealed as the needs and functions of the law required. It was adaptable. This was its greatest and most important characteristic.”

In a speech in 1946 at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, Winston Churchill stressed the relevance of Magna Carta to a post-war world, asserting that it held the “title deeds of freedom”:

“Freedom of speech and thought should reign; that courts of justice, independent of the executive, unbiased by any party, should administer laws which have received the broad assent of large majorities or are consecrated by time and custom.”

More recently, in a 2002 lecture at Parliament House Canberra, Lord Irvine of Lairg - Derry Irvine - former UK Lord Chancellor from 1997-2003 - declared that the primary importance of Magna Carta “is that it is a beacon of the rule of law … It proclaimed the fundamental nature of individual liberties, notwithstanding that many of the liberties it protected would not find direct counterparts in modern democratic states.”

Magna Carta influenced human rights documents in several connected ways, he argued, referring to these clauses from the Charter:

No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned or stripped of his rights or possessions, or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way, ...except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land. (Clause 39)

To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay, right or justice. (Clause 40)

He added: “These words are the defining statements of the rule of law and limits on arbitrary power of the state … They ring through the centuries and remain the bedrock for principles of justice we struggle to protect in the 21st century.”

As society and culture changes, will they continue to ring?

References

David Carpenter, Magna Carta, Penguin Classics, London, 2015

Winston S Churchill, A History of the English Speaking Peoples (One volume abridgement by Christopher Lee), Cassell, London, 1998

Winston S Churchill, ‘The Sinews of Peace’, speech Westminster College, Fulton, Missouri, March 5 1946 - https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/speeches/1946-1963-elder-statesman/the-sinews-of-peace/

Simon Lee, Lord Denning, Magna Carta, and Magnanimity -https://oro.open.ac.uk/61685/

Lord Irvine of Lairg - The Spirit of Magna Carta Continues to Resonate in Modern Law - https://www.aph.gov.au/binaries/senate/pubs/pops/pop39/lairg.pdf

J C Holt, Magna Carta (2nd ed), Cambridge University Press, 1992

John Hudson, Land, Law, and Lordship In Anglo-Norman England, Oxford Historical Monographs, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1997

Jillian Triggs, ‘Freedom, Parliament and the Courts’, speech to Australian Human Rights Commission - https://humanrights.gov.au/about/news/speeches/freedom-parliament-and-courts-speech-human-rights-dinner

Magna Carta Legacy, US National Archives - https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/magna-carta/legacy.html

Anne Pallister, Magna Carta. The Heritage of Liberty, Clarendon Press, London, 1971

David Starkey, Magna Carta. The True Story Behind The Charter, Hodder & Stroughton, London, 2015

Faith Thompson, Magna Carta, Its Role In The Making Of The English Constitution, Octagon Books, New York, 1972