By DAVID MYTON

Anyone who has flown from London to Sydney knows it’s a grind - 23 boring hours of killing time, dozing, watching movies, eating plane food, and when you do arrive your body aches, and you’re desperate for a sleep and a long shower. Yup, it’s tough.

But it’s nothing compared to doing that journey on a ship in the 19th Century … a voyage undertaken by thousands of men, women and children migrating or exiled to Australia from Britain. Many counted themselves lucky to simply survive.

One mid-19th century ship’s passenger and diarist, Anna-Maria Bright, described the passage as “long, tedious, uncomfortable and often dangerous”.

She added: “It is no use deluding oneself by saying it is not far to Australia - for it is, and tremendously far too.”

Another female traveler bound for Australia around the same time, Jane Roberts, said: “The prospect of the voyage before me was so truly appalling, that at times I completely sunk under the dread of it.”

By around 1880 the voyage to Sydney from London might take between 30-40 days, either via the Cape of Good Hope or through the Suez Canal.

At this time some 1.3 million free immigrants from Britain had sailed to Australia.

By 1885 conditions on board most ships had improved, but it was unlikely anyone would get fat on the diet.

Mandated provisions for each person included two and a half pounds of bread or biscuit, one pound of wheaten flour, five pounds of oatmeal, two pounds of rice, two ounces of tea, half a pound of sugar, and half a pound of molasses … while potatoes “when good and sound” may be substituted for either the oatmeal or the rice.

The typical ship would be made out of iron, have one funnel, three masts (rigged for sail), and a single screw providing a maximum speed of 12 knots. There would be accommodation for 84-1st, 100-2nd and 270-3rd class passengers.

According to Museums Victoria, with the opening of the Victorian goldfields in the 1850s many ship’s captains adopted the new ‘Great Circle’ route in an effort to speed up the journey.

This meant passing far south of the Cape of Good Hope in to catch the ‘Roaring Forties’ – the strong prevailing winds that blew from the west to the east between 40 and 50 degrees south. According to Museums Victoria:

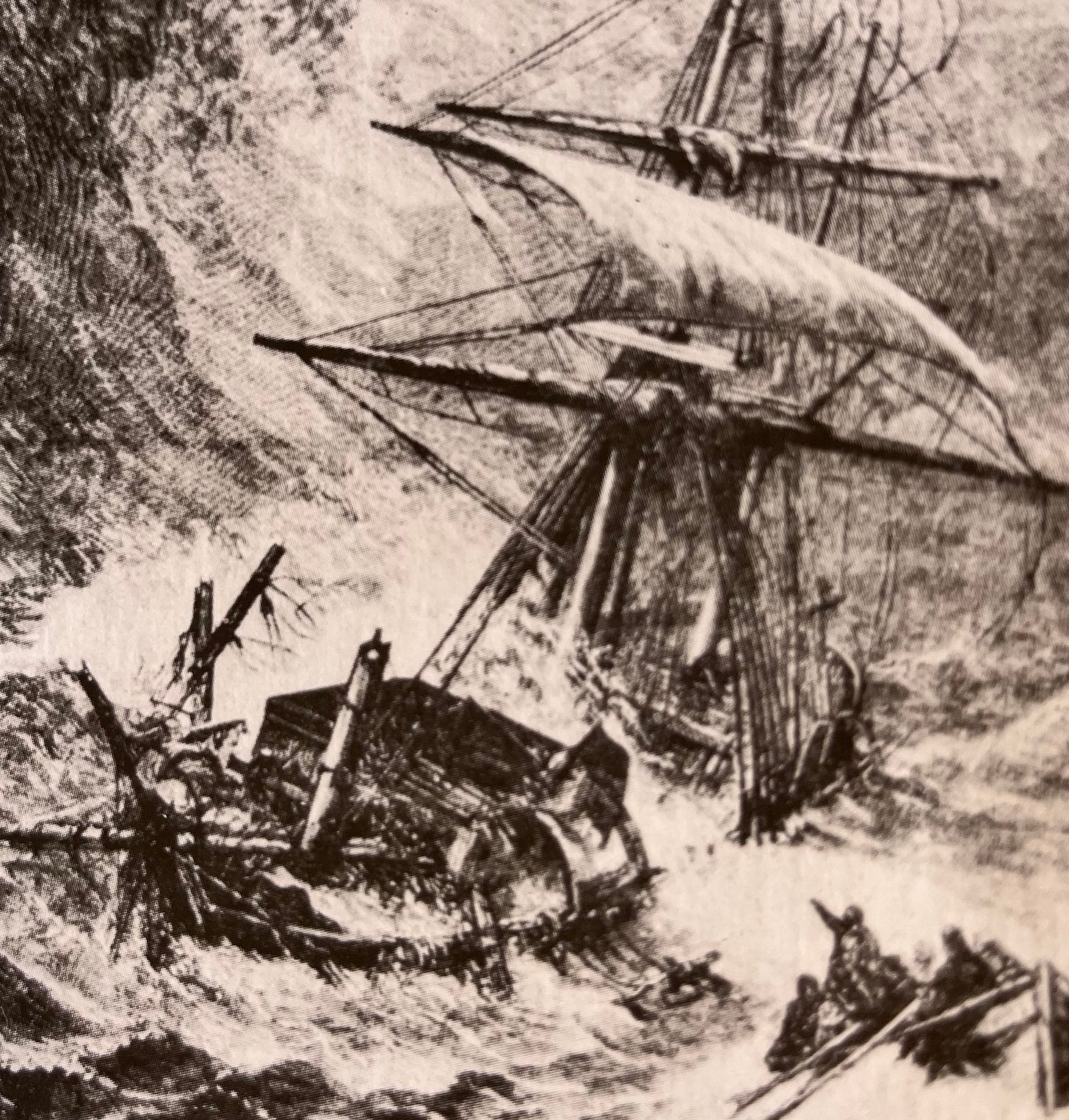

“This route involved enormous risks from drifting icebergs and the wild seas generated by frequent storms. It required exceptional navigational skills, as even the slightest error could lead to disaster. The large number of ships that were lost when navigating the narrow path between King Island and southern Victoria led to the West Coast of Victoria becoming known as the Shipwreck Coast.”

For “steerage” passengers in particular, it says, cramped and unhygienic quarters became worse during great storms in the Southern Ocean.

“At such times, all passengers were confined below deck for days, sick and tossed around, often in complete darkness, and fearing for their lives ...

“Deaths at sea were tragically common. As many as one in five children, and one in 60 adults died on the voyage to Australia. For the burial, the body was sewn into a piece of canvas or placed in a rough coffin (often hastily knocked up by the ship's carpenter) and weighed down with pig iron or lead to help it sink.”

Convicts had it even worse. In the late 18th century Britain decided to send many of its prisoners to exile in Australia - to be employed in hard labour, and ordered to the strictest discipline to reduce them to due obedience - in order to ease pressure on its overflowing prisons system. Around 162,000 convicts were banished to the Down Under jail up to 1840 when the system was abolished.

For example, in December 1796 the Britannia - carrying over 100 convicts - set sail from Cork in Ireland bound for Sydney, arriving 27 May 1797. It immediately encountered “gales, cold, foggy weather and lashing rain”, writes Barbara Hall in her book Death Or Liberty.

During the journey several male prisoners died not as a result of weather, but from being flogged; while also there were a “number of suicides”. In the last few weeks of the voyage to Sydney, the Britannia encountered “hard squalls of hail and snow, fresh gales, and high mountainous seas”.

Some 13 male and two female convicts died during the voyage.

That plane journey is not looking so bad now, is it ...?

REFERENCES

Museums Victoria, Journeys To Australia - https://museumsvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/resources/journeys-to-australia/

Geoffrey Blainey, The Tyranny Of Distance: How Distance Shaped Australia's History, Pan Macmillan Australia, 1967

Barbara Hall, Death Or Liberty. The Convicts of the Britannia, Ireland to Botany Bay, 1797, Sydney 2006.

I found your article interesting. Having been born in Australia with an English father and Australian. I recently did a dna test and found a third cousin in Australia. He had done an extensive family tree and he found that we came from a convict. Having made the trip to England in 1960 I know what rough seas are like, especially The Great Australian Bight. I have wondered what it was like for the convicts to make the trip to Australia.