The making of one of the most popular newspapers in Australian history

Part 4 of this series on the life and career of J F Archibald looks at how he masterminded the rise of the Sydney Bulletin.

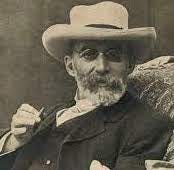

This is the fourth extract of chapters of my work on John Feltham (aka Jules Francoise) Archibald 1856-1919, founding editor of The Bulletin – one of the most popular newspapers in Australia’s history. He was also a successful promoter of Australian literary giants such as Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson. An excellent editor and journalist, his name lives on in the Archibald Prize (awarded annually for Australia’s best portraiture) and the Archibald Memorial Fountain in Sydney’s Hyde Park.

By DAVID MYTON

The year is 1891, the time 11.30am, and the place is Pitt Street, Sydney, New South Wales, specifically No 24 – the offices of the Bulletin, self-styled “national Australian newspaper”, which is busy being put to bed by its team of editors, subs, artists, cartoonists, compositors and printers.

Its Editor, J F Archibald, is set to pull yet another 14-hour day, subbing, editing, making small and large decisions, all in order to get the Bulletin just right for its insatiable readership.

Sales are at 80,000 copies a week – a stunning success in a still sparsely occupied country. Archibald is in the Editor’s chair with William Macleod as business manager. The insightful and scholarly Scot James Edmond has brought his literary acumen to the opinion pages and also applied his immense (self-taught) financial knowledge to business and trade analysis.

The artist Livingstone Hopkins – Hop – “who remained to irradiate the Bulletin with his comic genius over a long period”[i], is busy putting the finishing touches to another brilliant sketch.

Although the formidable literary critic A G Stephens was only to join the Bulletin in 1893, the paper nevertheless had a prodigious literary output largely overseen by Archibald, whose star is on the rise. His searching eye, says a contemporary, is everywhere and nothing escapes him. Every politician is weighed in his scales. His memory, it is said, is such that he can recollect almost every item that has appeared in the Bulletin for years. He wins “the confidence and respect of all who come into close contact with him”.[ii]

He has a weekend cottage by the sea in Cronulla, just south of Sydney. Here he entertains poets, writers and politicians and feed his guests corn beef, potatoes and beer. The artist Norman Lindsay described Archibald as a man “on wires with vitality and interest in the spectacle of life”[iii].

If you lived in Australia and by 1891 had not heard of the Bulletin you would be in a very minor minority. It was known in city and Bush. Politicians, artists, businessmen and bohemians read it. It was “The Bushman’s Bible”, a must read for mining prospectors, squatters, shearers, drovers, landlords and labourers. By 1891 Archibald’s Bulletin was a soaring success. In the words of the prizewinning Australian historian Geoffrey Serle:

“It was rude, slangy, smart, happily vulgar, modern in journalistic style, and above all funny – especially its cartoons. It held an extraordinary combination of extreme attitudes: it was radical, republican, and despised the monarchy and the English ruling classes. It was viciously racist and anti-semitic but also fought against … sectarianism. Its particular strength was a blend of fervent idealism, down-to-earth commonsense and gaiety.”[iv]

The Bulletin’s aims and ambitions were set out on page 3 in the far right column, next to adverts for indigestion cures, electric girdles guaranteed to heal “any case of nervous debility”, and medical, legal and accident insurance for one guinea.

It said: ‘The Bulletin: The Unique Weekly - Australia’s Nonpareil Illustrated Newspaper’ under which it declared that it favoured: A Republican form of government, Payment of MPs, One person, one vote, Complete secularisation of State education, Reform of the Criminal Code and Prison system, and protectionism for Australian-made goods.

It then goes on to denounce, among other things, Religious interference in politics, the Chinese, and Imperial Federation.

It also knows no false modesty, declaring that:

The Bulletin is an aggressive Democratic paper which strives to exclude from its artistically-condensed columns all matter which is not of general human interest. The Bulletin was started 11 years ago with no capital but brains and has become a vast property, because it possesses a vitality lacked by the countless newspaper-ventures in which Australian capitalists have unavailingly spent large fortunes.

The Bulletin’s conductors claim that every progressive paper on the Australian continent has more or less endeavoured to profit from its example and follow its lines. The result of its powerful influence and its unprecedented literary and commercial success can at once be seen by comparing the methods pursued by the Australian daily and weekly press prior to and immediately after the first issue of The Bulletin.

The Bulletin proprietary have spent some thousands of pounds fitting their building with the latest appliances for high-class printing and the production of illustrations [and] with new type of improved legibility on the finest paper, and adorned with sketches from the hands of the ablest and best-paid newspaper artists Australia has ever seen.

The Bulletin is the beacon-fire of national progress: it is the forceful summons to the crusade against the monopolies in land, wealth, power and privilege – the direct cause of half the misery which now afflicts British humanity. Against the claims of avaricious clergy who claim to monopolise salvation, against the dark despotism of grasping plutocrats, and against the exercise of any human authority which has not been granted by the people over whom it is exercised, The Bulletin will fearlessly and ruthlessly contend.[v]

The 1890s was a time of social, political and industrial upheaval in Australia. Over much of the decade loomed a major depression the effects of which were felt in virtually every facet of colonial society. The prosperity that did exist was in large part thanks to British capital investment which, for example, had gone to finance pastoral construction and investment in railways.

However, for various structural reasons, there was little economic growth. The depression was sparked by the collapse of a speculative land boom in Melbourne, a general rise in unemployment, and a fall in export prices. A depression in Britain also had its effect in Australia, in particular in a drop in wool prices. A drought in the mid-1890s also had a deleterious impact. Strikes, lay-offs and other such symptoms of social distress marked this period. It was not until the very late 1890s-1900 that recovery began to kick in thanks, to a large degree, to gold discoveries in Western Australia.[vi]

The Bulletin’s response to the crisis was to call for economic protectionism, by which it meant “duties sufficiently high to practically induce the people of this country to produce for themselves those commodities that could not be made, mined, or grown with a less total expenditure of human energy elsewhere … Our standard of value, and the only one we recognize, is the power of human muscles guided by human brains”.[vii]

There is an anti-capitalist tone in much of the paper’s political commentary (a sly contradiction considering the Bulletin’s outstanding success as a profit-making, capitalist enterprise) and Marx is quoted frequently. Regarding public debt, it is divided between two classes, it says – those who work, the producers, and the people who do not work, the capitalist financiers.

Debt is the peculiar incubus of civilisation “crushing its spirit, destroying its blessings, and marking with the blood of toil every step of progress”. Australia is pursuing the road to destruction: “In a single century, a population of less than 4 millions has piled up a debt of 328 million pounds”. The solution – stop public borrowing, create a sinking fund, conversion and consolidation of debt at lower interest, and the direct and proportional taxation of wealth, particularly unproved land values.[viii]

Capitalists (“the plundering, predatory class”) are excoriated again in an article warning that they are creating profit-making schemes carefully concocted to operate within the sanction of existing codes, so that combinations of capitalists may “plunder consumers by artificially raising the price of commodities by the old device of creating an artificial scarcity by withholding stocks”. Salt, chemicals and labor are examples it gives. [ix]

And so it went, arguing for this case and against that - always provocative; always intelligent. It was stridently opposed to the Boer War, and it was against the British Empire. It wanted to loosen ties with the Old Country and called for an end to “grovelling” which included urging Australians to reject British honours such as knighthoods.

It was against Sir Henry Parkes, five times Premier of NSW, and his Free Trade Party, yet even in its opposition it recognized that the politician with the Father Christmas beard was a great man. Following Parkes’s death on April 27 1896 Hop drew a warm and gently moving picture of a boy (representing NSW) shedding a tear as he closes a thick book titled ‘Parkes’.

It campaigned for more humanity in the legal system and launched blistering attacks against the judge Sir Alfred Stephen whom it believed was too quick to pass the death sentence and corporal punishment. Stephen, it declared, was “a product of the Australian Dark Ages” and a “noose around the neck of Australia”.[x]

It maintained a non-stop lampoonery of religion and its “sky pilots”, that is, priests and parsons.

The Bulletin was in favour of the franchise for women, noting that “female suffrage will leave woman to work out her own destiny”:

“Man, so far, has been a conspicuous failure in almost every capacity, and the doctrine of human equality demands that woman should be allowed the chance to fail along with him in an equal degree. The government of the world has been a long succession of blunders ever since the day when primeval man shed the last semblance of his tail and took his place at the head of creation, and the old traditions have done so little for human happiness that they are not worth regretting.”[xi]

It also advocated for what it called “municipal socialism” in which enlightened Democratic politicians and others in a new local authority run the towns and cities in a caring, purposeful way as opposed to the present model of the typical municipality which is a “neglected, unkempt, and badly-paved place with as much mortgage as it can stagger under – a place which is badly lighted by contract with the gas company, badly drained on no particular principle, scavenged by an unsavoury cart which goes around like a thief in the night, built up on no definite plan, and altogether unprogressive”.[xii]

Taking a different tone entirely, there was an elegiac lament for a bushman whose remains were found near the Clarke River in North Queensland, having apparently starved to death:

“The human tragedy has no grimmer scenes than those daily acted in the vast theatre of the Australian bush. Here the soul’s infinite capacity for anguish is strained through exquisite gradation of torture, till the bars of the body are broken, and merciful Death snaps the thread which binds the Ego to existence … In every nook of the Australian wilderness bleach the bones of Australian pioneers. The dingo and the crow, sole witnesses of their death-struggles, tore the flesh from the shrunken limbs. Sun and rain disintegrated the poor remnants, and left the ruined framework of a man to shock the unthinking traveller, or gradually to be dissipated in the mysterious chemistry of the elements. And the man lived and suffered – to what end?”[xiii]

The Bulletin was against much but what it was for was Australia, which it says calls its people to be patriotic. “Australia is our own country and the pride in united Australia will be the safeguard for our own country.”[xiv]

It strongly supported Federation and argued in favour of the Federal Constitution Bill, warning there “is no possible guarantee that, if Australia loses this chance of union, it will get another”.[xv]

On the death in 1889 of Peter Lalor, one of the leaders of the diggers at the Eureka Stockade, the Bulletin said the day would come when Australians would treasurer such men but first they must be worthy of “the birthright of the free”:

“We must be to our children what the men from all lands, the diggers of the fifties are to us – a pattern and a model of courage and independence, exemplars to all true men who may come after us, to all who love honour more than they fear death, to all who would rather be free in Hell than enslaved in Heaven, to all who would rather bend the head to a monarch’s curse than bend the knee for a serf’s badge of knighthood.”[xvi]

The Bulletin reflected many attitudes of the time such as a pervasive racism, based on contemporary Social Darwinism that saw the “white man” as superior to other peoples.

When the Bulletin proclaimed Australia for the Australians, it meant white people and, particularly, those of British and Irish background. It did not like “foreigners”, including not the least “white foreigners” (Europeans). The thrust of the Bulletin’s arguments against Chinese, Europeans and other peoples centred on economic protectionism as opposed to free trade: “We object to the Chinese … because they are producers and not consumers – because they make money and do not spend it … The man who produces wealth and consumes very little is not to be held up as a model for imitation, but is rather a danger to the community.”[xvii]

The Bulletin took seriously many topics but it was not just a “think-piece” paper. Over the 1890s, for example, it maintained a gallery of short, sharp, snappy paragraphs of amusing, informative and sarcastic tone. They dealt with male-female relations, for example, especially in its numerous cartoons. The mores of 19th century romance were reflected in its columns, as were the experiences of shoe-shine boys, parsons, politicians, drovers and sundry country folk.

As we will see in the next extract the Bulletin, guided by Archibald at his peak, also made an enormous contribution to Australian literature.

[i] Vance Palmer, The Legend Of The Nineties, Currey O’Neil, South Yarra, 1954, p86

[ii] ‘The Sydney Bulletin. Its Clever Editor. A Character Sketch’, in Warnambool and District Newspaper Cuttings, pp68-69, cutting dated February1 1894, held in Mitchell Library, Sydney

[iii] Quoted in Douglas Stewart, Writers of The Bulletin, 1977 Boyer Lectures, Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney, 1977, p13

[iv] Geoffrey Serle, From Deserts The Prophets Come. The Creative Spirit in Australia 1788-1972, Heinemann, Melbourne, 1973, p60

[v] The list here is edited. The full list, which ran through most of the 1890s, can be seen for example in the issue of March 7, 1891

[vi] W.A. Sinclair, The Process of Economic Development in Australia, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne, 1992, pp126-152 passim

[vii] ‘The Ethics of Protection’, Bulletin, May 21, 1892, p5

[viii] ‘The Divinity of Debt’, Bulletin, June 16, 1894, p4

[ix] Untitled par Bulletin, September 21, 1895, p7

[x] ‘Mary Brownlow and Her Judge’, Bulletin, November 3, 1894, p6

[xi] ‘The Great Woman Question’, Bulletin, March 9, 1889, p4

[xii] ‘Municipal Socialism’, Bulletin, June 22, 1895, p6

[xiii] ‘Dead in the Bush’, Bulletin, October 13, 1894, p6

[xiv] ‘For Australia’, Bulletin, June 4, 1898, pp6-7

[xv] ‘The Case for the Bill, ibid, p6

[xvi] ‘The Republic – Not the Dominion’, Bulletin, November 30 1889, p4

[xvii] ‘A Lesson From The Leper’, Bulletin, October 12, 1889, p4