The man who predicted the horrors of World War One ... and was ignored

Ivan S Bloch wrote in 1899 that smokeless powder, bolt-action rifles, new machine guns and powerful artillery had sparked a revolution in modern warfare that no-one had noticed.

By DAVID MYTON

What comes to mind when the words World War One are mentioned? Let me guess - the ghastly nightmare of trench warfare, futile infantry advances across no man’s land, hellish artillery bombardments, sinister clouds of poison gas, rattling machine guns, countless dead and wounded, all located in the mud-and-blood hellscape of the Western Front.

We know about this horror story because it happened and has been recounted many times in countless books and films. But it was all new to the people of the time in 1914. It was a shocking surprise.

But one man had seen it coming - in fact, he predicted these battlefield horrors some 16 years before it all kicked off. He wrote a book about it, more or less describing how World War One would play out.

Did anyone pay attention? Not really.

So this book I'm talking about, published in 1898, was titled The War of the Future In Its Technical Economic and Political Relations written by the Polish banker and economist Ivan S Bloch.

An abridged version of the book titled Is War Now Impossible? was also published in London in 1899, and was energetically publicised by the renowned London newspaper editor and public figure WT Stead. I've put a link below online to that book where you can read it in PDF.

Basically Bloch contended that the invention of smokeless powder, quick-firing bolt-action rifles, deadly machine guns, and powerful, accurate, artillery had sparked a great revolution in modern warfare.

Bloch argued that a big European war would quickly get locked into a stalemate due to the technical developments of weapons and the ability of modern states to harness all the available political and economic forces to continue fighting.

And the victor would suffer almost as much as the vanquished.

Bloch writes that for most of the 19th century, battlefields were no larger than the exercise grounds of a brigade - but they would be “unfathomably huge” in the war of the future.

“The most powerful man will not be able to embrace and combine all the details, requirements and circumstances of such an immense field,” he wrote.

It would be extremely difficult to overcome the resistance of infantry in sheltered and dug-in positions. What he called “the zone of deadly fire” would be much wider than before. Battles would be tougher, bloodier and prolonged.

The great (in my opinion) British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, who served in World War One as a junior officer - and was seriously wounded - writes in his book A History of Warfare that Bloch’s warnings were largely ignored by Europe’s military commanders because Bloch was not professional soldier - so what would he know?

Bloch argued that Europe had no generals experienced in leading massive armies, and no experience of keeping them supplied with enormous amounts of ammo and provisions.

The commander incapable of dealing with such complex problems would sustain tremendous losses.

Armies were now confronted with an awful phenomenon, he said. They were wedded to the idea of the superiority of offensive action; but meanwhile, such strong defence positions had been created which would blunt most attacks.

“The war of the future will be a struggle for fortified positions and for that reason war must be prolonged,” Bloch wrote.

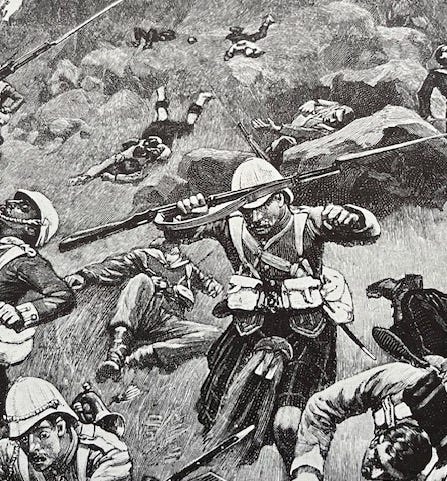

The British Army had actually been given a foretaste of what was to come in World War I at the Battle of Spion Kop in South Africa in January 1900.

A dug-in Boer unit situated on higher ground and armed with German-made bolt-action, magazine-fed Mauser rifles, inflicted grievous casualties on a British force almost devoid of cover.

The Brits were armed with breech-loading, single-shot Martini Henry rifles, and would have been dressed in easy-to-see vivid scarlet uniforms.

Montgomery noted that Spion Kop had been called the “supreme day in the history of the rifle”.

Having learned a painful lesson, though, the British set about producing their own bolt-action rifle – the great Lee Enfield with its sustained 15 rounds rapid (or mad minute) from each soldier. This made such an impression on the Germans at the Battle of the Marne in 1914 the many thought they were being fired on by multiple machine-guns.

Indeed, it was these early actions on the Marne that saw the Germans dig in under fire from these blistering rifle attacks - and they hardly moved for the next three years or so.

World War One was unlike any before it in the scale, complexity, constantly developing technology, automatic weapons, aircraft, tanks and unprecedented large and well-equipped armies.

The top brass didn’t come out of it looking good. Monty, who served as a junior officer in World War One, was also seriously wounded in that conflict.

He had some very deep concerns about the quality of the British Army’s senior staff.

“A remarkable and disgraceful fact is that a high proportion of the most senior officers were ignorant of the conditions in which the soldiers were fighting,” he said.

“The quality of the men who had to do the fighting contrasts with the poor quality of their generals,” he wrote.

Bloch said that the modern war would be one in which every clash with an enemy would be more threatening and every mistake, every hesitation, would have much more serious consequences than in the past. It would be hell for the modern soldier.

I think one of the reasons Bloch’s book didn't fully capture the imagination of its intended audience is that he thought all these new developments in weaponry and technology would make war literally impossible in future.

People would have to be mad to fight in wars because they would be would be unwinnable, he concluded.

Maybe he was close to the truth with that.

REFERENCES

I. S. Bloch, Is War Now Impossible. Being An Abridgement of ‘The War of the Future in its Technical, Economic and Political Relations’, Grant Richards, London, 1899 - https://archive.org/details/iswarnowimpossib00bloc/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater

Field-Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, A History of Warfare, Collins, London, 1968

It's interesting how sometimes it takes an outsider to state the obvious facts that people within that particular field have institutional incentives to ignore or not perceive. A general who wants to make a career amongst other generals needs to think in terms of finding solutions to problems. Making dire predictions about how horribly everything is going to fall apart once the war starts will not help you get promoted. In that way, sometimes the expert is precisely the kind of person who shouldn't be listened to.

I do think, though, that the offense vs. defense narrative misses the point a bit. Reading accounts of what it's like sitting through an artillery barrage prior to an assault makes me wonder how it was possible for those trenches to be held at all: imagine enduring hours of the closest thing to hell imaginable, with no sleep, no food, no contact with the world outside your bunker, and no relief from the deafening noise, trying to stop that one guy who's dangerously close to losing his mind completely from running out the door and getting annihilated, and then, the moment the barrage is over, you have to run outside, throw yourself down behind what little "cover" remains and somehow fend off a wave of soldiers who are all rested, fed, and armed with grenades. Then, if you win, you have to immediately counterattack without the luxury of a preparatory barrage, or even a moment to catch your breath. It really isn't surprising at all that there were quite a few times when the defenses did fail catastrophically.

I think a better way to understand WW1 is in terms of battlefield density. WWI's battles took place in a very compressed space, where there was almost no way to avoid direct confrontation with the enemy. Compare this with WWII, which was characterized by air power (the battlefield expanding upward) and vast movements of armoured columns striking at points of weakness. This makes it easier for commanders to leverage their strength against the enemies weakness, leading to much more movement and dynamism. This obviously favors well-coordinated offensives, but a stupid offensive can fail with even more significant negative consequences for the attacker than would have been the case in WWII.

An interesting thing is that Engels, in the early 1890s, also observed that thanks to the growth of discrepancy between government forces and insurgents, the days of the barricade was gone, as in these conditions so long as the army was willing to follow its orders, the insurgents resisting was simple suicide.