The tragedy of Rosa Frankenstein: lured into marriage by fake French Jew newspaper boss

She sailed from London to Sydney hoping for love and happiness. It was not to be

By DAVID MYTON

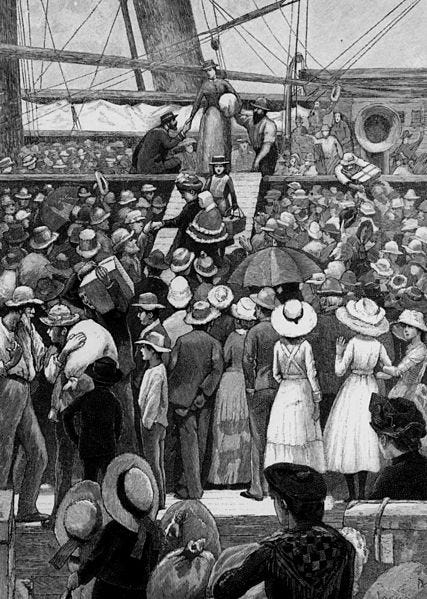

In September 1885 a young Jewish woman named Rosa Frankenstein boarded a ship that would take her on the long and perilous journey from her London home to Sydney, Australia, where she was to be married to her fiancé.

Rosa would have been in a tumult of excitement and anxiety as she embarked on the month-long voyage to the other side of the world.

Not only was she leaving behind her family and friends but also the familiar haunts of hustling, bustling, smog-choked London. It was her home. She had lived there all her life.

Rosa knew little about Sydney and not much about Australia.

She knew even less about the man to whom she would be married.

Her fiancé, who went by the glamorous names of Jules Francois, was a passionate campaigning reporter for the Sydney-based newspaper, The Bulletin.

During his time on assignment in London, which had begun in 1883, he had assiduously exposed the miseries of the poor, the avarice of the rich, the corruption of governments, and the hypocrisies of religions.

His readers in Sydney and beyond lapped up his dispatches depicting the cruelties and absurdities of the English ruling classes.

Jules had told Rosa that he had been born in France and that his mother was French – and a Jew.

Rosa and Jules met some time in 1884, and on March 4 1885 he returned to his Sydney home to be editor of The Bulletin – and to make preparations for their nuptials.

Jules embarked on the SS Lusitania. One of his fellow passengers was the artist Tom Roberts who immortalised their voyage in his magnificent Coming South, today on display in the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Roberts recorded that Jules was a great conversationalist, but it seems he made no mention of his upcoming marriage to Rosa Frankenstein, who arrived in Sydney several weeks later.

But there was to be no happy-ever-after for Rosa: only shattered dreams, a broken heart, loneliness and alcohol.

For Jules Francois wasn’t the man he had made himself out to be.

Otherwise known as

Jules Francois was in fact John Feltham Archibald, a journalist of some renown and considerable ability.

He was the founding editor of the radically republican weekly The Bulletin, and successful promoter of Australian literary giants such as the poets Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson.

He was an excellent journalist and a first-class copy editor.

Today his name lives on in the eponymous Archibald Prize (awarded annually for Australia’s best portraiture) and the Archibald Memorial Fountain in Sydney’s Hyde Park.

Despite what he told Rosa, Archibald was not born in France, but in Kildare near Geelong, Victoria, in 1856.

His father Joseph was a policeman from Ireland. His mother, Charlotte Jane nee Madden, was neither French nor a Jew. She was a Catholic.

Charlotte died four years after his birth leaving Archibald to be cared for by his aunt and grandmother.

He was educated at the local Roman Catholic and National schools, and later at Warrnambool Grammar School - leaving at the age of 14 to be an apprentice compositor at the Warrnambool Examiner.

He burned to be a journalist so he moved to Melbourne a few years later in search of new opportunities.

It was here he became besotted with France and the French. He lived for some time in Emerald Hill at a boarding house operated by a Breton couple who apparently impressed and influenced him.

He was also enamoured by French philosophers of the Enlightenment, particularly François-Marie Arouet – better known as Voltaire – and he may have adopted the pose of a flaneur in homage to the likes of the poet Charles Baudelaire and novelist Gustave Flaubert.

After bouncing around between jobs for several years, Archibald in 1880 established The Bulletin in Sydney with William Henry Traill. Circulation reached 80,000 in the late 1880s, a considerable achievement at a time when the New South Wales population had just touched one million.

Archibald had headed to London in 1883 after a financially ruinous libel case (which saw him jailed for a few days) and not long after arriving discovered his bank had failed. He was not happy.

A Presbyterian Church wedding

Archibald and Rosa were married in a Sydney Presbyterian church on November 22 1885.

The marriage certificate (registration number 1895/1885) gave his birthplace as France.

Rosa gave birth to a child who died while still a baby. Rosa sought solace in alcohol and it appears that thereafter she and Archibald had little to do with one another. She died in 1911.

Archibald’s biographer, Sylvia Lawson, pays little attention to Rosa. She notes that Rosa possessed “sweetness and charm, but few inner resources” and that her life, which ended in 1911, “went to waste”.

Lawson says Archibald “worried and grieved over her continually. He spent thousands on their house in Darling Point, but none of these clothes, presents, jewels and flowers he lavished on her could rescue her, or make more real a marriage in which he neither gave nor received companionship. In a sense, from 1886, Archibald had no personal life”.

It was, says Lawson, a “most unfortunate marriage”.

As he aged, Archibald suffered from anxiety, depression and mania. And as he grew older he became physically frail and restless. He described his life as all “nerves and self-consciousness and misery, bromide of potassium, chloral, ether, opium, and all the hypnotic derivations of the aniline dyes”.

It is telling that a retrospective tribute to Archibald, published in the Sydney Sunday Herald in November 1942, ended by asserting that he had “lived a bachelor” and that Sydney “was his one love”.[i]

Following a nervous breakdown, Archibald was committed to Sydney’s Callan Park Asylum in 1906, Rosa co-signing the committal papers.

Archibald recovered from his psychiatric condition, was released from Callan Park, and went on to work again in journalism. He died in 1919.

Who was Rosa Frankenstein?

The Frankenstein family name – described by Sylvia Lawson as “unlikely” - is German-Jewish Ashkenazi, and in the 19th century was common in areas such as Silesia and the Palatinate.

It is not possible to be certain, but records indicate that a couple who may have been Rosa’s parents – perhaps named David and Amelia - may have been born in Breslau (today Wroclaw) in Silesia.

At some point they migrated to London but by 1881 David was a widower. Archibald described Mr Frankenstein as “a Jewish merchant, dealing in coffee”.

At the very least Rosa would have had some basic education, including religious education. She may have attended one of London’s Jewish day schools, which provided girls with classes in subjects such as Geology, Biology, Chemistry, Geometry, Arithmetic, Geography, and History.

A thoroughly first class talker

We don't know how Rosa and Archibald met, although there is a story that in London in 1884 Rosa nursed Archibald through an illness after which, it seems, Archibald proposed, Rosa accepted and they became engaged.

Whatever, why did Rosa decide to accept Archibald’s marriage proposal?

The Occam’s Razor answer might be – they were two young people who were attracted to one another, they fell in love, and hatched a totally romantic plan to go together to Australia where they would be married and live a life full of joy and happiness.

Jules was intelligent, bright, sensitive and, if not a good listener, a thoroughly first class talker.

Rosa was equally bright – one account has it that she spoke “five or six European languages” and enjoyed reading.[ii]

Further, Rosa’s father may have encouraged her to take this opportunity for economic security and prosperity with the kind of man you don’t find in London’s East End. Jules was a journalist, an editor – they don’t grow on trees.

But there is another possibility.

It is possible Archibald had convinced himself that the Jules Francois French-Jewish heritage persona was actually real. If so, it is likely Rosa and her family would simply accept his story – including the “fact” that his mother was Jewish.

And that could only mean one thing: that Archibald was a Jew. Under Halakhah (Jewish law) Judaism is matrilineal, therefore Jules Francois must be Jewish too.

Rosa and her family would think she was being wooed by a fellow Jew.

It would be a very surprised Rosa, then, who found herself getting married to a goy in that Sydney Presbyterian church in November 1885.

There was nothing she could do. She couldn’t go home, she couldn’t run away. She had no family or close friends who could help her out.

For better or worse, she was stuck with the man calling himself Jules Francois.

Thousands of miles from home

The marriage deteriorated over time. What appears to have developed between Archibald and Rosa was a personal, private misery – especially difficult in the 19th century when one could not simply walk away from a marriage.

For a woman, divorce was expensive and difficult to obtain. And where would she go? She was thousands of miles from home with no money of her own. She took to drink.

Archibald found refuge in daily life at the Bulletin, becoming a 14-hours-a-day workaholic ridden with a growing cluster of psychological problems.

Sylvia Lawson notes that Archibald “worried and grieved over her continually … In a sense, from 1886, Archibald had no personal life”.[iii]

It is perhaps telling that a retrospective tribute to Archibald, published in the Sunday Herald in November 1942, ended by asserting that he had “lived a bachelor” and that Sydney “was his one love”.

In his memoirs written in 1907 Archibald made no mention of a mysterious French-Jewish heritage. His father was Joseph Archibald, then aged 90 and still living. His mother had died when he was five years old.

At the end, Archibald exited the world the way he came in – as a Catholic. He is buried in the Catholic section of Waverley Cemetery, Sydney.

[i] Claude McKay, ‘J F Archibald was a living legend’, The Sunday Herald, Sunday 23 November 1942

[ii] ‘The Sydney Bulletin. Its Clever Editor. A Character Sketch’, Warnambool and District Newspaper Cuttings, February 1, 1894 p68-69, Mitchell Library, Sydney

[iii] Sylvia Lawson, 'Archibald, Jules François (1856–1919)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/archibald-jules-francois-2896/text4155, published in hardcopy 1969, accessed online 12 May 2014. This article was first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 3, (MUP), 1969