They did WHAT!? A new series on historic decisions and the reasoning behind them

No1 - Tostig Godwinson and the death of the last Saxon king

By DAVID MYTON

A new era began in England on October 14 1066 when the army of William, Duke of Normandy, defeated that of reigning Saxon king Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings.

Harold, and most every other Saxon who counted, including his brothers Leofwine and Gyrth, were killed in the battle. And so William took the prize he had long coveted - the throne of England. He was crowned King at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066.

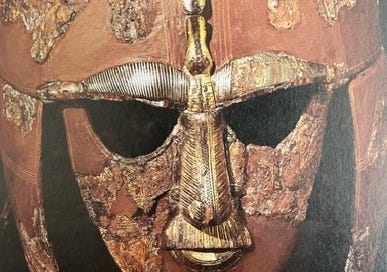

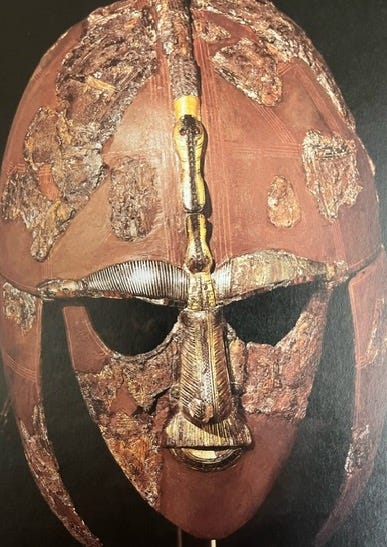

Harold’s army at Hastings was no push-over – it included a mass of amateur fyrd militia but was leavened by the special forces of the day, fearsome axe-wielding professional warriors known as Housecarls.

And they might well have triumphed over the Normans had it not been for the malice and treachery of Harold’s bad boy brother, Tostig.

Tostig and a host of Vikings led by the ruthless Norse Harald Hardrada invaded the north of England in September 1066.

And so Harold had to leave his southern defence posts and march north with his army to deal with this unforeseen menace – a 200km journey described as “one of the signal feats of military history”.

Harold and his army defeated the Viking host at the Battle of Stamford Bridge just a few miles from York on September 25, 1066. Both Tostig and Hardrada were killed in the clash.

Then Harold heard the news that William had landed at Pevensey on the south coast – so he and his army turned around and repeated the marathon march to do battle with the man who wanted his throne.

It didn’t end well for Harold – he was killed – and the Saxon people suffered for years under William’s ruthless reign.

Why did Tostig decide to betray his brother and King?

In trying to understand Tostig’s actions and behaviour, we need to look at the historical and domestic situation in which he existed - especially the role of his

cunning and ruthless Father.

At first glance Tostig’s actions seem to be the work of a dangerous and deranged villain motivated by resentment and greed.

In one view he was guilty of breaching contemporary social norms by ignoring or rejecting the heroic codes we see reflected in old English and Anglo-Saxon literature with their meditations on courage, bravery, skill at arms, renown, and loyalty – especially commitment to clan and their leader.

Says Beowulf …

In the time I was given I lived in my own land

ruling my people well

never turning to treachery

or swearing to oaths

contrary to right

… and The Wanderer

A wise man must be patient

He must never be too impulsive …

Nor too reckless

… and The Seafarer

Check a violent mind

Control it with firmness

Be trustworthy to others …

We can see these Anglo-Saxon codes re-enacted, if you like, in modern literature and film - think for example of the depiction of the fictional Riders of Rohan in JRR Tolkien's The Lord Of The Rings.

Tolkien, among other things, was a professor of Anglo-Saxon and he knew what he was talking about when it came to the Saxons and their codes of behaviour.

The Rohirrim are basically Saxons on horseback, although the real Saxons didn't fight mounted. They are the good guys. Aragon calls them a stern people/loyal to their lord/wise but unlearned.

It's hard to imagine a Tostig-type character among them, but just as many modern people will not have read The Lord of the Rings or seen Peter Jackson's trilogy of movies, so back in the Saxon day it's by no means certain everyone would have been familiar with Beowulf and the like.

And, even if they were, they might have thought it was good entertainment but implausible tosh contrary to their lived experience. We don't know.

In trying to understand Tostig's actions and behaviour we need to look at the historical and domestic situation in which he existed and developed, and then try to determine how aberrant or not he was.

A cunning, clever and ruthless Father

So who was Tostig? He was born sometime between 1023-1028 at a time when battles, fights and vendettas over land and clan and personal aggrandisement were the rule, not the exception.

Tostig's father was the cunning, clever and ruthless Godwin son of Wolfnoth. His mother Gita was the daughter of a warlike Danish chieftain.

Godwin senior hustled his way to the top to be England's go-to hitman and bagman. He was an advisor to the ruthless King Knut, the man who created the English earldoms in the first place.

And after Knut’s death he served Kings Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut, and the rather more saintly Edward the Confessor, who nevertheless knew all about power.

Now Godwin's royal connections were also enhanced when his daughter Edith became Queen of England after marrying King Edward in 1045 - and so Godwin senior hustled ever closer to the throne as the new king's father-in-law.

Godwin's other sons included the earls Svein, Gyrth, Leofwine, Wulfnoth, and of course the famed Harold - crowned King of England in 1066 following the death of king Edward.

In the words of the historian N J Higham, Godwin senior's favourite pastime was amassing land, wealth and influence - often at the expense of others including churches and the king himself.

The historian Hugh Bibbs says Godwin senior never acted out of patriotic service, only self-interest. He benefited from natural leadership ability founded on an impressive personality and physical courage, rather than on loyalty to others, he writes.

Tostig's father was his role model. He watched his dad at work and saw that power, ruthlessness, cunning and violence were the exact traits you needed to make it big in this world - and to a large extent that was true.

Then old man Godwin died at Winchester in 1053 and was buried in the Minster there close to the graves of his old bloodthirsty patrons Knut and Harthaknut.

Now Tostig's big brother Svein was a fraternal role model, offering lessons to Tostig in kidnap and murder. In 1046 Svein, for reasons best known to himself, abducted the Abbess of Leominster in Herefordshire - a crime for which he was sent into exile.

On return, Svein murdered his cousin Beorn who refused to give back lands he was granted in Svein's absence.

The family that slays together stays together

In 1051 the entire Godwin clan was sent into exile after Godwin senior refused King

Edward's order to attack and punish the people of Dover over a dispute with King Edward's brother-in-law Eustace, the Count of Boulogne.

This prompted the observation by one historian that the Godwins upheld the adage that “the family that slays together stays together”.

Tostig at times did show loyalty to the family cause, specifically to big brother Harold. He displayed real bravery and astute tactical and command skills in 1062-63 when he helped Harold in a successful campaign in Wales against the forces of King Gruffyd.

By this time the Godwins held lands, goods and property of enormous value, perhaps even greater than that of King Edward himself.

As authors Robert Lacey and Danny Danziger say, in the Anglo-Saxon period “the greatest lords were the greatest thugs. For the English aristocracy, like the military elite of every European country, was a cadre that had been trained to kill. To be noble was to wear a sword and to throw your weight around”.

It was by throwing his weight around in the wrong place and with the wrong people that landed Tostig in all kinds of strife - and which set him on the course to his ultimate betrayal.

In 1055 at the age of around 32, Tostig was appointed the Earl of Northumbria. It was a big gig and it wouldn't be easy.

This wasn't the Northumbria of today, a relatively small council area between the rivers Tees and Tweed in northeast England. Tostig’s Northumbria included huge tracks of land north of the River Humber, taking in today's Yorkshire, County Durham, modern Northumbria, and lands to the west and up to the Scottish border.

It was a long way from England's engine room of London and the South; transport and communications were poor. It was culturally diverse with a mix of Anglo-Saxon peoples and Scandinavians - the Vikings - who had been raiding and settling for well over 100 years.

Its people were relatively independent and historically they had paid little, if any, taxes. Its capital York - whose modern name derives from the Danish Jorvic - had deep Viking roots (and still does) only really integrating into the Saxon kingdom from about 954CE.

These northerners were a tough and stubborn bunch who didn't like to be pushed around. At first, Tostig seemed to take the earldom in his stride, even finding the time to take the then-fashionable pilgrimage to Rome.

There was some border incursion trouble in the Cumbria region from his erstwhile Scottish ally, king Malcolm, but Tostig took no action (incidentally he also was acquainted with Macbeth, the Macbeth from Shakespeare).

‘Harsh, obstinate and impatient of opposition’

Then things started to go wrong. Tostig was often an absent landlord, frequently finding reasons to head south for a break whenever he could. And when he was in Northumbria he played the tough guy, raising taxes, introducing harsh laws, stealing land, and interfering with local customs.

Two thegns who called on him in York to protest were killed by some of Tostig’s henchmen, and more violence followed.

As historian Edward Augustus Freeman puts it, it is clear that his government had by this time “degenerated into an insupportable tyranny”. This, says Freeman, is “not uncommonly the case with men of his disposition: harsh, obstinate and impatient of opposition”.

By now, the people had enough and rose in revolt. They raided Tostig's treasury and armoury in York, making off with his weapons and his cash.

They wanted Tostig removed as earl … or else. They united under two young Mercian nobles Morkere and Edwin (who pop up again on September 20, 1066 at the Battle of Fulford as the leaders the Saxon forces) and marched south torching towns and pastures along the way.

Tostig fled and big brother Harold was left to sort out the mess. The rebels demanded that Tostig be removed and banished.

Harold was in charge of negotiations and it was tricky: if he rejected their demands an unpredictable and bloody civil war appeared likely.

He saw no alternative but to give into the demands of the rebels, so they got a new earl, Morkere, and a restoration of the old laws that existed prior to Tostig's rule.

On November 1, 1065, Tostig, his family, and some loyal thegns, sulking and depressed, sailed to exile in Flanders to the court of his father-in-law, Count Baldwin.

Here Tostig would brood and plot vengeance on brother Harold.

Just a few weeks later King Edward died and brother Harold was crowned king on January 6, 1066. And Tostig set about launching his reprisals. What would his father have done, how would old man Godwin have responded?

Well, he would strike back and reclaim what was his, and woe betide anyone who got in his way.

And that's what Tostig attempted to do, albeit somewhat haphazardly launching raids on the Isle of Wight, England's south and east coast, and forging an alliance with the Norwegian Viking Harald Hardrada, a fateful pairing that would lead to both of their deaths at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066 at the hands of King Harold’s army.

You had to fight for the right to rule

I think that in Tostig’s actions - the raiding, plotting and scheming, and the desire to be restored to rank and fortune – he was merely enacting what he had learned from his father and his golden boy brother Harold, and the rest of the Godwin clan: you had to fight for the right to rule.

But Tostig acted more from outrage, anger and damaged pride rather than from cool, rational self-interest and calculated compromise.

Tostig's disappointment went deep because he had expected brother Harold to support him in the Northumbrian fracas right or wrong. And he could not understand any cause for Harold's hesitating so to do except taking the side his enemies, writes the historian Edward Freeman.

Tostig did what he did because he was a man of his times and his upbringing. But he let his emotions, rather than rational self-interest, dominate his decision-making - something his father would never have done.

Tostig of course didn't and couldn't know that his actions at Stamford Bridge along with Hardrada would result in brother Harold's defeat of the Battle of Hastings a few weeks later.

Perhaps if he'd live to see it happen he would have been happy and looked for an opportunity in William’s court - and that's probably what his father would have done.

But he wouldn't have messed it up as surely as Tostig would have done.

References

Hugh Bibbs, The Rise of Godwin, Earl of Wessex - http://www.medievalhistory.net/page00...

Winston S Churchill, A History Of The English-Speaking Peoples (One Volume Abridgement by Christopher Lee) Cassell, London, 1999.

Edward Augustus Freeman, The history of the Norman conquest of England, its causes and its results, Clarendon, London, 1868 .

Tostig Godwinson - https://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/sax...

N J Higham, The Death Of Anglo-Saxon England, Sutton Publishing, 2000.

David Howarth, 1066 The Year of the Conquest, Book Club Associates, London, 1978. Robert Lacey & Danny Danziger, The Year 1000 – What life was like at the turn of the first millennium, Abacus, 2000.

Marc Morris, The Norman Conquest, Hutchinson, London, 2012.

Anne Savage (Translator and Collator), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. The authentic voices of England from the time of Julius Caesar to the coronation of Henry II, Guild Publishing, London, 1982.

T.A. Shippey, JRR Tolkien. Author Of The Century, HarperCollins, London, 2000. Dorothy Whitelock, The Beginnings of English Society, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1972.

Martyn and Hannah Whittock, 1016 & 1066. Why The Vikings Caused The Norman Conquest, Robert Hale, Wiltshire, 2016.

David Wilson, The Anglo-Saxons, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1966.

It’s nice to see history treated as if real people were involved. Bravo sir, bravo.

Thank you for this interesting essay! I studied Old English when I was studying English in grad school, but I know more about the literature and the language than I know about the history. You have expanded my knowledge of this interesting period.