They did WHAT!? When Winston Churchill ordered the destruction of France’s navy

It was 'the most hateful, the most unnatural and painful' decision of his career

By DAVID MYTON

On July 3 1940, at the command of Britain's wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Royal Navy warships attacked the French fleet anchored at Mers-el-Kebir near Oran in French Algeria.

Some 1297 French servicemen were killed and many others injured in the Royal Navy's assault, which sank the battleship Bretagne and damaged five other vessels.

Churchill later wrote that the decision to attack the fleet of Britain’s erstwhile ally was “the most hateful, the most unnatural and painful in which I have ever been concerned”.

He didn't say it was wrong.

In order to make sense of historical decisions we need to consider the context in which choices and actions were made and framed.

As authors Sonke Neitzel and Harald Welzer write, humans interpret what they perceive and on the basis of interpretation draw conclusions, make up their minds, and decide what to do.

Human beings, they say, never act on the basis of objective conditions, nor do they act solely with an eye towards cost-benefit calculations, adding “whatever human beings do, they could always have done differently”.

On the brink of catastrophe

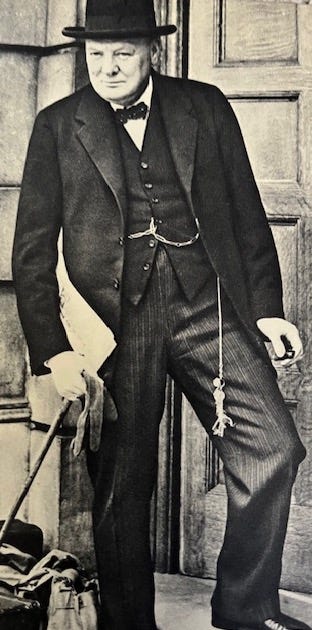

Winston Churchill was appointed Britain's Prime Minister, Minister of Defence and leader of the House of Commons on May 10 1940, having previously served - beginning on September 3 1939 - in the War Cabinet, the Military Coordination Committee, the Supreme War Council, and as First Lord of the Admiralty.

Churchill was an experienced political operator going back to World War One. And he needed to be: on that day, May 10, Britain was deep in crisis and on the brink of catastrophe.

Allied forces were in disarray after the German Wehrmacht attack through Holland and Belgium into France.

The British Expeditionary Force and the French Army were out fought and out thought by the Germans, and were either cut off or forced back to the coast.

Also at this time British forces were up against it fighting the Germans in Norway in a campaign largely instigated by a Churchill and described by the military historian Basil Liddell Hart as “slow, hesitant and bungled”.

So Churchill decided to end the Norway campaign and on June 7 1940 the allied forces were evacuated from Narvik.

As the situation deteriorated in France, Churchill and his Cabinet had to consider several French requests for increased Royal Air Force fighter support, which they rejected being “not yet convinced that we could afford to divert more resources from this country”.

Concern was growing that Britain itself would soon be attacked so more effort would be needed to shore up homeland defences, including keeping fighter aircraft at readiness.

On the morning of May 15 France's Prime Minister Paul Reynaud called to tell Churchill that the Germans had broken through at Sedan. The road to Paris was now open and the battle was lost, he said.

By May 20 Churchill thought it likely that considerable numbers of Allied troops would either be cut off in France or driven in to the sea.

Churchill told War Cabinet that as a precaution the Admiralty should assemble a large number of small vessels in readiness to proceed to ports and inlets on the French coast.

‘Wars are not won by evacuations’

The mass of British troops and their allies were now in full retreat to the coast and falling back on Dunkirk, and between May 26 and June 4 Operation Dynamo saw the evacuation from the beaches and the harbour at Dunkirk of more than 330,000 British and Allied troops.

On June 4 Churchill told Parliament “we must be careful not to assign to this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations”.

Between May 16 and June 13, Churchill flew five times to France and back for increasingly despondent meetings with the French leadership. Churchill expended much energy on these meetings as he was attempting to cajole the French into prolonged resistance, declaring that “the British people will fight on until the new world reconquers the old”.

At the final meeting in France, Churchill told Admiral Francois Darlan “you must never let them get the French fleet”, and Darlan “promised solemnly” he would never do so.

During the French campaign Britain lost 7,000 tons of ammunition, 90,000 rifles, 2,300 field guns and artillery, 82,000 vehicles, 8,000 Bren guns and 400 anti-tank guns – all hard to replace.

Churchill now brought his focus back to Britain, declaring that “everything must be concentrated on the defence of our island”.

On June 10 Paris was declared an open city and on June 16 the French asked for an armistice with Germany. This was signed on June 22 and came into effect on June 25. Philippe Petain was appointed chief of state of Vichy France.

Britain was alone. The pressure was intense. There was a shortage of armaments, Luftwaffe air raids were increasing, and the Battle of Britain was about to begin. There was genuine concern that Hitler had plans to invade.

So now the fate of the French fleet became an overriding concern. Churchill wrote to Petain and Marshall Maxime Weygand, insisting that they should “not injure their ally by delivering over to the enemy the fine French fleet”. Such an act, he wrote, would scarify their names for a thousand years of history.

Churchill added that the possible addition of the French navy to the German and Italian fleets “confronted Great Britain with mortal dangers”.

Article 8 of the armistice prescribed that the French fleet “shall be collected in ports to be specified and there disarmed under German and Italian control”. It was therefore clear, said Churchill, that French war vessels could or would pass into that control while still fully armed.

Who in his senses would trust the word of Hitler?

It was true that the German government said they had no intention of using the fleet for their own purposes, Churchill wrote, but added “who in his senses would trust the word of Hitler after his shameful record and the facts of the hour”.

“At all costs, at all risks, in one way or another we must make sure that the navy of France did not fall into the wrong hands and there perhaps bring us and others to ruin,” he said. It must be neutralised or destroyed. “The life of the state and the salvation of our cause were at stake,” he wrote.

“No act was ever more necessary for the life of Britain and for all that depended on it.”

Churchill was fully supported by the Ministers of the War Cabinet, who had resolved that “all necessary measures” should be taken.

Operation Catapult, which comprised the simultaneous seizure, control or effective disablement of all the accessible French fleet, began on July 3 when in a surprise action all the French vessels at Portsmouth and Plymouth were taken under British control.

Meanwhile, Force H commanded by Vice Admiral Somerville, and including the battlecruiser HMS Hood, battleships Valiant and Resolution, the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, and 13 other warships, sailed from Gibraltar to Mers-el-Kebir and Oran.

The French fleet command was to be offered several choices designed to neutralise their ships, including joining the British, sailing with reduced crews to British ports or to the US, and failing that, the French could scuttle their own ships.

Admiral Somerville told the French: “I have the orders of His Majesty's Government to use whatever force may be necessary to prevent your ships from falling into German or Italian hands.”

None of these options was taken up. The fleet was subsequently attacked.

Afterwards, Churchill addressed Parliament, explaining the action and setting it in the context of what he said “may be the eve of an attempted invasion or battle for our native land”.

Members of Parliament “almost to a man” gave him a standing ovation.

Churchill said he was sure that the elimination of the French navy by violent action “produced a profound impression in every country … It was made plain that the British war cabinet feared nothing and would stop at nothing” not just about neutralising the fleet but also sending a message to friend and foe”.

‘Fear proved to be a bad counsellor’

Was Churchill justified in ordering the destruction of the French fleet?

The British military historian Basil Liddell Hart thought not. “Fear proved in the long term to be a bad counsellor,” he wrote.

Admiral Somerville declared that it was the “biggest political blunder of modern times and would rouse the whole world against us … we all feel thoroughly ashamed”.

According to the historian Richard Lamb, the order to sink the French fleet was Churchill's “greatest blunder” and indirectly led to thousands of British casualties in the subsequent Syrian campaign.

Did Churchill make the right decision? Well, we don't know what would have happened had he not ordered its destruction. The Nazis could have used it, for example, to interdict shipping in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, perhaps even in the Indian Ocean.

It could also have been used as seaborne artillery to support an invasion of Britain in Operation Sea Lion, for example.

Could the British afford at that time, in that place, in that context, to take the risk of not neutralising it?

Churchill and the War Cabinet judged that they could not take that risk.

REFERENCES

‘Attack on Mers-el-Kébir’ https://military.wikia.org/wiki/Attac...

Winston S Churchill, The Second World War Volume 2, Their Finest Hour, Reprint Society, London 1951

Martin Gilbert, Finest Hour. Winston S Churchill 1939-1941, Heinemann Minerva, London 1983

Sir Basil Liddell Hart, History Of The Second World War, Book Club Associates, London, 1970

Boris Johnson, The Churchill Factor. How One Man Made History, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 2014

Richard Lamb, Churchill As War Leader, Carroll & Graf, Bloomsbury, 1993

Sonke Neitzel and Harald Welzer, On Fighting, Killing and Dying. Soldaten. The secret WW11 transcripts of German PoWs. Random House, 2012