True confessions of a journalist in 1970s Northern England

I saw it with my very own eyes ... fires, accidents, drownings, plus the occasional ghost, a bell ringer, and a dead man in a coffin

“Journalism is not a profession or a trade. It is a cheap catch-all for fuckoffs and misfits — a false doorway to the backside of life, a filthy piss-ridden little hole nailed off by the building inspector, but just deep enough for a wino to curl up from the sidewalk and masturbate like a chimp in a zoo-cage.” – Hunter S. Thompson

By DAVID MYTON

Journalism and journalists often get a bad rap these days. It was ever thus really, except that the heat gets turned up to maximum and for longer now thanks to social media and the power of the internet.

Recently, for example, a well-known YouTube site describe newspapers as “worthless rags” and journalists as “dirty, dirty smear merchants”.

Here is a true confession: I’ve been a journalist for more than 50 years. I’ve worked on newspapers in the UK and Australia, from reporter to an editor-in-chief. I’ve also been a college lecturer in journalism and served some time in PR.

This is a personal history of my days as a young reporter in 1970s north of England, including aspects of training, work experience, and what it was like working as a journalist in that time.

Back in the 1970s there was no Internet, no online journalism, no fake news, no woke, no Twitter, no YouTube, no Instagram, no Facebook.

If as a reader you wanted to complain about something, you wrote a letter to the editor, or demanded an apology, or sued for defamation, or all of the above.

In the early 70s “the truth” seemed obviously binary: something was either right or wrong, factual or false; it either existed in reality or it didn’t, and words held their traditional dictionary definitions.

It was your job as a reporter to be accurate, factual and fair. Words held their traditional dictionary definitions. Cultural sensitivities were much less intense. But there were rules, and if you broke them you would be punished.

Your job as a reporter was to provide the reader with the facts - not to make judgments and express your own opinion.

Practical journalism

In my time I have been a news reporter, sports reporter, feature writer, opinion writer, a sub editor, a chief sub editor, a section editor, a newspaper editor, and Editor in Chief of a media group. I’ve also lectured in journalism at a private college, and worked on the “other side”: in public relations.

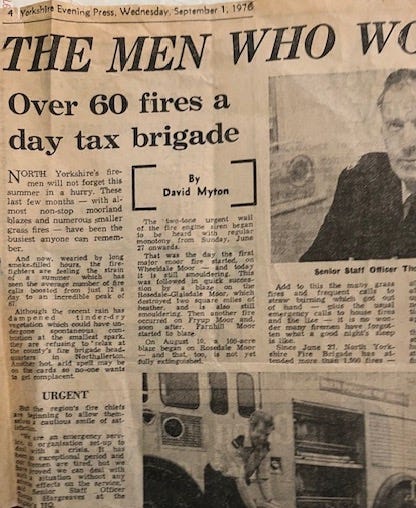

I began my studies in journalism in September 1972 at Richmond College, Sheffield, on a one-year course in practical journalism authorised by the English National Council for the Training of Journalists.

You needed this qualification to get a job as a trainee reporter (there were other ways in for University graduates). Once employed, you were apprenticed to a newspaper for up to three years. The paper had a duty to train you in all aspects of Journalism.

Cadets had a duty to apply themselves, to learn and to progress to increasingly difficult jobs. At the end of this time you had to sit a day-long exam - which if you passed meant you were a trained, qualified journalist with a pretty substantial pay increase.

Whatever impressions you may have of journalists and journalism, it is not an easy job. It can be very complicated and stressful; and immutable deadlines are a fact of life – as is complicated subject matter.

If you libel someone you can be sued - and these days, of course, you can be shamed and traduced on social media if you upset the wrong people.

I grew up in a working-class family on a council housing estate - social housing - in the north of England. My mother was a cleaner, my dad worked variously in shops and factories. We never had much money.

I left school at the age of 16. I did some office work, and also worked in a factory packing chocolates. After a time I enrolled at a technical college and gained some advanced qualifications in English language, literature and law.

I recall attending a careers fair at college and seeing a pamphlet spruiking jobs in journalism. On the cover was a casually dressed young man writing in a notebook as he watched the fire brigade trying to stop a house from burning down. And I thought … I could do that!

I applied to undertake a one-year pre-entry course in Journalism at Richmond College, Sheffield – the basic qualification you needed to work as a journalist in the UK – and began my studies in September 1972 with a bunch of other students from mostly middle-class backgrounds.

It was an entirely practical course – run by former journalists - that taught shorthand and typing, news-gathering, reporting, feature writing, media law, politics, and sociology. We didn’t discuss any academic media theory.

We were frequently sent out on assignments, such as being dropped off in villages in nearby Derbyshire and told to find a good, publishable story within four hours. And mostly we did.

We also had experiential visits to coal mines, steel works, and emergency services - fire-brigade, ambulance, police – an eye-opening experience from the sharp-end of life.

There were lectures on national and local government, law – especially defamation - and the reporting of court cases, tribunals, and the like.

Rudyard Kipling’s “six honest serving men” - who, what, where, when, why and how – was the gold standard. Always double -check names, ages, addresses, times and dates.

Most of us would work for papers in towns and cities where the publication would be the major source of local news and advertising - get a name wrong, you could lose a reader; libel someone important, you could lose their business.

‘If it’s a sin put it in …’

It was okay to add some spice and drama to your story if applicable – “if it’s sin put it in” was the watchword, especially with scandalous court cases where accurate reporting was protected by law.

I graduated from the course in June 1973. I soon found work as a junior reporter on the bi-weekly Gainsborough News, based in a small town amidst vast farmlands straddling the River Trent in Lincolnshire.

It was a great thrill - I was a proper cub reporter. The first thing I had to get my head around was agricultural shows - to report on the sale of cows, bulls, pigs, sheep, and goats.

I didn't know what I was doing, but the show managers and farmers explained to me what needed reporting on, and why. The farmers were gruff, but also patient and kind when explaining to you the distinguishing features of a Lincoln Longwool sheep or a Lincoln Red Cow. This stuff was important to them. You had to get it right.

Another round I had was called Club Call. This involved a weekly visit to Gainsborough’s several Working Men’s Clubs, as they were called in those days: essentially it’s a social club where you could drink, eat and play games such as darts and dominoes. Despite the name, back in the 70s women were present in those clubs.

My job was to find stories of achievement - life passages, anniversaries, birthdays, retirements and so on. Inevitably those I interviewed insisted on buying me a drink, usually a pint of bitter. By the end of the night I was often totally tanked, and thus followed a very wobbly and blurry bicycle ride back to the office.

I was also introduced to sports reporting, specifically football matches played by the local team, Gainsborough Trinity, in the Northern Premier League - the seventh level of English football.

I really enjoyed this. It was a great experience traveling on the team bus with the players to games at various Northern England towns. Regardless of the level, people take their sport seriously. So again, the journalist has to learn the skills necessary to describe the action on the field, and identify why the winners won and the losers lost. You had to be constantly alert and focused.

When I had dreamed of a career in journalism, I had imagined myself as an Orwell or Steinbeck character perhaps covering some tragic Civil War somewhere - I had no idea.

I thought writing would be easy - but this wasn't make-it-up creative writing. It was about getting the facts and recording them clearly and concisely. That’s not as easy as it sounds.

Births, deaths and marriages

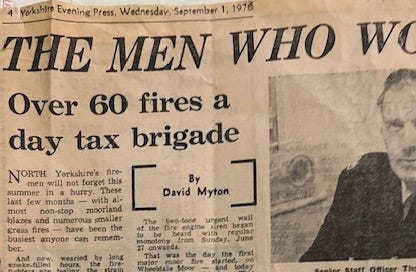

After a few months I moved to a new job on the Yorkshire Evening Press, a multi-edition, six-days-a-week newspaper in York with 64,000 daily sales in a city of about 110,000 people. It made a lot of money from display advertising and classifieds, including births, deaths and marriages.

In my first few weeks I was tasked with writing obituaries of well-known locals who had recently died. This is not as easy as it sounds: you have to dig around in the files for info and interview surviving relatives and friends with empathy. It was good training in research and accuracy.

I was also introduced to “the rounds” – daily checking in with the police, fire brigade, and ambulance services for news on overnight crimes, accidents, and fires.

This is bread and butter for local newspapers – generally it’s where the most “dramatic” stories come from: the murders, muggings, accidents, drunken brawls and drownings (A surprisingly regular occurrence in York then, the victims mostly young men thinking it was a good idea to swim across the cold and deep River Ouse after a night on the booze. It was never a good idea.)

On one occasion I was tasked with writing the obituary of an important city dignitary who had recently died. As part of this I went to interview his widow. On arrival at her house, an elderly lady invited me in, made me a cup of tea, and readily answered my questions about the achievements of her late husband.

The she asked – “would you like to see him, love?”

Thinking that she meant a photograph, I said yes, at which she beckoned me to follow her into an adjoining room. And there was her late husband, resplendent in a smart dark suit at rest in an open coffin. Although this was then a relatively common practice I was a little taken aback. She asked me: “What do you think, love?”

I said: “He looks lovely”. To which she replied, “Aye love, he does, he was a grand man.” With that we went back into the other room to resume the interview.

I covered numerous city council meetings dealing with things like development applications, car parking changes, retail shopping regulations, new roads and bus lanes, industry plans, rate increases - all the things that keep a community ticking over.

On Saturday February 15, 1975, I scored my first page one lead - a house fire in which “an expectant mother dashed twice into a blazing room to rescue two young children” while “a man in an upstairs room leaped 15 feet to safety from a bedroom window”.

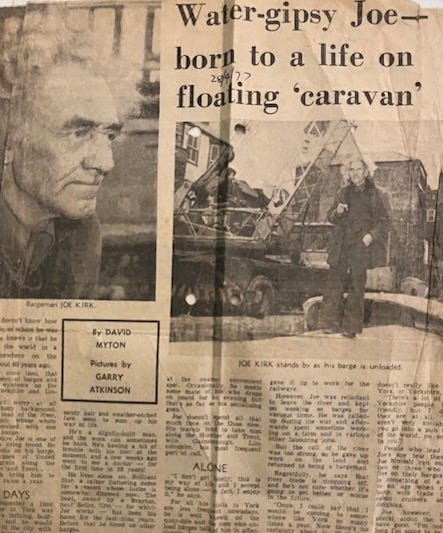

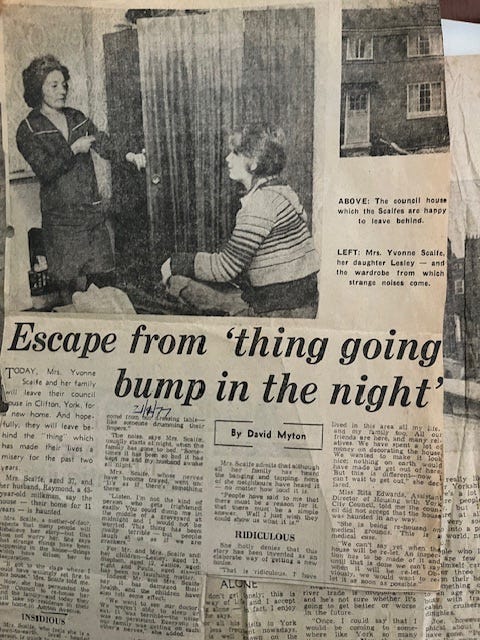

I wrote features about a haunted house, the art of watching cricket on television, film and theatre reviews, and a profile of a “water gypsy” - a man who had lived on a barge for much of his life, ferrying cargos from the docks in Hull to York on the River Ouse. I also interviewed an old man who was retiring from his job as a bell ringer at an old city church – the last person to do that job.

In June 1975 I passed the National Council for the Training of Journalists proficiency test in practical journalism - at the age of 21 I was now a qualified journalist. It was the end of the beginning and the start of a 50-year career.

Gonzo! Fear and Loathing in journalism. Beginning with a self-deprecating quotation from Raoul Duke, Doctor of Gonzo Journalism is good Gonzo. Warren Hinckle, of Ramparts fame, tells us how Gonzo came to be: “Gonzo journalism – the unedifying concept of the reporter as the proactive part of the story, with equal emphasis on the imaginative and comic as the fact – grew out of the 1970 assignment I gave Thompson for Scanlan’s Monthly. Gonzo started when Hunter called me from Colorado at home in San Francisco about 4 a.m. – a normal social hour – to say that he wanted to cover the Kentucky Derby which was then but two days away. I said Okay, we’d send him tickets and money (“With expenses, anything is possible,” Hunter frequently said).” But, seriously, this is some great reporting on the training of cub who would know from Gonzo. Thank you

Crikey I got your name wrong Jerome. Apologies, it’s late and I’m on my second bottle of whiskey …