What the newspaper death notices say about us

Often they are a celebration of a life well-lived as much as a lament for the dead

By DAVID MYTON

Dear Subscribers - I am currently working on an essay in which I examine the “history of history”, otherwise known as Historiography. It’s pretty complicated stuff (especially the postmodern elements) so I probably won’t have it ready until Thursday or Friday this week. In the meantime here is an article I wrote about newspaper obituaries which was originally published by The Sydney Morning Herald some time ago.

In 1973, aged 19, I started work as a junior reporter on a North Yorkshire newspaper. My boss, the news editor, handed me the galley proofs of the next day’s death notices and instructed me to find “a couple of decent stories”.

One of these involved the death of a former local council dignitary. I was told to call his widow to interview her about the achievements of her late hubby. She was more than happy to talk to me so I went to her home.

After asking her a few questions she said to me: “Would you like to see him, love?” I replied that I would, assuming she meant photos. She beckoned me to follow her into the adjacent room – and there was her late husband, laid out in an open coffin, resplendent in Sunday-best suit and new shoes.

“What do you think?,” she asked. I replied that I thought he looked “lovely”.

“Aye, he does that, love. Thank you,” she said.

I often think of her when I read the Sydney Morning Herald’s Saturday deaths and funerals notices.

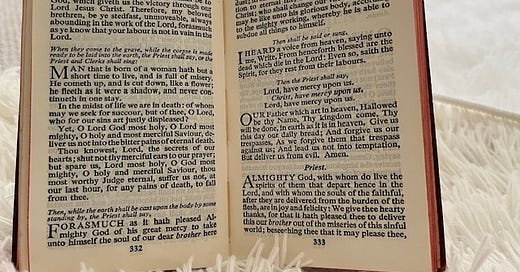

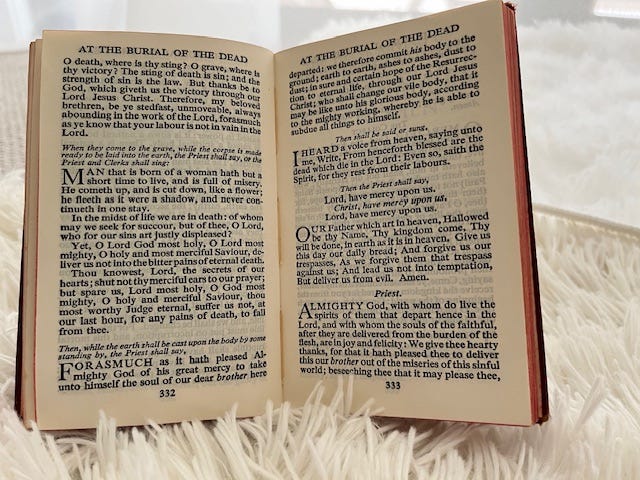

They bring to my mind the old aphorism Media vita in morte sumus – “In the midst of life we are in death”. It’s the centrepiece of a medieval Gregorian Chant, while the Protestant reformer Archbishop Thomas Cranmer ensured it was included in the 1549 Book Of Common Prayer (in which it remains to this day).

Media vita in morte sumus expresses an uncomfortable truth: each and every one of us is, soon or late, going to die.

Readers of Saturday’s The Sydney Morning Herald are reminded of this every week in the Deaths and Funerals section towards the back of the main paper. Here you will find around 70 death and funeral notices set in single column across two to three pages.

My guess is that they are very much viewed, even though there are no shouty 48-point multi-column headlines or award-winning photos and cartoons.

The notices tell a variety of stories, and not necessarily tinged with gloom and tragedy. Often they are a celebration of a life well-lived as much as they are a lament for the dead.

Rarely do the notices speak of material successes. A person’s accumulated wealth, property, and professional achievements are seldom highlighted, as if to affirm the Scriptural wisdom that “we brought nothing into this world, and it is certain we can carry nothing out”.

Rather, they tend to focus on and celebrate family ties, relationships and friendships. They tell of devoted grandparents, mothers and fathers, aunts and uncles, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, nieces and cousins; and of those who were a “loyal friend to many”. Many of the deceased, we learn, “passed away peacefully”.

The notices tell of people who were adored, cherished, beloved, dearly loved, much loved, forever loved, respected, generous, loyal, and devoted. They are sadly or greatly missed. They will be forever remembered.

A number of notices indicate religious ties, especially to Christian denominations encompassing for example Roman Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, and Uniting churches. Occasionally the deceased are said to be “in God’s care”, “at peace with God”, or “with the Lord”.

Age at death is very often recorded in the notices. Mercifully, most fall into the “older” or “elderly” bracket as classified by the OECD – that is, over 65, but more commonly over age 70.

On a recent Saturday I calculated a mean average age of death at 84 years with most clustering in the 80s and 90s, with a couple over 100 years, trailing off through those in their 70s and 60s, with a few in their 50s.

A majority of family names appear to suggest Anglo-Scots-Irish ancestry.

The notices also tell a story about given names popular in a previous era that now appear to be fading to the margins: the likes of Peggy, Edna, Fay, Beryl, Margie, Mollie, Audrey, Colleen, Elspeth, Pam, Joyce, Olive, Gay, Mildred, Maureen, Dawn, Barbara, Janet and Avril; and for men Alfred, Bob, Ken, Bill, Barry, Ron, Albert, Brian, Colin, Keith, Kevin and Harold.

And if for any reason relatives and friends can’t attend the funeral or memorial service, never mind - a growing number of notices indicate the occasion will be live-streamed for their convenience.

There is nothing grand about the Herald’s Death and Funeral notices. But taken together, they possess a simple dignity that honours the deceased.

To paraphrase my comment to that North Yorkshire widow 50 years ago: “They look lovely.”

This article was originally published in The Sydney Morning Herald

Wow David! How traditions change! I've also written about the Dutch death notices by post! They also publish obits and all the names of descendants which remain important I think. Otherwise, seeing bodies seem to be no longer in vogue or restricted. You'd only get to view the closed coffin or the final ceremony with the ashes and urn.

I absolutely agree! I’ve always enjoyed reading obituaries and it has nothing to do with being morbid. It’s just a way of reminding myself that everyone has a story. Thanks for sharing this.