Why the Luddites raged against the machines: they'd seen the future and it didn't include them

In the early 19th century a man with no work was a dead man walking

By DAVID MYTON

Early on Saturday morning January 16 1813 fourteen men - confined by the cold stone walls of York castle prison in the north of England - awaited their imminent execution.

They had earlier been separated into two groups of seven because the gallows wasn't long enough to accommodate all of them at once.

Scores of mounted and foot soldiers patrolled the approaches to the castle while other troops guarded the gallows themselves: this was to be a public execution and the authorities did not want the crowd to get out of control.

At 11am, escorted by the undersheriff and secured by chains, the first seven shuffled onto the gallows while defiantly singing the old Methodist hymn Behold the Saviour of Mankind.

John Ogden, Nathan Hoyle, Joseph Crowder, John Hill, John Walker, Jonathan Dean and Thomas Brooke were then “launched into eternity” as the contemporary saying went - the crowd shrieking in unison as the condemned choked to their deaths.

Their corpses were left to swing on the gallows until noon when they were cut down and taken away.

At 1.30pm the process was repeated: the remaining seven condemned were led to the gallows, again singing a hymn.

In minutes John Swallow, John Batley, Joseph Fisher, William Hartley, James Hague, James Haye and Job Haye were dead - choked on the end of a chain.

These 14 men left a total of 13 widows and 57 children - and we can be sure that life would not be kind to any of them.

Times were changing and not for the better if you were poor.

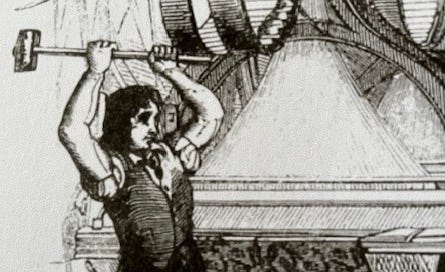

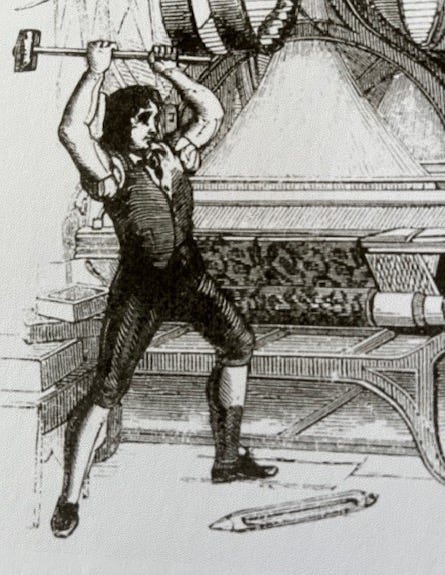

These executed men were Luddites, who along with others on April 11, 1812 had attacked William Cartwright's Rawfolds Mill at Liversedge in West Yorkshire.

Their aim was to smash newly-installed machinery which replaced skilled textile workers who had previously done most of this work by hand or by machines with which they were familiar.

The authorities acted with brutal efficiency to what they saw as a menace and a threat to the good order of society and spared no effort to round up the perpetrators.

Now today the word Luddite is most often used to describe someone who's a bit of a technophobe – they don't like or don't even understand new technology and resist its adoption for as long as they can hold out against the remorseless advance of the new.

But historically it refers to a group of people in early 19th century England who between the years 1811 to 1816 sought to smash and wreck new kinds of machinery installed in mills and factories operating within the textile industry.

They had seen the future and it didn't include them - and back in the early 19th century that was bad news indeed.

A man with no work was a dead man walking.

The Luddite movement first arose in Nottinghamshire and took its name from what seems to be a mythical figure – one Ned Ludd, a kind of latter-day Robin Hood personage, but there's no actual historical record of such a person.

Their fears and anxieties centred on the relentless rise of new weaving machines that would put them out of work.

They sent threatening messages to textile mill owners demanding that such machinery be removed, or at least reduced in number.

When this approach proved fruitless they physically attacked various textile mills and their machinery. Mill owners and other bosses were also targeted with threatening letters and even assaults.

The movement soon spread from Nottinghamshire into Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cheshire among other places. Their attacks were of course illegal - and so was the very act of workers joining together in organizations to further their aims, being proscribed under the Combination Acts passed by Parliament in 1799-1800.

And then in 1809 Parliament completed its de-regulation of the various cloth making industries by abolishing any protection at all for apprentices.

The Luddites’ main objective was to protect their trade and their livelihoods by wrecking “frames” - new and efficient knitting or cloth-finishing machines.

Many of the perpetrators were arrested and tried and - apart from the executions mentioned above - other Luddites were jailed and many exiled by transportation to Australia.

The Government viewed Luddite labour unrest very seriously to the extent that it even mobilised the Army to try to suppress the disturbances: indeed, at one stage there were more soldiers on patrol in Luddite country than there were fighting Napoleon in a serious and major war in Spain.

On February 27 1812 the poet Lord Byron addressed the House of Lords specifically speaking against the new Frame Breaking Act, which mandated the death penalty for wrecking machinery.

Referring to the Luddite actions Lord Byron said these had “arisen from circumstances of the most unparalleled distress”.

Nothing but “absolute want”, he said, could have driven such a large and once honest and industrious body of the people into “the commission of excesses so hazardous to themselves, their families and the community”.

For the mill and factory owners, he said, the new machines were an advantage in as much as they superseded the necessity of employing a number of workmen “who were left in consequence to starve”.

And there we have it - the very root cause of the Luddite upheaval wasn't some technophobic backlash against progress.

Back then if you lost your job, your trade, your income, it could be a death sentence for you and your family. There was no social security safety net, no recruitment firms or job placement agencies; and you couldn't post a “work wanted” ad on LinkedIn.

The Church offered spiritual solace but only minimal practical help because there were no resources to bail people out.

The Luddites wanted to smash and destroy what they called the “obnoxious frames” because they believed they were protecting their trade – which was more than a job; it was a culture, a social identity, a community as much as a technique or a set of work practices.

The renowned English historian EP Thompson in his classic The Making of the English Working Class - speaking of those caught up in the wrong side of the industrial revolution - said this:

“Their crafts and traditions may have been dying; their hostility to the new industrialism may have been backward looking; their insurrectionary conspiracies may have been foolhardy; but they lived through these times of acute social disturbance and we did not. Their aspirations were valid in terms of their own experience.”

The Luddite movement eventually fizzled out with a brief resurgence in 1816-17. The executions, the jailings, and transportation to Australia of captured Luddites really did have an impact.

The historian Martin I Thomas states that it is not reasonable to say that the Luddites of 1812 should have been prepared to ignore their own short-term comforts for the benefit of later generations:

“They operated within their own immediate context and not within the context of long-term industrial development; they were tactically wrong in believing they could successfully resist mechanisation in their own industries; but they were not morally wrong to wish to do this when their very existence might seem to be - and might in fact be – threatened by industrialisation in England.”

The Industrial Revolution was a boon to the capitalists but it was not a good news story for the working class, who found themselves more or less imprisoned in a brutal factory system which only reformed at tortoise-like pace.

REFERENCES

George Gordon Byron, Lord Byron, Speech against the Frame Breaking Act of 1812, House of Lords, February 27, 1812 - https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=4654

ExecutedToday.com, ‘1813: The Yorkshire Luddites, for Murdering William Horsfall’ - http://www.executedtoday.com/2013/01/08/1813-yorkshire-luddites-william-horsfall/

E J Hobsbawm, Labouring Men: Studies in the History of Labour, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1964.

Steven E Jones, Against Technology: From the Luddites to Neo-Luddism, Routledge, New York, 2006.

John McManners, Lectures On European History 1789-1914. Men, Machines and Freedom, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1966.

Malcolm I Thomis, The Luddites. Machine-breaking in Regency England, David & Charles Archon Books, 1970.

E P Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, Gollancz, London, 1963.

‘York and the Luddites’, York alternative history blog https://yorkalternativehistory.wordpress.com/write-it/york-and-the-luddites-1813/