Why YouTube Bible experts Ehrman and Tabor (and the rest) owe it all to the Germans

Uncovering the foundations of today's on-line Scripture scholarship

By DAVID MYTON

In a nerdy corner of YouTube many thousands of people congregate to listen to experts talk about the Christian Bible. Scholars such as Bart Ehrman, James Tabor, Mark Goodacre, Francesca Stavrakopoulou, Elaine Pagels and Tom Holland analyse and explain the Scriptures, discuss who might have written them, and for what purpose.

That all this is enabled by the Internet and technologies of film and podcasting suggests it is something trendy and modern – but they owe it all to the labours of obscure theologians hundreds of years ago in what today is Germany.

These Bible scholars have bequeathed to us ideas much discussed by the YouTube theologians such as the Documentary Hypothesis, Form Criticism, Redaction Criticism, the Marcan Hypothesis; and the notion of “Q” (from the German word Quelle) - a purported source document for the Gospels.

Collectively this enterprise is known as Biblical Criticism, in which criticism is derived from the word’s Greek root krinein, suggesting something akin to analysis: to discover a text’s original meaning in its historical context.

Disenchantment … the historical and social setting

In the wake of the Reformation and Enlightenment, many scholars argued that Scripture ought to be subject to the same scrutiny as that applied to secular writing.

This was part of a process the German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) termed Entzauberung (disenchantment): that traditional elements of knowledge – such as theology and metaphysics - were being pushed into the realm of the superstitious, the mystical, and the irrational.

For most Europeans during the 16th-18th centuries, cultural and intellectual life was anchored in the Roman Catholic Church, which was “priest-centred, highly sacramental [and] dependent particularly on confession and communion as routes to salvation”, writes historian R N Swanson. (Authors and books referenced are listed at the end of this article)

The Protestant Reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin were to change all that.

The Bible, understood as the inerrant word of God, was to be the central pillar of faith: and faith alone (Sola fide) the key to salvation, not “good deeds”.

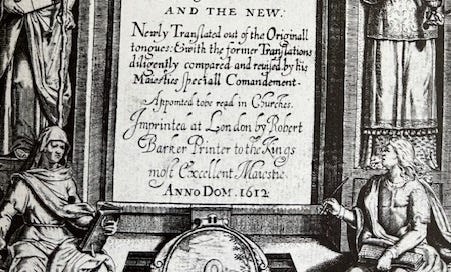

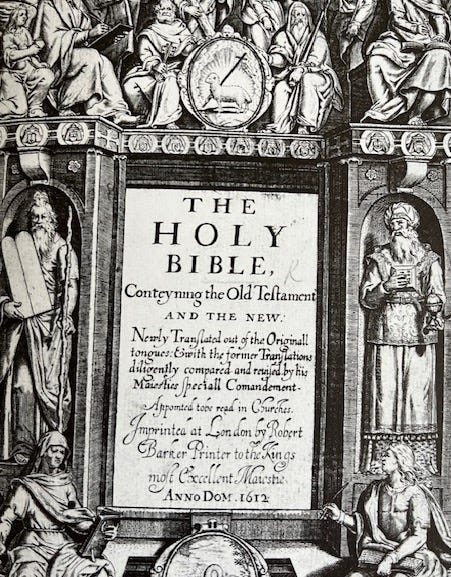

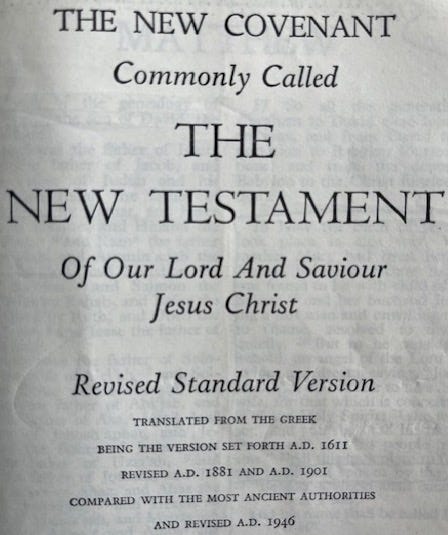

In 1522 Luther published his German translation of the New Testament and by 1534 he had also translated the Old Testament. Protestants went on to make translations of the Bible that were not based on the Latin medieval Vulgate but on texts of the Bible in Koine Greek and Hebrew – its original languages.

Increased scepticism and the marvel of movable metal type

The revolution in printing sparked by Johannes Gutenberg’s invention in the 14th century of movable metal type ensured increasing numbers of books were available across Europe. Literacy rates grew and more people had the opportunity to own and to read their Bible without it being mediated by a priest.

The Old Testament scholar Professor R K Harrison argues that the importance of the Reformation for Biblical criticism lay “in the continued insistence upon the primacy of the simple grammatical meaning of the text in its own right independent of any interpretation by ecclesiastical authority”.

Increased reading of the Bible in the local language boosted literacy rates, equipping more people to investigate Scripture for themselves.

However, there was a growing scepticism about religion. For example, philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) argued religious faith was “a mere compound of credulity and prejudices and a tissue of meaningless mysteries”.

The Bible, he said, should be seen as the product of primitive human spiritual development. The Israelites had called any phenomenon they could not understand God, said Spinoza.

In France, philosopher Denis Diderot (1713-1784) wrote that whether God existed or not He had come to rank “among the most sublime and useless truths”.

Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-72) argued that God was simply a human projection. And Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) declared there was “no absolute, no reason, no God, no spirit, at work in the world – nothing but brute instinctive will to live”.

Politics and economics began to displace religion among intellectuals. Karl Marx (1818-1883) and colleague Friedrich Engels (1820-1895) focused on economics and the structure of work and society. “Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless condition. It is the opium of the people,” Marx said.

Then in 1882 philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche announced that God was dead … “We have killed him, you and I. We are all his murderers.”

Religious faith was also tested by the revelations of science. For example, Nicolas Copernicus in 1530 and Galileo Galilei in 1613, utilising the new telescope, revealed the Sun was the centre of the universe and that Earth and other planets revolved around it - contrary to the teaching at the time.

This got them into trouble with the Inquisition because it contradicted the longstanding geocentric model. But as Armstrong points out, the heliocentric theory was not condemned because it endangered belief in God, but because it contradicted the word of God in the Scriptures.

Rationalism, reason, and empiricism: the new Bible Critics

This was the context in which the new Bible scholars emerged in what today is Germany. For many of them, rationalism, reason, and empiricism subordinated faith.

One frontrunner in the new Biblical criticism was the Prussian poet J G von Herder (1744-1803) – an Old Testament scholar who based his observations about Scripture in the context of ancient Near Eastern culture.

Herder applied secular interpretative methods to identify and define different genres of poetry in the Old Testament and argued against allegorical interpretations

Influenced by Herder, J G Eichhorn (1752-1827) wrote several influential new introductions to Old Testament scriptures in a three-volume work published between 1780-83. Much of the Old Testament writings, he declared, “displayed more of the character of Hebrew national literature than what might be expected to constitute Holy Scripture”.

Eichhorn also doubted that the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible) was written by a single author, as then supposed. There was too much variation in form and style, he argued.

Instead, he proposed the “Documentary Hypothesis” arguing that the book of Genesis was composed by combining two identifiable sources – the Jehovist (J) also known as the Yahwist (Y) and the Elohist (E). These were different names of God used by various OT authors.

(Incidentally the name Yahweh is a rendering of the so-called Tetragrammaton YHWH, which is how God’s name appears at places in the Bible. Old Hebrew was written without vowels, only consonants.)

Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834), instrumental in the development of liberal Protestantism, embarked on a quest to develop new modes of interpreting and understanding the Bible.

Schleiermacher, writes R K Harrison, sought “to ransom Christianity from complete rationalism by introducing the concept of mystical subjectivism”, which examined human feelings or emotional reactions involving religious phenomena.

Revelation, then, was not a disclosure of fundamental truth from God to people but “represented the progress of humanity towards a consciousness of God”. Dogmas, said Schleiermacher, were not divine facts but “simply accounts of the Christian religious affections set forth in speech”.

Also significant is Hermann Gunkel (1862-1932) - the so-called Father of Form Criticism. Gunkel had observed the work of the Brothers Grimm – the collectors and compilers of fairy tales – and noted that many of these stories were comparable in form to the Biblical narratives writes Stanley E Porter in his Dictionary of Biblical Criticism and Interpretation.

Gunkel concluded that Grimm’s tales suggested an original oral context of passages in the Pentateuch. Gunkel worked to place verses in Genesis and Psalms into their “forms” - whether they were poetry, morality tales, prayers, and the like. They then could be placed within their Sitz im Leben – situation in life – to understand their lived meaning.

Another important scholar is Julius Wellhausen (1844-1918), described as a man of wide spiritual vision with a brilliant and penetrating mind. Wellhausen’s so-called Historical Criticism or Higher Criticism investigated the origins of ancient scriptures in order to understand “the world behind the text”.

In his 1875 work Prologema to the History of Ancient Israel Wellhausen argued that four major documents could be detected in the Pentateuch – a theory known as the Documentary Hypothesis. Each was subtly different, he said, and had been interwoven into the Biblical documents by a series of editors thus merging elements of law, covenant, religion and history to one comprehensive scheme.

Scholarly critics turn their eyes to The New Testament

Two major elements of scholarly criticism of the New Testament flowered in this time – Redaction and Form Criticism.

A major player in the origins of these analytical models was Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694-1768), a professor of Oriental Languages in Hamburg.

According to Norman Perrin from the University of Chicago’s Divinity School, Reimarus felt the Gospels were not historical since they reflected concepts developed long after the events they narrate took place.

Similarly, David Friedrich Strauss (1808-74) argued that the Gospel accounts could not be understood as historical, but instead were “concerned with purveying a Christ myth”.

Later New Testament scholars, however, felt it should be possible to know Jesus “as he actually was” through the Gospels. This so-called Life of Jesus movement aimed to dismantle the “Christ of Faith” and separate that from the “Jesus of History”.

Out of this quest they developed a new literary critical insight – that Mark was the earliest Gospel and a source used by Matthew and Luke.

One of these scholars was the Protestant theologian Heinrich Julius Holtzmann (1832-1910) whose The Synoptic Gospels: Their Origins and Historical Character argued that Mark was the earliest Gospel and closest in time to the original witnesses, and so could be used as a historical source for knowledge of Jesus’ ministry.

With the works of Protestant theologian Martin Dibelius (1883-1947) with From Tradition To Gospel and Rudolph Bultmann (1884-1976), with The History of the Synoptic Tradition a new discipline – formgeschichte, or Form Criticism, proposed that most of the stories and sayings of Jesus were first circulated in small independent units.

These self-contained stories could be classified according to literary form or type, he said, and may have been used by the early Church in preaching and teaching. The miracle stories, for example, extolled Jesus as a wonder worker.

Out of Form Criticism flows another notion, that of Redaction Criticism, in which redaction means editing and composing – viewing the Gospels as literary works in themselves.

In this view, the Evangelists are seen not as collectors and handers-on of their material, but instead are authors who by selecting and editing their material impose a distinctive theological stamp.

As Ralph P Martin writes, “we are encouraged to enter and explore the world of the evangelist himself, and seek to understand what the Gospel stories would have meant in those original settings”.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke … the Synoptic Problem

Important in New Testament studies is the so-called Synoptic Problem – basically, what accounts for the similarities and differences between the three Synoptic gospels Matthew, Mark, and Luke.

One of the earliest uses of the word synoptic, as it relates to the Bible, was by the German Biblical scholar J J Griesbach (1745-1812) to mean that the first three Gospels could be “viewed together” – having basically the same point of view as opposed to the totally different standpoint of John’s Gospel.

He suggested that Matthew was written first, followed by Mark and Luke – in this view, the second writer drew on the work of the first and the third writer on the work of the preceding two.

Then in 1889 theologian Heinrich Julius Holtzmann argued that the foundation Gospel was Mark since both Matthew and Luke incorporate almost all of Mark - but Matthew and Luke utilised another hypothetical written source, designated Q from the German word for source, Quella.

This is just a brief sketch (really!) of the development of Biblical criticism. If you are interested in this topic then the YouTubers mentioned in the intro are excellent sources of information.

References

Karen Armstrong, A History of God. The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, Ballantine Books, New York, 1993.

G W Bromley, ‘The Authority of Scripture’ in New Bible Commentary, Third Edition, Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester, England, 1970.

Christopher De Hamel, The Book: A History of The Bible, Phaidon Press, 2001.

Mark S Goodacre, The Case Against Q: Studies in Markan Priority and the Synoptic Problem, Trinity Press International, Harrisburg, PA, 2002.

R K Harrison, Introduction To The Old Testament, William B Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1969.

Harry Hearder, Europe in the Nineteenth Century 1830-1880, Longman, New York, 1991.

D Edmond Hiebert, An Introduction to the New Testament, Vol 1 The Gospels and Acts, Moody Press, Chicago, 1975.

Kim, Sung Ho, ‘Max Weber’, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.) https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/s...

W G Kummel, Introduction to the New Testament, Abingdon Press, 1996.

Ralph P Martin, New Testament Foundations. A Guide For Christian Students. Volume 1, The Four Gospels, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1975.

Norman Perrin, What is Redaction Criticism?, Fortress Press, Philadelphia, 1969.

Stanley E Porter, Dictionary of Biblical Criticism and Interpretation, Routledge 2009.

Agatha Ramm, Europe In The Nineteenth Century 1789-1905, Volume One, Longman, New York, 1984.

RN Swanson, Religion and Devotion in Europe c 1215-c1515, Cambridge Medieval Textbooks, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Allen & Unwin, London, 1930.

Walther Zimmerli, Old Testament Theology In Outline, John Knox Press, Edinburgh, 1978.