By DAVID MYTON

What is History? Silly question, because it’s obvious isn’t it … it’s the factual record of the lives and times of the people of the past: dates and battles, kings and queens, explorers, soldiers, men and women achievers of one sort or another, that kind of thing.

Well, yes - but wait. History is the recorded past, not the past itself. So how do historians access those records and how do they know they are genuine? How do they decide what to leave in and leave out? How do they determine accuracy? How do they know the documents are real, that the people being written about actually existed? If they existed but did nothing “notable” are they worth recording? And how do we know we can even trust the historians’ conclusions?

As historian David Thomson writes: “The past is dead but not done with. It is dead because it cannot now be changed in any detail whatsoever. It is not done with because its relics and consequences surround us in our daily lives and it is believed, and with good reason, to matter to us greatly.” (The Aims Of History. Values of the historical attitude, Thames and Hudson, London, 1969, p17)

History is not merely “one damned thing after the other”. Indeed, there is a history of History itself, and that process is Historiography - which I will be examining in this essay. However, this is an introduction to Historiography, just the first in an occasional series spread over the next several months.

Traditionally, the delivery of History in the West has occurred via manuscripts and books written chiefly by monks and scribes, then later academics and scholars. But recent years have seen the rise of new delivery media - the podcast and YouTube videos.

Those by the likes of Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook (The Rest Is History), James Holland and Al Murray (We Have Ways Of Making You Talk) - all reputable historians - are certainly educational but they are also entertainment. To my mind redolent of the sagas and poetry dramatically spoken in the mead halls of Early Medieval Britain and Continental Europe. There are also numerous channels and film documentaries dedicated to the history of war - especially, but not solely, World War 2 - and these show no sign of a decline in popularity. What will be their place in Historiography?

Perhaps historian Beverley Southgate is correct when she says: “It’s possible now to identify numerous threats to the discipline of history in its traditional form … The other country of the past may have long been colonized by historians and adopted as their own, but there are many other claimants to that territory, and the age of academic imperialism has passed.” (What Is History For?, Routledge, Oxon, 2005, p133)

In this essay - the first in an occasional series - I will be looking at the development of Historiography in the British-European context, with the major focus being on the 17th-19th centuries: an epoch of substantial and significant change in the study of History.

Mind and discourse dependent

Today there is a widespread belief that historians cannot represent the past as it truly was “They can only take control of it through their preferred theory of knowledge and/or perception,” writes Professor of History and Historical Theory, Alun Mounslow. (The New History, Pearson Education, Harlow 2003, p4-5)

History, he says, is a “mind and discourse dependent performative literary act” in which historians “ascribe meaning to the past” rather than discover its “inherent meaning”.

The Modernist idea of “truthful interpretation” should now be replaced by the more “helpful notion of history as a form of representation”.

“Modernist” history - a model of history that evolved from ancient times to become “professionalised” in the 19th century - assumed that past “reality” could be retrieved by neutral historians, be viewed objectively, and revealed as “truth” about the past within a well-constructed narrative.

In this view “it is the task of the historian to describe, as accurately as possible, former states of the world”, writes Michael Stanford. (An Introduction to the Philosophy of History, Blackwell, Oxford, 1998, p12)

In the words of the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga: “If the deeply sincere desire to to find out how a certain thing ‘really happened’ is lacking … [the writer] is not pursuing history”, (cited in Southgate, op cit, p14)

But is past reality already a narrative? Does it somehow exist as a “story”? Do events and human actions carry within themselves an intrinsic narrative shape? Not really.

Historians provide the narrative, the shape, the representation. And the historians’ education and mindset “whether they choose to acknowledge them or not, are always the filter through which their epistemology works and their factual statements and narratives are written”. (Mounslow, pp13-14)

Around 300 years ago it was assumed that “facts” could be discovered in the records, and then be woven into a narrative that represented the past - a past over which God had been, and still was, in charge.

The greatness of the Almighty

Writing in the early 18th Century the then-popular French historian Charles Rollin (1661-1741) declared that History “proclaims universally the greatness of the Almighty, his power, his justice, and above all the admirable wisdom with which his providence governs governs the universe”. (Rollin, The Ancient History … Ward Lock, London, 1881 piii, cited in Southgate, op cit, p50)

This was a common view throughout northern Europe which had been held, in one form or another, since the widespread conversion to Christianity across the Continent in the early centuries of the Common Era.

For example, in the Venerable Bede’s A History Of The English Church and People, written in the 8th Century CE, and Geoffrey Of Monmouth’s The History Of The Kings Of Britain (12th Century CE) references to God/Jesus are common in both narratives. Indeed, the Devil also makes at least one appearance in Bede’s History during a guided tour of Hell narrated by one character. And the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, compiled by monks over several centuries to 1154CE, are interlaced with religious themes throughout.

As I have pointed out in my post on Martin Luther and the development of printing, the Bible was understood by most Medieval-era readers as narrating factual history that in itself proclaimed the greatness of God and to which Jesus Christ gave meaning. Indeed, Jesus himself appeared to authenticate this view, declaring that Scripture itself had foretold his mission in… “everything written about me in the law of Moses and the prophets and the psalms” and which foretold his destiny … “it is written that Christ should suffer and on the third day rise from the dead...” (Luke 24, v44 v46)

Literacy rates across Europe shot up as more people were able to read the Bible for themselves as well as texts written by monks and other clergy. Many educated citizens would also be familiar with early Greek and Latin historical-religious narratives. Men wrote histories that proclaimed the greatness of a God who oversaw the running of reality.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) famously wrote the past into his plays, which more often than not featured real historical characters speaking the playwright’s sublime (but invented) verse and prose at a time when factual accuracy was not deemed to be necessary.

However, the English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561-1626) presaged new trends in thinking when he declared: “The philosophic doubt is the beginning of the search for truth.” (cited in David Thomson, The Aims Of History. Values of the historical attitude, Thames and Hudson, London, 1969, p83).

Introducing the Enlightened

A major shift occurred in the late 18th Century with the advent of the Age of Enlightenment. Across Europe, especially in France, Germany and Britain, philosopher-scholars began to look at History in new ways, presaging modern methods of historical investigation.

On a practical level, for example, the University of Gottingen’s History school in 18th Century Hanover had accumulated massive numbers of documents and texts cluttered randomly in their archives.

Motivated by a desire for accuracy and method, scholars examined and classified the documents “with the most meticulous scholarship and critical apparatus” with the aim of eliminating “the haphazard and the slipshod from historical learning, to destroy inaccuracy and error, to provide history with a firm bedrock of proven and verifiable facts …setting a new standard of scholarship”. (Thomson, op cit p38)

This practical achievement was a reflection of Enlightenment rationalism and empiricism aimed at “discovering the true nature of reality through the application of inductive and deductive reasoning, and then representing it accurately … Rationalism holds the view that it is feasible to discover truths about the character of reality by the application of reason.” (Munslow, op cit, p30)

The work of the English polymathic scientist Sir Isaac Newton (1643-1727) underscored the new importance of empirical investigation and “the application of reason”.

Mathematics key to the physical world

Newton with his great work The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (aka Science) demonstrated how mathematics is the key to the physical world. He invented calculus and revealed the structure and forces of the solar system … “The essential revolutionary element was that Newton had conceived a working universe wholly independent of the spiritual order”. (Charles Singer, A Short History of Scientific Ideas to 1900, Oxford University Press 1959, cited in Michael Stanford, An Introduction to the Philosophy of History, Blackwell, Oxford, 1998, p155)

Newton didn’t intend it, but “the conflict between science and religion began and raged on for centuries”. Stanford, op cit p155)

New ways of looking at history emerged. For example, the French thinker Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet) in works such as The Age of Louis XIV (1751), and Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations (1756) broke away from the then-standard military and diplomatic narratives to focus on topics including social history, customs, culture, the arts, politics, economics, and world history.

“You have to write history like a philosopher,” he said. “My chief object is not political or military history, it is the history of the arts, of commerce, of civilization - in a word - of the human mind.”

(Michael Stanford, An Introduction to the Philosophy of History, Blackwell, Oxford, 1998, p15)

One of the most remarkable of the Enlightenment philosopher-historians was René Descartes, author of the highly influential Discourse on Method (1637) - from which his famous I think, therefore I am epigram is first stated.

Descartes is important to Historiography because he stimulated new ways of thinking and addressing concepts of knowledge and truth. Reasoning, he said, should begin with the author doubting all existing knowledge, in order to approach their subject as a neutral observer free of preconceived ideas. “He resolved ‘never to accept anything as true if I had not evident knowledge of its being so’,” he said. (Descartes cited in Stanford, An Introduction to the Philosophy of History, op cit p6)

The examination of causality

Another Enlightenment philosopher Montesquieu (1689–1755) - again influenced by the rise of science - argued in his 1748 book The Spirit of Laws that economies and political systems could be explored by examining causality: for example, the larger the country the more its rulers would incline to despotism; republics should be ruled small governments; while large countries such as Russia required despotism; although constitutional monarchy was ideal for stable, smaller states). Montesquieu’s notion of small government was influential on America’s Founding Fathers.

One of the most influential figures to emerge later in this time was the German philosopher Georg Hegel (1770-1831) who developed the concept of Zeitgeist (spirit of the age). “Whatever happens,” he wrote, “every individual is a child of his time; so philosophy too is its own time apprehended in thought.” And so the Historian is a “child of their time”, thinking the thoughts of the current zeitgeist.

The “greatest historian” of the time, Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886), placed a similar emphasis on the spirit of the age - “Every epoch is immediate to God and its worth rests in its own existence, its own self,” Ranke wrote.

Observes the historian Michael Stanford: “Here again we see a well-founded belief about the human individual (the belief, common to great religions as well as to secular humanism, of the inherent value of every man and woman) being illegitimately transferred to a notional construct - this time the age. In fact, Ranke did hold similar (surely unjustified) belief about states, which are ‘thoughts of God’.’ (Stanford, op cit, pp158-159)

In England the philosopher-historian David Hume (1711–76) rejected grand, overarching narratives but embraced empiricism in his History of England (published in six volumes between 1754–62) from the invasion of Julius Caesar in 54BCE to the Revolution of 1688 about which he wrote: "By deciding many important questions in favour of liberty, and still more, by that great precedent of deposing one king, and establishing a new family, it gave such an ascendent to popular principles, as has put the nature of the English Constitution beyond all controversy".

A new approach to writing history

One of the most outstanding Enlightenment historians was Edward Gibbon (1737–94), who in his six-volume The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–88) displayed, according to David Thomson, an “ironic rationalism that marked a new approach to the writing of history … Gibbon broke dramatically from the powerful theological tradition of western culture. His ironic rationalism marks a new approach to the writing of history.”

“Gibbon dismissed the providential approach to historical explanation, and took his stand on the analytical, secular historical attitude favoured by most modern historians. Their concern is not with divine purpose or miraculous interventions, but with those secondary causes - the interplay of personality, ideas, conditions and events which can yield some description and explanation of the fascinating process of historical change.” Thomson, The Aims Of History, pp 64-65)

As Gibbon himself noted: “To the believer all religions are equally true, to the philosopher, all religions are equally false, and to the magistrate, all religions are equally useful.”

This ends this introductory essay to the history of Historiography. I have barely scraped the surface of the topic but I hope it serves as some initial guide to the development of the discipline of History, especially in the pivotal years of the European Enlightenment.

I plan to develop the subject over the next few months, examining various aspects of Historiography including Marxist and Postmodernist approaches to history.

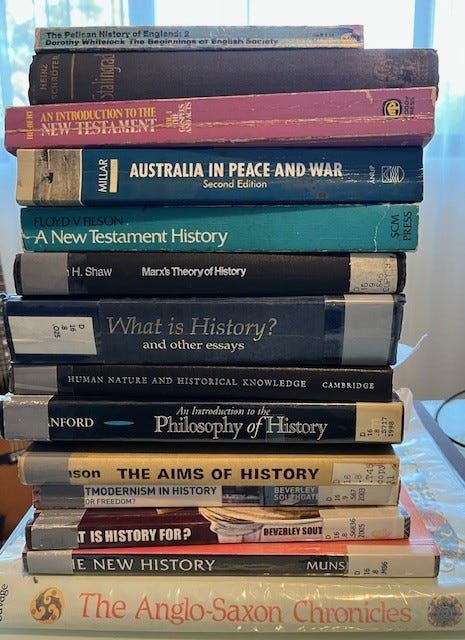

REFERENCES

Alun Mounslow, The New History, Pearson Education, Harlow 2003

Michael Oakeshott, What is History? And other essays (ed Luke O’Sullivan), Imprint Academic, Exeter, 2004

Leon Pompa, Human Nature And Historical Knowledge. Hume, Hegel and Vico, Cambridge University Press, 1990

William H Shaw, Marx’s Theory Of History, Hutchinson, London, 1978

Beverley Southgate, Postmodernism In History. Fear or Freedom, Routledge, London, 2003

Beverley Southgate, What Is History For?, Routledge, London, 2005

Michael Stanford, An Introduction to the Philosophy of History, Blackwell, Oxford, 1998

David Thomson, The Aims Of History. Values of the historical attitude, Thames and Hudson, London, 1969

Thanks for this essay, David. I’ve been particularly interested in digging deeper into historiography lately, and this was a thoroughly engaging overview of the subject. I especially appreciated the framing of historiography as not merely a quest for “what happened,” but as an evolving dialogue shaped by epistemology, narrative, and power. I’m very much looking forward to the continuation of this series.

I’m so excited to follow along with this series! I feel like it’s become vogue to focus on the ways we cannot understand the past because of our modern conceptions, but that is so frustrating! Then again, who can say that there ever was an objective “truth” in the world? We can say “this person certainly lived this year, they did this, and they died then” but is this data collection the purpose of history?