By DAVID MYTON

On February 17 1600 Giordano Bruno, naked, hands bound behind his back, was led out onto Rome’s crowded Piazza Campo de’ Fiori where he was tied to a large wooden stake and then burned to death. It would have been a ghastly sight, Bruno writhing and screaming until mercifully he passed out, choking on the smoke as his life turned to ashes.

When it was all over the crowd dispersed to go about their business. It was just another day in Rome. There was to be no grave for Bruno - his ashes were unceremoniously dumped in the River Tiber.

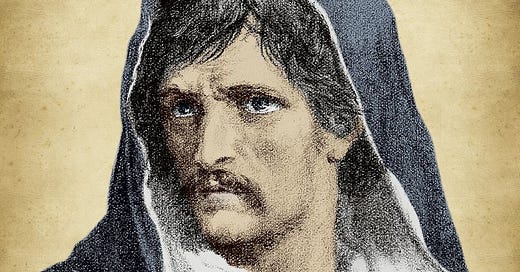

Bruno, polymathic philosopher, astrologer, poet, pantheist, and well-travelled teacher, had been convicted of heresy and blasphemy by the Roman Inquisition.

His alleged sins included support for the Copernican heliocentric model of the universe, belief in the plurality of worlds, and holding opinions contrary to the teaching of the Catholic Church on matters such as transubstantiation and the Mass.

Chief Inquisitor Cardinal Robert Bellarmine - later to be involved in the Galileo heresy case (see my recent essay on this subject) - called on Bruno to recant his beliefs. He refused. The matter was passed on to Pope Clement VIII who on January 20 1600 declared Bruno a heretic and sentenced him to death.

He wasn’t the first, and he wouldn’t be the last.

Death by fire the standard punishment

What is the context for this horrific event?

The Roman Inquisition was established by Pope Gregory IX in Toulouse in 1233, staffed by the Dominican Brothers who were given legal authority to convict suspected heretics without any possibility of appeal - “and thus, in effect, to pronounce summary death sentences”. (Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, The Inquisition, Viking 1999. See References below for full details of works cited).

Ironically Bruno was a Dominican Brother for many years.

“According to the Roman legal code, death by fire was the standardised punishment for parricide, sacrilege, arson, sorcery and treason. Herein lay the precedent for dealing with heretics,” they write.

Over time the Inquisition was established in other domains. Perhaps the most notorious of these is the Spanish Inquisition, set up by the Spanish Monarchs Isabella and Ferdinand in 1478. It was not an instrument of the papacy but “functioned as an instrument not only of ecclesiastical orthodoxy, but of royal policy as well”. (op cit, p63-64)

Taking into account all the Inquisition tribunals in Spain up to about 1530 “it is unlikely that more than two thousand people were executed for heresy by the Inquisition”, writes Henry Camen (The Spanish Inquisition. A Historical Revision, Yale University Press, 1998, p60).

“The final death toll may have been smaller than historians once believed, but the overall impact was certainly devastating for the cultural minorities most directly affected,” he adds.

The Roman Inquisition - a tribunal responsible to the Holy See - was established in the 16th Century with the aim of prosecuting people suspected of offences such as blasphemy, witchcraft and heresy across Italy, Malta and other areas in Europe under papal jurisdiction.

Historian Andrea Del Col estimates that out of 62,000 cases judged by Inquisition in Italy after 1542 around 2 per cent (1,250) ended in death sentences.

(For details on the Church’s role in the persecution and murder of so-called witches in Europe, check out my article here.)

Challenges for Christianity’s accepted order

All of this was taking place in a time of slow but ineluctable change which saw the rise of Protestantism, bringing with it new challenges for Christianity’s established order.

For example, on October 31 1517 the monk Martin Luther, angered at the selling by clergy of so-called “Indulgences” - which promised remission from punishments for sin - published his “95 Theses”, condemning this practice and what he saw as various Papal abuses.

Luther argued that people could only be “saved” not by their deeds or “good works”, but by “faith alone” and through God’s grace. He was excommunicated from the Church and when he refused to recant he was declared an outlaw and heretic.

In 1534, Luther translated the Bible into German, arguing that people should be able to read the Scriptures in their own language as the Bible was the Inspired word of God. They didn’t need a priest to help them.

Luther, writes Amir Alexander, sealed the fate of Christendom. “For over a thousand years the Roman Church had reigned supreme in western Europe:

“It had witnessed the rise and fall of empires, invasion and occupation by infidels, heresies large and small, plague and pestilence, and ruinous wars of king against king and emperor against pope.

“From baptism to last rites, the Roman Church oversaw the lives of Europeans, giving order, meaning, and purpose to their existence, and ruling on everything from the date of Easter to the motion of the Earth and the structure of the heavens … the fabric of life itself was inextricably bound to the Roman Church.

“But when Luther took his stand at the Diet of Worms, this cultural unity came to an abrupt end. By proudly proclaiming his heretical beliefs, he renounced the authority of the Roman Church and led his followers along a new religious path … The spiritual unity of the West was shattered with one blow …” (Amir Alexander, Infinitesimal. How a Dangerous Mathematical Theory Shaped the Modern World, Oneworld, London, 2014, pp24-25)

Also advancing the Protestant cause came John Calvin (1509-1564) whose The Institutes of the Christian Religion gave expression to a new vision for Christianity that emphasised the reading of Scripture, personal faith, an argument for predestination - and that grace is a gift from God.

However, the Puritans, as they became known, also had a heavy emphasis on hell and damnation combined with an intense self-scrutiny … but on the positive side “it gave people pride in their work, which hitherto been been experienced as slavery but which was now seen as a calling …”

Religious affairs writer Karen Armstrong says the 15th and 16th centuries “were decisive for all the people of God … and it was a particularly crucial period for the Christian West, which had not only succeeded in catching up with [the world’s] other cultures but was about to overtake them…” (A History of God, Ballantine Books, New York, 1993, p257, p284)

To be truly a Christian in this era was “not merely a matter of internalised spirituality, but of external conformity. Small deviations from accepted social practice were sufficient to mark anyone as of uncertain faith”, writes R N Swanson (Religion and Devotion in Europe c.1215-c.1515, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995, p312)

Christianity, on its own terms and premises, was perfectly rational from Biblical givens which were thought to be undeniably historical, Swanson says, adding:

“The church had to supply a satisfactory code of moral, religious, and spiritual obligations: one not so demanding that it repelled, nor so undemanding that it offered no challenges; not so complex that it was impractical or incomprehensible, nor so simplistic that it could not satisfy needs for self-assurance… [it was] consistently a demand-led religion [in which] individuals invested effort, money, hopes, in return for rewards and benefits; producing an economy of salvation which ultimately embraced all who accepted the faith.” (op cit p316)

Swanson writes it was unlikely that there were many - if any - actual atheists.

“The period’s cosmological perceptions made atheism perhaps the most irrational of stances, opposing all received notions of creation, of human organisation, and of future destinations … vocal opposition to the church’s established structures and beliefs was very much a minority affair …” (ibid, pp 339-340)

The Inquisitor who lived in poverty and died a pauper

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, the Inquisitor, and Giordano Bruno, the heretic, had at least one thing in common: both were highly intelligent and educated men. Aside from that, they were polar opposites.

Bellarmine, who died in Rome aged 79 in September 1621, was a lifelong man of the Church. A Cardinal, he was declared a Saint in 1930 - you can read his biography in full here.

Bellarmine, a Jesuit, was a theologian who had a deep empathy for the poor to whom he donated most of his income. He lived in virtual poverty and died a pauper.

He wrote an astonishingly erudite five-volume book - De Controversiis - published in Latin in 1588. In it he displays a deep knowledge of the Bible. He employs numerous verses from the Scriptures to support his arguments rebutting various Protestant claims, and also in explaining the theological basis of the Papacy. (I borrowed a copy of the book from Macquarie University Library in Sydney.)

Bellarmine in 1615 became involved in the Galileo case in which he treated the scientist with dignity and respect. In short, he rejected the Heliocentric argument but urged Galileo to advance it as a hypothesis. He had died by the time the Inquisition investigated (and condemned) Galileo again in 1623.

Bellarmine was a Church man to his core. He lived for his religion (in his view the one true faith), and he believed in the words of the Holy Scriptures. For example, he spends several chapters in his book rebutting Protestant claims that the Pope is the Antichrist (Bellarmine routinely calls Protestants “heretics”):

“The name ‘Antichrist’ can not mean Vicar of Christ in any manner, rather, it merely means someone contrary to Christ; not contrary in any way whatever, but so much so that he will fight against that which pertains to the seat and dignity of Christ; that is, one who will be a rival of Christ and to be held as Christ, after he who truly is Christ has been cast out.”

(St Robert Bellarmine (trans Ryan Grant) De Controversiis: Tomus 1 p331).

At the Inquisition hearing, Bellarmine demanded Bruno recant his contrary opinions on the Church’s teachings and other matters, but Bruno refused. On January 20 1600 Pope Clement VIII pronounced Bruno a heretic. He was sentenced to death.

Bruno: too clever for his own good

Although extremely intelligent, Bruno was too clever for his own good. To be sure, he was smart, but he lacked wisdom and good judgement. He was not living in an era of free speech and free thought. Today he would be the vibrant host of some wacky science-based YouTube channel; but back then his future prospects didn’t look good.

An Italian born in 1548, Bruno was a pantheist, poet, philosopher, astrologer and apparently even dabbled in alchemy. On top of this, he was an hermeticist - a follower of Hermes Trismegistus - and a keen observer of the night sky.

He speculated that some stars may be planets, and subscribed to the Copernican view that the Sun was the centre of the universe, and that the Earth orbited around it.

In April 1583 he travelled to England and for a time lectured at Oxford University. He wrote a number of books including The Ash Wednesday Supper, On Cause, Principle and Unity, On the Infinite, Universe and Worlds, and The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast.

Later he travelled to Germany where he lectured at Wittenberg University. More books followed including On Magic and Theses On Magic.

In 1592 he moved to Venice where he was overheard discussing some of his more extreme ideas and was denounced to the Venetian Inquisition. Some months later he was packed off to explain himself to the Rome Inquisition, and was imprisoned in the Tower of Nona. His trial soon followed.

Explaining the inexplicable

For many today the Inquisition seems inexplicable, beyond reason and understanding. How could they burn somebody just for having new and unusual ideas that are simply accepted as part of reality today? It seems barbaric.

But as the cliche has it - the past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.

Historians Sonke Neitzel and Harald Welzer write that humans never act on the basis of objective conditions - rather, people interpret what they perceive and on the basis of interpretation draw conclusions, make up their minds and decide what to do. (On Fighting, Killing and Dying. Soldaten. The secret World War 2 transcripts of German PoWs, Random House, 2012.)

However, they say, the ability to interpret and decide what one is dealing with requires a “frame of reference” which provides orientation.

Such frames of reference vary according to historical periods and cultures, but it is difficult to interpret what we see outside of references not of our choice or making.

When we want to explain human behaviour, they say, we first must reconstruct the frame of reference in which given human beings operated, including which factors structured their perception and suggested certain conclusions …

“When frames of reference are ignored, academic analysis of past actions automatically becomes normative, since present day standards are enlisted to allow us to understand what is going on.”

It is only in retrospect that developments appear inevitable and compulsory. “While they are still developing, social processes contain a rich variety of possibilities, of which only a handful are taken up, and they in turn create certain path dependencies and a dynamic of their own.”

And that’s the key … in trying to understand the past we need to use our imaginations to try to perceive it as the people of the time did.

It is easier to judge than to try to understand.

REFERENCES

Amir Alexander, Infinitesimal. How A Dangerous Mathematical Theory Shaped The Modern World, Oneworld, London, 2014.

Karen Armstrong, A History Of God. The 4,000-year quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, Ballantine Books, New York, 1993.

Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, The Inquisition, Viking, London, 1999.

Paul Davies, The Mind Of God. The Scientific Basis for a Rational World, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1992.

St Robert Bellarmine (trans Ryan Grant), De Controversiis: Tomus 1. On The Roman Pontiff, Mediatrix Press, 2017.

Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition. A Historical Revision, Yale University Press, 1997.

R N Swanson, Religion and Devotion in Europe c.1215-c.1515, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995.

Sonke Neitzel and Harald Welzer, On Fighting, Killing and Dying. Soldaten. The secret World War 2 transcripts of German PoWs, Random House, 2012.

Thanks for this thoughtful essay. I think that when we talk about the normative wrt history, we need always of course, to keep in mind that there are always those who see beyond the norms of their times. Given the religious setting of Bruno's world, let us compare for example, an earlier story in a religious setting- the world of Abraham, in which child sacrifice was fairly common and seen as necessary and righteous. Abraham was fortunate in having no religious authorities standing by to condemn his moment of insight and decision. Thoughts ?

He was tricked into coming to Rome, and you neglected to add that they had cut his tongue out before they tied him to the stake, common practice at the time. There is a place that is named for him on the moon.